Think budgets are tight now? They’re going to get much worse

In 50 years’ time, pensioners in the UK will be receiving nearly twice as much public money as pupils and students, according to latest projections.

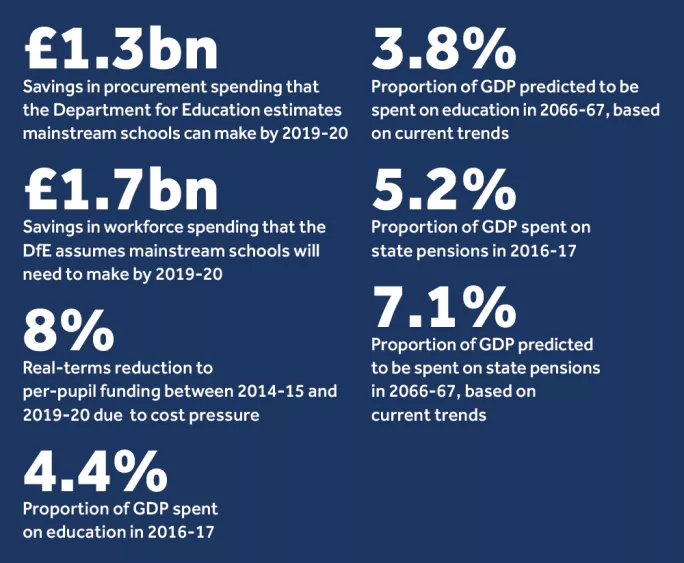

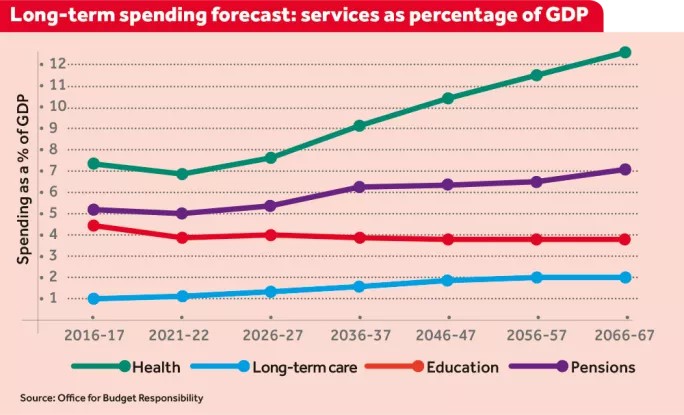

That worrying official forecast for 2067 is the long-term result of a trend - of the old benefiting at the expense of education and the young - already well established in this country. Today, the government spends 18 per cent more on state pensions than it does on education. But the latest projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) show that the gap is set to dramatically widen to 86 per cent.

It is an underlying trend that is unlikely to feature much in the coming weeks as politicians slug it out during general election campaigning - even when the focus is on school funding. But the trend has huge implications for schools, for the teachers who work in them, for our country’s priorities and for the value that we place on our young people.

The generation gap is already stark. Pensioners have benefited from an explosion in property prices and now enjoy higher incomes than working-age adults - while children are today being taught in schools hit by big real-terms cuts.

Former schools minister David Laws says: “It raises the question about whether in our country we’re improving some parts of the education system at the same rate that might be expected in a rich society.”

The generational funding divide has been growing for some time. But fast-forward half a century and education spending in the UK is expected to shrink from its current 4.4 per cent share of gross domestic product to just 3.8 per cent - the lowest proportion since the early 1960s - as more of the national budget is swallowed up by pensions, long-term care and health, according to the OBR.

Early years to suffer

The long-term picture for education spending could spell disaster for schools, according to Laws. “There’s a double risk,” he warns. One likely scenario is “teacher recruitment problems - because salaries will become increasingly uncompetitive”.

The Liberal Democrat, who is also executive chairman of the Education Policy Institute, also fears that the lower share of spending will leave the most underfunded parts of the education sector languishing “because there isn’t any new money coming in and it is very difficult taking money away from established areas”. Early years education is an area that is highly likely to lose out in the funding squeeze, adds Laws.

In other words, not only are we diverting money away from children’s education to fund other priorities, but it is the very youngest who are going to suffer the most.

Laws sees this as posing a major risk to prime minister Theresa May’s pledge to improve social mobility. His fears will resonate with many. It is already the case that early years is funded at less than half the per-pupil rate of primary education, but investing earlier in a child’s life has been shown to narrow the attainment gap more effectively.

While “a lot of politicians are talking about social mobility”, Laws argues that many of the government’s priority policies “are more likely to benefit older people and even working-age adults rather than children, which may mean that less money is filtered through to the people who we really might want to benefit, such as children in their early years of life”. Even the move to provide 30 hours of free childcare is largely about improving the quality of life of working parents, rather than directly helping children, he says.

So how can the government justify squeezing education funding given its vital role it is widely understood to play in improving social mobility? This contradiction is spelt out in research by the Resolution Foundation, published in February, which looks at why the earnings of younger generations seem to be stagnating or falling.

The thinktank finds that this is “likely to be linked to declining relative increases in educational attainment over time”.

Its report says: “The implication is that rapid and consistent improvements in educational attainment have previously delivered a large compositional boost to the pay of each cohort compared to those before, and that a new approach to boosting the quantity and quality of qualifications may be needed to make the same gains in future.”

The report fails to provide any examples of the type of educational improvements that could reverse recent pay trends. And it acknowledges that there are a number of other reasons for these trends, including the growth of zero-hours contracts and part-time hours, as well as greater use of automation.

But the foundation’s executive chair, Lord Willetts, argues that improving the situation would prove challenging without also boosting education spending.

“Children have earned more than their parents for generations, but that has disappeared…due to a slowdown in the increase of educational opportunities,” says the former Conservative minister for universities and skills.

But despite a growing number of school-funding campaigns and the emergence of heads using increasingly emotive language to attack the stark choices they are facing, Willetts fears the funding squeeze is unlikely to be reversed in the foreseeable future.

“The reality is that the political pressures on public spending are very heavily focused on the NHS and pensions - it can be harder to make the case for education spending,” he says.

Tes has previously written about the reasons why the NHS seems to hit headlines more frequently than schools (see bit.ly/SchoolsNHS) and Willetts has his own theory.

“The NHS talks more clearly to our sense of national identity,” he says. “It’s a kind of present we gave ourselves for winning the Second World War. Education doesn’t quite represent that; it’s less distinctive [to Britain].”

The Department for Education’s standard response to concerns about the financial squeeze is to point out that it has protected the core schools budget in real terms since 2010, with funding at its highest level on record. But the National Audit Office has noted that this funding does not sufficiently take account of rising costs and that as a result, schools actually face 8 per cent real-terms cuts between 2015-16 and 2019-20.

Whichever metrics are used, Luke Sibieta, associate director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, is clear about the fact that budgets are being tightened. “Clearly, the amount of spending in education is going down and the number of pupils are going up,” he states.

Effect of deficit

While some schools will be able to make efficiencies, such as by using teaching assistants more effectively, he questions whether there is enough evidence to show that this would create savings of £3 billion - the amount that the DfE believes can be cut through better procurement and more efficient use of staff.

So what does it say about our society that we are prepared to spend more on state benefits for retirees than we are on education? After all, according to Laws, as nations become richer, they generally spend more - not less - on education as a proportion of national spending.

The fact that we are going in the opposite direction, albeit after years of increases - particularly during the Blair government - is partly due to the country’s growing deficit, he says. “But it also raises the question about whether we are improving some parts of the education system at the same rate that might be expected in a rich society, and whether we’re giving enough priority to education,” Laws adds.

This is causing problems for schools in the short term, forcing some to cut staff, shorten teaching hours and narrow the curriculum in order to save money. But the longer-term consequences - reduced social mobility, lower productivity - could be even more severe.

Sibieta says there is little political impetus to address these long-term risks. “Cuts to social care and healthcare are much more visible - there’s an immediate impact,” he says. “Spending cuts in education probably take longer for the impact to be realised.”

If the fall in education spending stores up even bigger problems for the future, then could today’s pupils eventually come to see themselves as the lucky ones?

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters