Who pays for a safety net when no one is falling?

After years of gradual local authority decline, schools have, to varying degrees, got used to life without any dynamic support or ownership from their LA. Instead, professional nourishment is now found elsewhere. So, how significant is the disappearance of your LA as standard-bearer or system coordinator? And what is now keeping schools from crisis when a perfect storm hits them?

Since the days of absolute centralised control, schools have steadily been liberated and, of course, we have gained from our new freedoms. There have been some remarkable examples of transformation, as brave and innovative leaders have extended their influence over failing schools, and some multi-academy trusts (MATs) or teaching schools have become effective servants and enablers of the weak.

Conversely, we have seen less positive behaviours from some of these newly liberated school leaders. A competitive world of high stakes has fuelled less-attractive behaviours and rewarded skilful politicians who are making sure their own institutions or businesses thrive through ever-expanding levels of influence and control. Who has the authority to check this powerful cadre of “system leaders” when LAs have been so reduced in capacity and resource?

Of course, the general culture of collaborative school working is a pragmatic blend of cooperation and competition, and most system leaders have to juggle shrewd self-interest with a genuine sense of responsibility that goes beyond their own gates. The question is, which way are we heading if the system keeps generating these less-helpful behaviours?

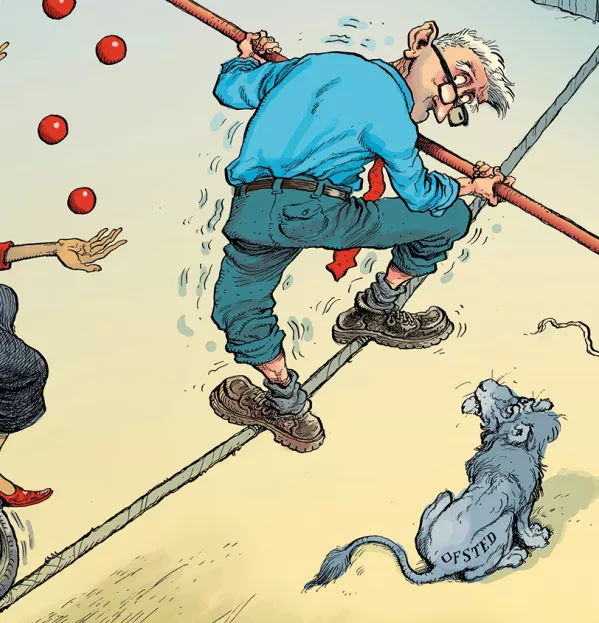

And if LAs have gone, have our problems gone, too? One might imagine the high-wire trapeze artist not noticing a change in arrangements until the day they fall and find the safety net has gone. Or a well-practiced orchestra not noticing that their music was deteriorating after the conductor left. Or perhaps the problem is not the risk of failure or the need for more support, but the absence of scrutiny over excessive self-interest and the personal power of a new elite.

With the majority of maintained schools still not academised, many heads will want a focus for belonging and support. Many stand-alone converter academies are more acutely aware of the seriousness of “business” risks that they must mitigate in their independence, while the leaders of teaching schools and MATs can also be challenged by how they can match the wider needs and opportunities of the system with their own offer.

Localised response

Up and down the country, something really interesting is happening. As LAs diminish, not through design or policy, a patchwork of organisations is appearing, as different parties respond to local need:

- In Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire some time ago, LAs supported the establishment of new entities to take over many of their duties.

- In Sheffield, Liverpool and Manchester, the focus has been more discretely on school improvement or leadership development alongside particular elements of a city’s relationship with its schools.

- In Essex and some London boroughs, heads have organised themselves into a local self-help and support function.

- In Birmingham, where more secondary places are needed, we have just seen one flagship secondary academy go through a journey of special measures, a financial notice to improve, and traumatic and expensive closure.

There are other schools that have been stuck for more than two years of special measures with academy orders, where sponsors steer clear or try bargaining and brinkmanship, as they seek the best possible deal from London. In these settings, as well as a whole host of schools in tough neighbourhoods that have struggled for years to remain securely good, the market is not enough. Despite the need, none of these new groups is guaranteed funding or recognition in the system; they are living from hand to mouth.

Without some mechanism for gathering local intelligence and coordination of the capacity across all schools, the new bid-dependent Strategic School Improvement Fund is an incomplete answer.

The problem is that there is no appetite from anyone to fund or empower these new “middle tier” organisations and there is a leap of faith being made by ministers who hope that the market will save them from paying for this work. The ideal across the country is that schools lead and own these organisations, but making strong and meaningful relationships across a MAT of five is tough enough; a partnership of 300 or 400 becomes a distant and low priority for heads.

When the Birmingham Education Partnership took on the formal school-improvement duties from the city council, large and charged with important system functions, heads struggled to see the partnership as their own. And because more trapeze artists are not falling to the ground, when money is scarce, paying for the safety net is a low priority.

These post-LA organisations could be the local peacekeeper when different interests clash, as one school unilaterally takes an extra class from an improving but less shiny neighbour. They hope they can mitigate against the vulnerabilities created in a marketplace in which the weaker, poorer schools serve the most vulnerable families and struggle for capacity to recruit and improve.

In a city of social and ethnic division, perhaps the biggest challenge is in trying to help individual schools and small MATs to not just hunker down in one small patch, but to stay connected, relating strongly to a range of partners, to the whole city with its very different neighbourhoods.

Don’t leave it to luck

To any politician or economist, I would argue that the cost of school failure is too great. It makes sense to have a safety net before a crash landing with Ofsted.

To anyone who has had several headships, and experienced the huge variability and significance that comes from very different local communities of professional support, it seems absolutely vital that we work nationally to ensure all schools have a guarantee of systematic high-quality peer support. Having supportive networks and helpful partners is simply too important to be a matter of luck.

Given the universal agreement among all parties that cycles of poverty must be broken, as our economy depends on a high-skilled workforce, for the sake of children in poorer and more vulnerable settings, and in the free market of weak and strong schools, we have to invest systemically in ways to protect against the strong always having the advantage.

Our new middle-tier partnerships can provide some potent and far-reaching answers; they need to be understood and supported.

Tim Boyes is chief executive of the Birmingham Education Partnership and a former headteacher

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters