Swimming skills are sinking at primary schools

Adam Peaty has brought British swimming back to the centre stage this summer, winning two world titles and breaking his own world records - twice.

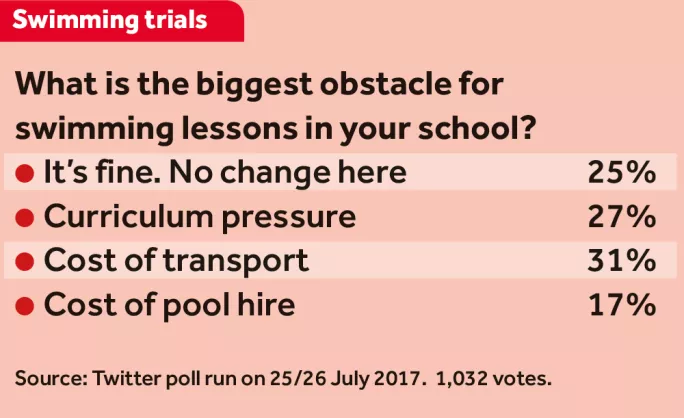

But a snap poll for Tes has found that high costs and time pressures mean that teachers are finding it much harder to help their pupils learn even the basics of swimming.

Of more than 1,000 teachers who responded, only a quarter said that their school had no problems providing swimming lessons for pupils. The rest all cited obstacles - with the cost of transport the most mentioned.

The Twitter poll came after a report from the Curriculum Swimming and Water Safety Review Group found that one in three children leaves primary school without the swimming skills expected for their age.

The group - which includes the Department for Education, sporting organisations and the NAHT heads’ union - also found that around one in 16 schools does not offer swimming at all.

And only a third (36 per cent) ensure all children meet the three national curriculum measures of swimming 25 metres, being able to use a range of strokes and being able to “perform safe self-rescue”.

“We want lots more Adam Peatys, but, actually, the most important thing is to get those basic aquatic skills and be safe in and around water,” Jon Glenn, Swim England’s Learn to Swim and Workforce director, says.

Government support for a national campaign on school swimming and water safety is one of the 16 recommendations in the review group’s report, along with intensive swimming lessons.

Here, we explain why swimming has become a difficult issue for some schools.

What level of swimming are schools required to provide?

The national curriculum states: “All schools must provide swimming instruction in either key stage 1 or key stage 2.

“In particular, pupils should be taught to: swim competently over a distance of at least 25 metres, use a range of strokes effectively and perform safe self-rescue in different situations.”

Swimming is not mentioned in the national curriculum for key stage 3 or 4. The curriculum review group recommends that secondary schools should work with water safety groups, as research shows that teenagers may feel overconfident in the water - 32 young people drowned in 2015, of these 23 were between 15 and 19 years old.

What do schools actually do?

Only about a third of primary schools ensure all children reach all three curriculum goals, the review group reported. It also found that around 6 per cent of schools do not provide swimming lessons at all.

The average time a class is in the pool is 33 minutes and the average number of lessons is 16, the report reveals.

Glenn says: “For some schools, it is too difficult, there is no pool nearby. In some rural areas, it makes sense to be delivered in secondary schools and I’m comfortable with that. But there are schools who say ‘all our children can swim, so we don’t need to deliver it’.

“You wouldn’t say all our children can spell so we won’t do English. Swimming is in the curriculum. It is not a luxury.”

Are schools funded to provide swimming lessons?

As swimming is included in the national curriculum, schools are expected to fund it from their main budget. Most schools with primary-age pupils will receive some PE and sport premium money. This cannot be used to provide national curriculum PE but can be used to develop or add to the activities already offered, which could include enhanced swimming programmes. However, there is no ring-fenced funding.

Is that a problem?

It can be. With school budgets under pressure, headteachers are looking to make savings. And the review found that 18 per cent of primary schools were finding that cost a clear barrier to swimming.

Few schools have their own pools and the cost of transport was the greatest concern for teachers, according to the Twitter poll run by Tes.

Clare Sealy, head of St Matthias CE Primary, in East London, tweeted: “I said curriculum pressure but the cost of pool hire and transport are also a problem. Taken together it’s a real headache.”

The review group report found most primary schools (72 per cent) access public facilities for swimming and the average distance travelled is 2.8 miles.

While some may walk, others need to hire transport. Schools can ask for a voluntary contribution towards the cost of transport. But one respondent on Twitter said that they ask for £24 a term to take children to the local pool, and some parents just won’t pay.

What else stops schools from offering swimming?

Swimming can also take a lot of time out of a school day. Teachers responding to the poll pointed out that travelling to a pool and back can be a big time commitment. In one case, going swimming took all afternoon - including part of lunch - for just a 30 minute lesson.

Other problems cited included a lack of capacity - in some areas, pools have closed, meaning that demand has risen in remaining facilities - and the quality of instructors.

Are there any solutions to these problems?

Schools should be consulted on the proposed closure of local authority pools, according to the report. And schools that have their own pools should be incentivised to expand access to the local community to help them remain viable.

Other options recommended include exploring the use of mobile pools or even safe outdoor swimming opportunities and giving private operators tax breaks to open their pools to schools.

Swim Group - the body with representatives from across the swimming sector that commissioned the review - says it will look into ways of setting up breakfast swim clubs for pupils from more deprived areas and of supporting family swims.

Anything else?

The review also recommends that the government “supports” a new national programme of top-up swimming.

This would see a block of intensive lessons, often held for one hour each day over the course of five days - provided to all children who cannot swim 25 metres by the time they leave primary school.

The review also wants an additional grant to support children in those schools which have been identified as low-performing for swimming. But this money would go to local sports or swimming network, rather than schools.

What will happen now?

There have been positive words, but no sign of any new money.

Responding to the review group’s report, Robert Goodwill, children’s minister, says: “These findings show that more needs to be done to ensure all schools feel confident teaching swimming to students, which is why we will continue to work closely with Swim England and the Swim Group to review the recommendations within this report.”

Sue Wilkinson, Association for Physical Education chief executive, argues that improving swimming skills is not just an issue for government, and requires schools, parents and other agencies to also play a part.

“We all need to pull together,” she says. “Schools are funded to deliver the national curriculum and swimming is a statutory part of the national curriculum for physical education. It is important that accountability measures report on this.”

Glenn recommends that headteachers and teachers take the simple step of paying close attention to what they are getting for their money.

“Schools pay a lot of money for their curriculum swimming,” he says. “They should be checking and challenging what is being taught [in the lessons]. What are they getting for their investment?

“Do the children get rewards and recognition? They are not necessarily asking the same questions as they would do if it was any other curriculum area.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters