‘The true scale of the problem is now exposed’

For years, budgets for pupils with high needs have been heavily propped up with money taken from local authorities’ main school funding pot.

But, as previously highlighted by Tes, this is set to be restricted under new rules being brought in from next year as part of the national funding formula for schools.

Under the new system, which will come into effect from next April, local authorities will need permission from the education secretary if they wish to use more than 0.5 per cent of their general school funds for high-needs pupils.

Now, Tes understands, even this limited flexibility may be shortlived. School funding expert Julie Cordiner says the Department for Education has “indicated that this flexibility will probably be withdrawn from 2019-20”.

Cordiner recently attended a DfE funding workshop, held in the north of England, where a departmental official said the DfE is “minded” not to allow transfers of the schools block after 2019-20.

If borne out, the change could have a dramatic impact on high-needs provision in schools. According to the NAHT headteachers’ union, people are already panicking at the prospect of the 0.5 per cent limit.

The union says that the change will leave many councils with three options: using up their reserves, going further into debt, or cutting services.

Valentine Mulholland, the NAHT’s head of policy, says: “The true scale of the shortfall in high-needs funding has been partly masked in recent years by local authorities making up the shortfall from the schools block, but as this will no longer be possible, the true scale of the problem is now exposed”.

She adds: “That half a per cent is bringing to light how serious the high needs funding crisis is. People are really panicking about it”.

The NAHT is working with the Local Government Association, which represents councils, to tackle the high-needs funding shortfall, including coming up with an estimate of what is needed to properly fund this area.

Mulholland adds that, while the new formula is a “sensible approach” in terms of assessing the relative needs of councils, “we need more high needs funding - and we’re seeing that this year, as local authorities are desperately trying to deal with the deficits they’ve got in high needs”.

‘Children could miss out’

Another problem posed by the new funding system is the length of time that councils will have to wait to get the budget increases they are due.

Some local authorities that should be getting between 10 to 20 per cent more high-needs funding based on the formula will only receive a fraction of that in the short-term, because of the 3 per cent cap on any increase in one year. This means they face waiting years to get the total amount owed.

Richard Watts, chair of the LGA’s children and young people board, says that without extra funding “councils may not be able to meet their statutory duties and children with high needs or disabilities could miss out on a mainstream education”.

There also appears to be a risk that high needs funding increases are not being targeted at the right areas.

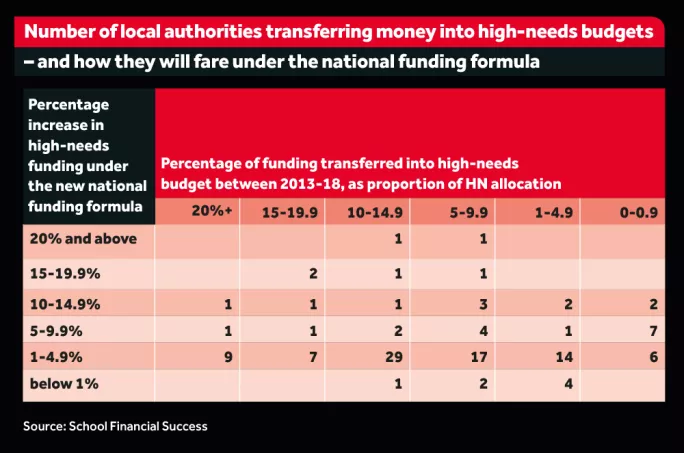

Cordiner, a former member of the DfE’s School Funding Implementation Group, has carried out new research which, she says, shows the extra money being provided under the funding formula is being allocated in a “random” way.

Most councils that have had to transfer funds worth 20 per cent or more of their high-needs income will receive a funding increase of less than 5 per cent under the new formula, according to Cordiner’s research, published in a blog at schoolfinancialsuccess.com.

However, the research makes “some very wild assumptions”, according to Mulholland.

“I don’t think you can make an assumption about who has the greatest need based on who’s been spending the most money,” she adds.

She says there are “enormous variations in how local authorities allocate high-needs top-up funding, with variations from £1,600 per pupil per year to over £19,000”.

Another prominent figure who has concerns about the new system is Kevin Courtney, the joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union.

He says: “The national funding formula for high needs is not based on an accurate assessment of the real and growing costs of high-needs provision.

“It will further restrict local authorities’ ability to support this vital area from other funding and will make the problems facing many schools even worse”.

He adds: “It’s obvious that what is needed is more funding overall for high needs, based on a comprehensive and objective assessment of those needs”.

The DfE was approached for comment.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters