Troops don’t have to come up with their own battle strategy

In the debate between “traditionalists” and “progressives”, I have always placed myself in the former camp. I signed up happily to at least six of Daisy Christodoulou’s “seven myths about education”, as set out in her book of the same name, and smiled knowingly at Robert Peal’s account of how our education became “progressively worse”. But I have recently become uncomfortable with some accounts of the traditionalist position.

The original argument for a knowledge-based curriculum was that one cannot teach skill without appropriate domain knowledge. This position now seems to have hardened: if we only taught facts, it is sometimes suggested, the skills would look after themselves. Perhaps skill is just an emergent property of factual knowledge; perhaps it is “biologically primary”, a consequence of our genetic inheritance that does not require teaching at all.

But the fact that some skills can be acquired without formal tuition does not show that they depend more than any other on genetic predisposition. It simply shows that our everyday environment is more conducive to learning, say, how to speak than learning how to write or grasp quantum mechanics.

The argument about genetics may be harmful, as well as ill-founded. Educationalists Carol Dweck, Daniel Willingham and Andreas Schleicher all suggest that a belief in innate ability can inhibit learning. Brian Simon has traced the damaging legacy of this belief from the eugenicists of the 1900s through to the psychometric testers of the 1950s and the developmental psychologists of the 1960s.

It has long been observed that factual knowledge is ephemeral, while skills and attitudes endure. It has been said that schoolchildren should not be “engaged so much in acquiring knowledge as in making mental efforts under criticism…you go to a great school not so much for knowledge as for arts and habits” - said in this case not by some firebrand 1960s progressive, but by William Cory, master of Eton College, in the 1860s.

Above all, my discomfort with an excessive emphasis on knowledge is about priorities. Disseminating information is easy; what is difficult is to elicit, sequence, assess and respond to student performance. Doing these things in a continuous dialogue might come naturally to Socrates, conversing with a couple of young aristocrats in the Athenian agora, or to a private tutor, or a don in an Oxbridge tutorial. But for a teacher facing more than 100 children in a day, Robin Alexander’s “dialogic teaching” will appear as a distant dream.

Too often, our response to this difficulty has been to abandon the attempt. Recent government reports recommend that teachers do less marking because there is no evidence that it is effective. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Interventions fail just as often because they are poorly executed as because they are, in principle, the wrong thing to do. Do not give up learning the piano just because you play the piano badly.

In a similar vein, teachers are advised to reduce the amount of feedback they give to students. This argument is based on a simplistic view of what feedback is, a failure to consider the quality of feedback given and a misinterpretation of the work of Robert Bjork. I suspect both recommendations are driven by the need to reduce workload, not by evidence that they would really improve pedagogy.

Nor should we listen to those who criticise “performativity”, whether it is based on the mistaken belief that Carol Dweck deprecates performance (she addresses the mindset in which performance is approached), or on Robert Bjork’s observation that “instructors…frequently misinterpret short-term performance as a guide to long-term learning”.

Far from being a poor guide to learning, performance is our only guide to learning. We cannot cut open our students’ brains and see what knowledge, understanding and skills are inside: it is only by observing performance that we can infer these things. Long-term learning is inferred from multiple performances over extended periods, as it is by such repeated testing and practice that learning is induced in the first place.

Performance is everything. Merely disseminating factual knowledge does not replace the need to elicit, sequence, assess and respond to student performance - and it is our inability to do these things effectively at scale that represents our fundamental challenge.

Systematic pedagogy opposed

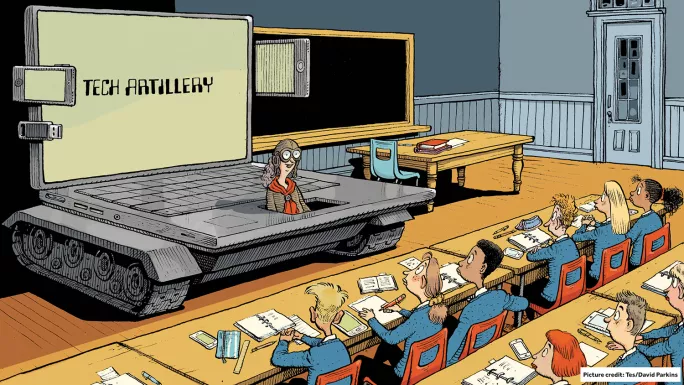

Business meets the challenge of scale by systematising and automating its processes, often with the help of digital technology. There is no reason why education cannot do the same. Many learning interactions are straightforward, predictable and easily automated. More complex activities may still often be initiated with the help of digital technology.

The quality of both sorts of activity would be improved if they were designed centrally, distributed through a competitive market for educational resources and continually optimised in response to usage. The management of spaced practice and personalised remediation, which quickly overwhelms the human teacher, can be handled with relative ease by digital systems. The reliability, validity, fairness and formative value of our assessment system would be transformed if we reduced our dependence on standardised examinations, and based summative judgements instead on data that was aggregated from a wide variety of formative activities. The increased quality and quantity of such data would at the same time transform our research, allowing us to determine with more confidence what good pedagogy looks like.

For all these potential benefits, most teachers oppose systematic pedagogy. They point to previous, unwieldy bureaucratic systems that have increased teachers’ workload to no purpose, promoted simplistic measures of attainment, and undermined teachers’ autonomy and professional status.

The use of digital technology has also been widely discredited: on one hand by mechanistic forms of programmed instruction; on the other, by its association with ultraprogressive pedagogies, which aspired to turn children into independent online learners, and schools into reflections of what was supposed to be the new, libertarian, 21st century zeitgeist.

Again, we should not abandon our attempt to do something well on the grounds that we have in the past done it badly. A doctor’s autonomy, effectiveness and professional status are not undermined, but are rather enhanced by their access to a well-equipped operating theatre. Well-resourced teachers will spend less time in inefficient drudgery and more time doing what the human teacher does best: managing learning, inspiring students, role-modelling behaviours and building responsive dialogues that advance students’ higher-order thinking.

The education theories that go down well on Twitter tend to confirm teachers’ existing inclinations. Aristotle’s theory of phronesis has been cited by several academics to argue that good education depends on the private judgements of teachers about the context-dependent ends of education. They misrepresent Aristotle, who persuasively argues the opposite of the views that are attributed to him.

The explicit definition of our learning objectives, on which the development of any systematic pedagogy depends, is dismissed by Daisy Christodoulou on the grounds that rubrics are simplistic and ambivalent. Yet the original 1987 TGAT Report on national curriculum assessment and testing recommended that learning objectives should be defined by exemplars and not principally by rubrics - a recommendation that still makes sense and which new digital technologies could help us to implement.

Frontline free-for-all

The need to define our educational objectives at all is obscured by the muddled definition of “curriculum” that was promulgated by members of the 2011 expert panel for national curriculum review.

They conflated our learning objectives with the pedagogical means by which we hope to achieve them. When Ofsted urges individual schools to develop better curricula, it is like a military high command ordering individual, frontline platoons each to develop their own strategy for responding to current diplomatic developments in the UN Security Council.

The state of our educational theory and the terminology in which it is expressed are so confused that it becomes difficult even to conceive of systematic responses to our problems.

Teaching is not, in the end, about the dissemination of information. It is a conversation, an iteration of performance and feedback. This conversation becomes unmanageable as education is scaled to meet modern demands.

While the student’s ultimate interlocutor still needs to be a human teacher, many routine interactions and processes can be automated and replicated consistently. Our educational discourse has been conditioned by past failures into thinking that such systematic approaches are impossible. Teachers have become expert, not in addressing fundamental educational problems, but in coping within a dysfunctional system, whose theoretical foundations are themselves rarely questioned.

It is time that we re-examined our assumptions, clarified our terminology and looked for more imaginative solutions to the fundamental problems that we face.

Crispin Weston is an edtech consultant and tweets @crispinweston

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters