What’s the point of spending hours and hours marking?

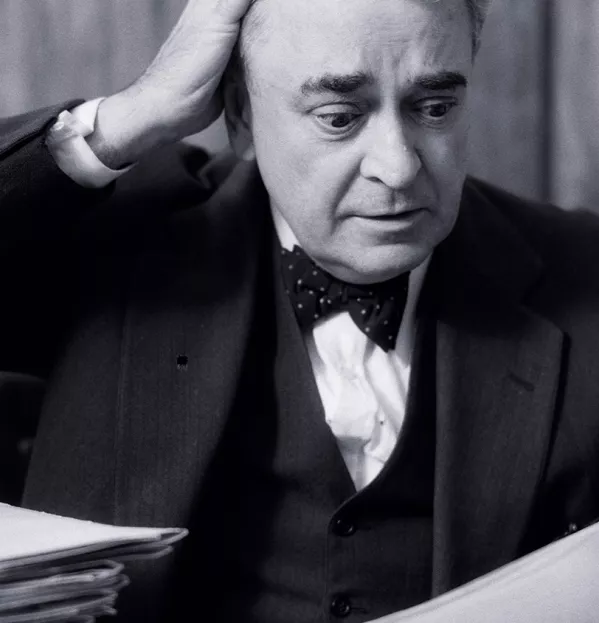

It has probably been true for much of my teaching career, but I rarely get a more sick feeling in my stomach than when I have pile of marking in front of me - especially on a Sunday night - and I’m convinced that much of my feedback will be ignored. I’m scared to think of the time I’ve wasted. And it is all done with the best of intentions, of course. We all want our classes to know that we care, to know that we read their work and want them to improve. It just seems like there is a disconnect between what we feed back and what they learn from that.

For years, I made a point of reading everything my pupils wrote. Until the last year or two, I still did that. I have doubts that much of the time I spent on correcting errors had much of an impact, however. I look through the pupils’ work for the year and I see the same errors occurring. Our much-heralded correction code - in every homework diary - was meant to sort all of that, but it doesn’t. So what is feedback for? Well, according to the educationalist Dylan Wiliam, we should focus less on improving the piece of work we are marking and think more of the next piece; in effect, we change the person, not the work.

Cut your workload

Teachers need to get out of the habit of writing excess comments on pupils’ work. It rarely has the impact we desire. So why do we continue to do it? For our own peace of mind? For parents? For management? Perhaps. But I get the feeling that much of it has to do with ego.

We want pupils to think we care; we want parents to think we are helpful and supportive; we want our leadership team to believe we are on top of things - all laudable. We’re probably mistaken, though. If we are to address our increasingly untenable workload, and with it the disconnect between the feedback we give and the feedback pupils receive, we need to take ego out of the equation.

I do it all the time. I write positive, encouraging comments because I want them to like me. I make a big deal of a good, impressive total in a test because I want them to like me. I overuse praise because I want them to like me. We make a show of handing back work when we’ve spent so much time on it because, deep down, we derive some praise in return. Feedback doesn’t work like that. Feedback like that doesn’t work.

So we need to find ways to help pupils to engage with their feedback; to challenge them to focus on what they need to do to improve and to build on those areas. Surely this is what we mean by active learning. It doesn’t mean that they have to be moving about and outwardly active; it means they have to be actively involved in their own improvement, gradually becoming less reliant on the teacher as they move on to their next stage. And there are ways to do that and, in turn, to begin to alleviate our own workload.

When I have sets of work to mark, I’ve started whole-class feedback. I sit with a piece of paper, or a specially created feedback form, and read through the pile of jotters. I look for misconceptions and common errors and jot those down. If these are consistently coming up then it is clear that I have not taught them properly and so need to try again. The next lesson is then used for reteaching those points. Then pupils have to redo the work. Simple. I cut my marking time from about three hours for a set of essays to about one hour. I have also stopped adding up marks in a practice paper, even though I find it strangely pleasurable. When you pass them to pupils, what is the first thing they do? Add the marks up, trying to catch you out. They then ask their friends what they got, rendering any written feedback meaningless.

Engaging feedback

Let them do it; save yourself time. Writing a grade or number ends the learning for that piece. Let them add it up and move on to the important stuff. Mark it in such a way that they have to wander around the room, looking for someone who got a better mark for that question. “Why is it better than mine? What is the difference between your answer and my answer?” That’s when the real learning starts.

I’ve waited for too long to expect someone to come along and magically reduce my workload: it ain’t gonna happen. Why would they? So, in order to preserve my sanity and to stop the descent into exhaustion, I have made some radical changes to my marking approaches. Time has been freed up to prepare better lessons, and I am also able to stop working on the odd Sunday or, dare I say it, midweek evening.

Marking less to feed back more might just be beneficial for everyone in schools.

Kenny Pieper is a teacher of English in Scotland

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters