Why academy chains mean the death of the superhead

“The traditional image of the charismatic, omniscient, omnipresent heroic leader is no longer viable.”

So said the ATL teaching union in 2014, as it examined the changing role of headteachers with an increasing number of schools joining multi academy trusts (MATs).

Fast-forward three years and it is clear this trend is here to stay.

With MATs an ever more central part of the school system, what has become of the once all-powerful school leaders - so-called “superheads” - now that they have to answer to an executive head and chief executive above them?

A report published today suggests it means, at the very least, less job security for the school leader. The study on headteacher retention from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) reveals that schools in large MATs were less likely to retain their heads over a three year period than schools that were not in MATs (bit.ly/NFERheads).

And some heads interviewed for research said they were “concerned about a wider loss of professional autonomy associated with working in a MAT”.

Not leaders, but managers

Mark Wright, the director of the Association of Managers in Education (Amie) section of ATL, is concerned about how the school leader’s job is changing.

For him, good heads who were trusted by their council and had their governors on board were “all-mighty, all-powerful”. But this is not the case once they have been subsumed into an academy chain.

“They should not be called school leaders, but school managers. That’s the difference. The CEOs have the power,” he says.

“When the government talks about increasing freedom and flexibility, it only went to the very top. The executive heads and CEOs have kept that power, and in a way it means those below have become managers of what the top people say they have to do.”

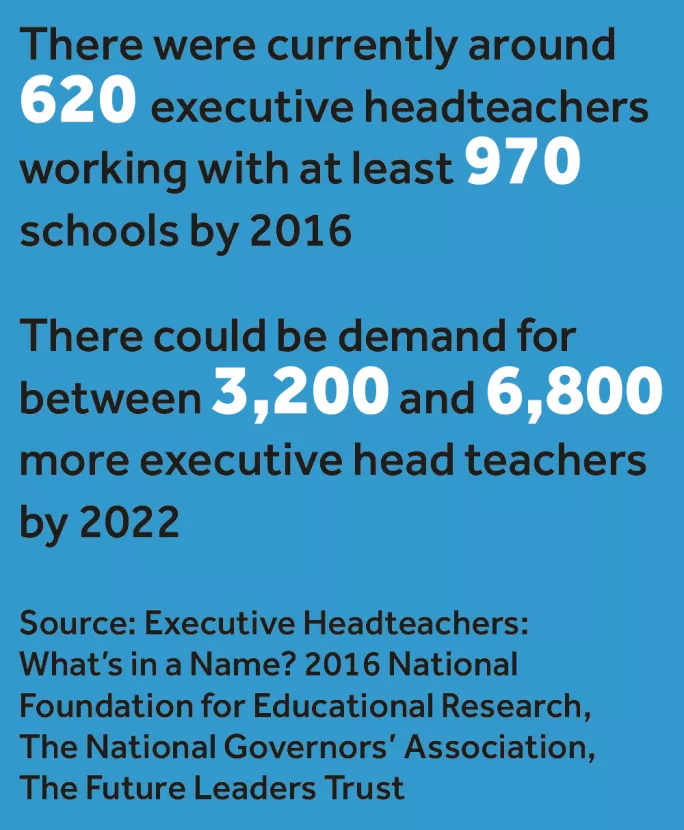

Last summer, a report by the NFER, the National Governors’ Association and The Future Leaders Trust highlighted this growing new tier above the traditional headteacher.

Then, there were 620 executive heads - a 240 per cent rise since 2010. The authors estimated there may need to be between 3,200 and 6,800 more by 2022.

The increase is driven not just by the rise in the number of the academy trusts, but also federations of schools, and the authors called for further research on the relationships between headteachers and executive heads.

The autonomy of individual heads of school varies among different academy chains. Some have flexibility as long as they hold true to the trust’s core values. Reach2, the largest primary-only academy trust in England, says on its website that “it is very important that each school has the opportunity and the freedom to respond to the needs of parents and children and create their own local solutions”.

In other MATs, schools gain “earned autonomy”. The University of Chichester Academy Trust says it “delegates significant functions to academies that are performing well and only a few to those academies that need greater support”.

But the leaders of some of the most prominent academy trusts have been explicit about the reduced role heads of schools play.

Ian Comfort, the former chief executive of the Academies Enterprise Trust, has noted that heads of maintained schools have more autonomy than those in MAT academies, who have to “give up their sovereignty” when their school joins a chain.

‘We run it like one big school’

And Sir Michael Wilkins, the founding chief executive of the Outwood Grange Academies Trust, has said: “We run it like one big school. Principals are more like heads of departments.”

It is a model that can have benefits, both for the headteacher and the academy trust.

Many MATs take on back office functions, saving money through economies of scale and standardising practices across their academies. For heads, this can mean a release from administrative tasks, allowing them to focus on teaching and learning.

But in some trusts, a headteacher’s autonomy over areas such as the curriculum and teaching is also removed and given to the centre.

Malcolm Trobe, deputy general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says: “One of the things we are picking up is that there are occasions a set model of doing things is set from the top, and the head of school more or less becomes an implementer of this approach.”

For schools that are in difficulties, that can be “very justified”, he believes. But it is a question of balance between the trust and the school, as well as the different skills that key people have. And sometimes, a headteacher may want their school to join an academy trust believing that they will retain a large degree of autonomy - only to find things work out differently once the school is locked in.

Trobe says: “That’s a story that we have heard on a few occasions, where people have signed up for a trust believing they would have signed up for one thing.

“Over a period of time, they find that the MAT is imposing a different way of working which effectively means less autonomy.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters