Is the UTCs programme on ‘pause’?

If royal approval were all the university technical college (UTC) movement needed to succeed, its future would be secure.

Speaking at an awards ceremony at St James’s Palace this month, the Duke of York said UTCs probably offered “the most useful basis of knowledge in any school system that we have in the UK” (bit.ly/YorkUTCs).

For him, the institutions for 14- to 19-year-olds that combine academic subjects with vocational education and technical training provide the greatest flexibility to cope with the “velocity of change” in the workplace.

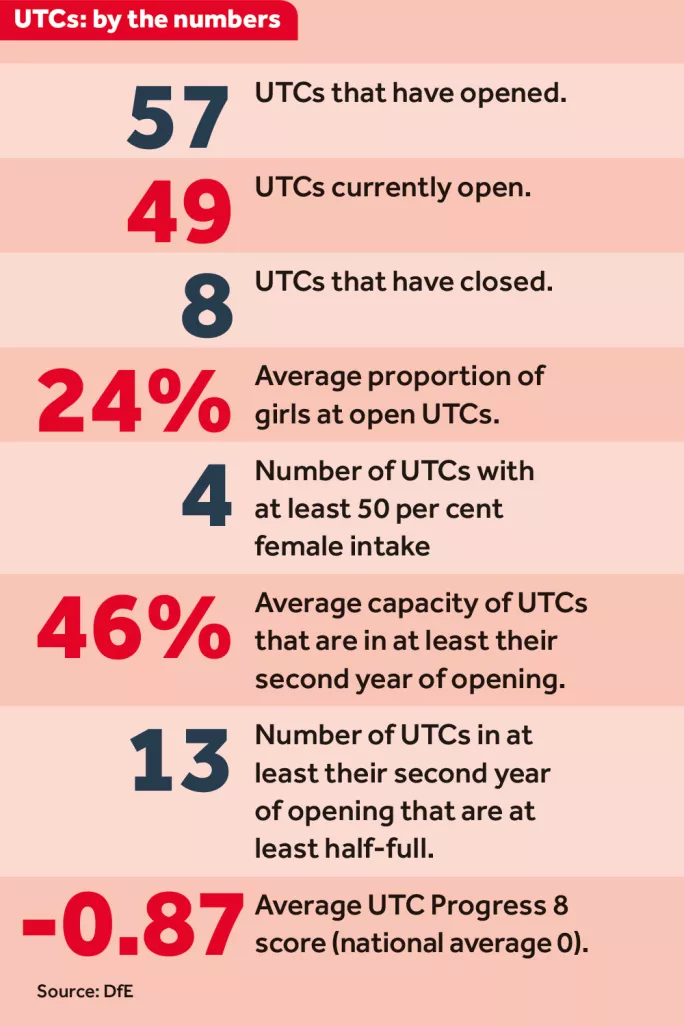

But while Prince Andrew may have voiced his support for this relative upstart on England’s educational scene, the government seems less convinced. According to Department for Education data released this week, out of 302 new free schools currently in the pipeline, only one is a UTC: North East Futures UTC, in Newcastle.

‘Restart the machine’

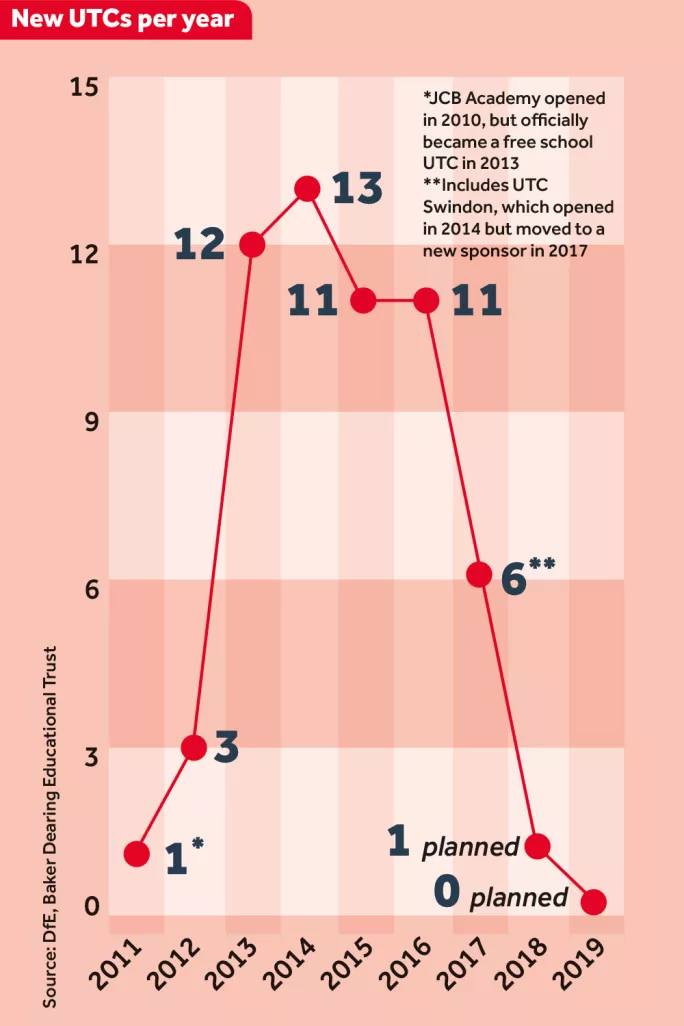

Between 2013 and 2016, the number of new university technical colleges opening annually ran into double digits, but this September only five were created, while just one is due to come into existence in 2018.

And none are due after that, according to Charles Parker, chief executive of the Baker Dearing Educational Trust, which promotes, licenses and supports UTCs.

He says it takes three years to develop a UTC. So has the government, in effect, put the programme on pause? Parker thinks so.

“Justine Greening has said that UTCs are a great example of partnership working between business and education, so what we need to do is to persuade the secretary of state, who has been very helpful compared with her predecessors, to restart the machine,” he explains.

Parker describes the years since the first UTC opened in 2010 as “tough”. That may be an understatement.

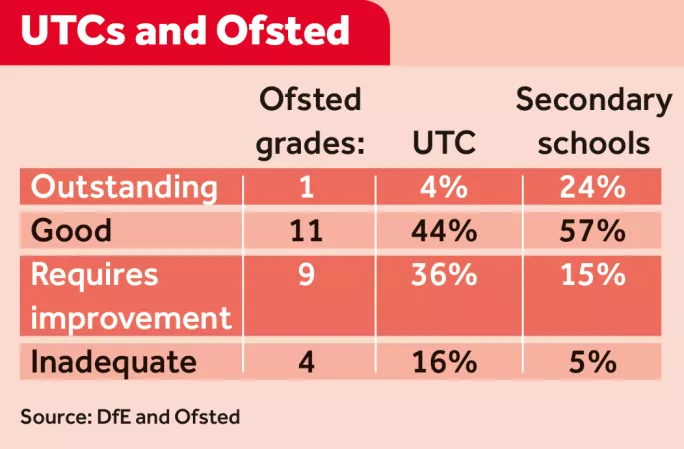

The institutions, championed by Thatcher-era education secretary Lord Baker and enjoying cross-party support in 2010, have been bedevilled by closures, poor recruitment, negative Ofsted verdicts, disappointing GCSE results and a stark gender imbalance.

Shadow education secretary Angela Rayner has dismissed UTCs as “vanity projects that just don’t work”, calling for ministers to invest instead in existing colleges.

Mary Bousted, joint general secretary of the National Education Union, says that recruitment failures and poor Ofsted judgements mean UTCs are “not fulfilling their promise”, but adds that this “does not mean they are a bad idea”.

“I think they were set up too quickly, without sufficient thought, which means too many of them are ‘requires improvement’ or in special measures,” she says.

But, for Parker, the problems simply show “how difficult it is to introduce real change in an education system which really does not like change - and does not like disruptors, which is what we are.”

The UTC closures have, in the main, been blamed on their failure to attract enough pupils. Recruitment was always likely to be a challenge for institutions that have to tempt young people, and the funding that goes with them, from existing schools at the age of 14.

The latter had little incentive to cooperate, unless, as former education secretary Michael Gove claimed, they saw an opportunity to offload underperforming children.

It was Gove’s DfE that introduced UTCs. Now he describes them as a “cherished idea [that] has all gone Pete Tong”.

Recruitment is an area where the government has taken action, telling councils in February that they must write to the parents of 13-year-olds with information about any nearby schools that admit pupils at 14. Three months later, Parker said applications for Year 10 entry to UTCs were running at double the rate of the same time last year.

But instead of addressing the information gap, would addressing the age range itself be more effective?

An age-old question

In May, a report from the IPPR thinktank concluded there was “insufficient evidence to demonstrate that transition at 14 is advantageous to pupils with an interest in pursuing qualifications in technical subjects”.

Its authors called for UTCs to instead become “high-quality providers of technical education for students aged 16-19”, with only those that had positive Ofsted ratings and good pupil outcomes allowed to continue recruiting at Year 10.

It is a suggestion that Parker rejects, saying “the biggest thing that distinguishes us is the fact that we absolutely insist on educating children in key stage 4 and 5”.

But there is another option already being put into practice that goes in the opposite direction: recruiting at an earlier age.

Next September, UTC Sheffield will become one of the first to accept Year 9 pupils for an extended three-year KS4, and the effects appear positive. Across its two campuses, it has received 295 applications for the 200 Year 9 places available in 2018. It is not, Parker thinks, a blanket solution, but “we encourage it where it works in the local landscape”.

Another reason UTCs have been under pressure has been a perception that they are not performing well. But are the headline measures that lead to this conclusion simply biased against UTCs? As institutions that are very different to traditional secondary schools, is it fair to hold them to the same measures?

In June, the National Foundation for Educational Research highlighted a “mismatch” between the UTC curriculum, which is designed to be 60 per cent academic and 40 per cent technical, and Progress 8, which only allows 30 per cent credit for technical and vocational qualifications.

And it noted how headline accountability measures fail to capture some of the very outcomes UTCs were set up to deliver, such as employer engagement and the destinations students progress to. On the latter, the researchers say initial self-reported data “suggests promising outcomes”.

Play or pause?

Although there are now almost 50 UTCs across the country, the future of the programme remains very much in play.

Many feel that, despite the problems some UTCs have encountered, there is a place for them in the education system. Bousted says: “When Kenneth Baker says we need people to do programming more than getting an F in French, he is making a really important point. The current EBacc curriculum is simply inappropriate for a wide range of pupils.” However, they face significant hurdles, she adds. “The UTCs have an important place, but at the moment, the odds are against them to succeed.”

Charles Parker’s organisation audited the remaining UTCs following the recent closures. Some were small and some had financial difficulties, he says, but “what was going on in all of them educationally was very good, so we decided we were not going to close any more for a very long time”.

Unless this bold promise holds true, it could be some time before the “pause” is lifted.

The DfE was contacted for comment.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters