Would you wear a bodycam?

You’re midway through a lesson when suddenly one of your pupils kicks off. It starts as a verbal barrage, then it escalates into violence. You manage to defuse the situation, then later you call the parents in for a meeting.

Your version of events differs from the pupil’s. The parents side with their child. They don’t believe you. They don’t believe it could be as bad as you claim. They get up to leave.

So far, so depressingly familiar for many teachers. But what if, at that moment, you could show them what really happened? What if, rather than yet another meeting ending in frustration, you could sit everyone down in front of a computer screen, hit a button and play back footage of the incident that you captured on a camera mounted on your lapel?

There, clear for all to see, is what happened. There ends the debate.

There is the proof that turns endless wrangling over “who said what, when” into “what happens next?”

Could this scenario, and others like it, ever become a reality in UK schools?

Wearable cameras have worked to great effect to reduce antisocial behaviour during trials by UK and US police forces. There have also been instances in the US of schools adopting the technology in the classroom.

Meanwhile, behaviour in UK schools is consistently reported to be deteriorating. In 2015, four out of 10 teachers experienced violence from pupils, according to a survey conducted by the ATL teaching union.

Of the panel of 1,250 teachers questioned by the union across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 45 per cent stated their belief that pupil behaviour had worsened in the previous two-year period (2014-15).

Support staff have also reported problems: in June last year, Unison released figures that showed 53 per cent of classroom or teaching assistants had experienced physical violence at school in the past year.

As uncomfortable as it may be for a profession that prides itself on trust and relationships, is it time we gave a more radical solution - like teachers wearing cameras - a try?

As controversial as the proposal might be, evidence suggests that the wearing of “bodycams” can have a significant effect on how people behave when dealing with authority figures.

A study published by the University of Cambridge last year, which looked at how people behaved when they interacted with police officers wearing bodycams in the UK and US, found that the cameras had a positive effect on both the officer wearing them and the members of the public that the officer interacted with.

Complaints against officers fell by 93 per cent over a 12-month period compared with the previous year, with researchers suggesting this was the result of both parties adjusting their behaviour. They pointed out that the most beneficial effects were noted when officers recorded entire encounters and notified the public that the camera was running as a “digital witness”.

Dr Barak Ariel from the Cambridge Institute of Criminology, who led the research, said: “Once [the public] are aware they are being recorded, once they know that everything they do is caught on tape, they’ll undoubtedly change their behaviour because they don’t want to get into trouble.

“The cameras create an equilibrium between the account of the officer and the account of the suspect about the same event - increasing accountability on both sides.”

Life through a lens

You can see how a similar outcome might be achieved in schools, but taking the findings of this study and applying it to the classroom without a clear rationale would be a risky strategy, says Dr Alex Sutherland, research leader for communities, safety and justice at RAND Europe, who co-authored the University of Cambridge report.

Sutherland feels that a raft of questions would need to be addressed before bodycams could be worn by teachers in UK classrooms, the most important of which would be: what problems are the cameras supposed to help with?

“My concern is that copycat behaviour and basic social influence - ‘Hey, they’ve got cameras, we should also use them’ - might be driving those schools asking about using cameras, [rather than them] having a clear justification for doing so,” says Sutherland.

“With the police, the reason for using them is clear: the police interact with the public and are legitimised by the state to use force against, arrest and detain citizens. There is a lot of evidence on how well or badly these interactions can go. What is the rationale for using them in schools?”

But Tom Ellis, principal lecturer in the Institute of Criminal Justice Studies at Portsmouth University, is more optimistic about education applications for the technology. He completed a study of a blanket roll-out of body-worn cameras to all front-line officers on the Isle of Wight and says that the key to success would be proper implementation.

“It is a question of communication, implementation, training and leadership,” he explains. “Our study suggested that you can’t just hand out cameras and expect them to work if the technology is all ready to go, but you haven’t had meetings, forums or demonstrations to explain their purpose to both staff and, in this case, students. It will be crucial that parents are also included.

“We [also] found that all officers needed to be issued with cameras, rather than allowing optional use, or only handing it out to certain officers. This normalises camera use more quickly. Officers who had not used the cameras were more likely to be negative about their introduction than those who had.”

Despite Ellis’ view that education could embrace bodycams, real-world examples of cameras in schools are few and far between. But in the US, some schools have already taken, or looked to take, the plunge.

In spring last year, principals and assistant principals at Halifax County High School and Middle School in South Boston, Virginia, started wearing bodycams donated by the local police department.

Michael Lewis, principal of the school, says that over the past few years, students have become more accustomed to being recorded thanks to the onset of social media and smartphones. As a result, they have not “altered their day-to-day behaviour based on the [school staff] wearing these cameras”.

While we do ‘police’ behaviour and learning, we are not the learning police

What the cameras have done, though, is provide useful evidence for when school rules have been broken.

“The cameras have certainly helped with management within our schools,” Lewis explains. “Fortunately, we have only had to use them a few times to actually record conduct that is in violation of school policy.”

The cameras have been viewed as useful and workable in the school environment, and the benefits seem clear. So is it just a matter of time before a UK head follows Lewis’ lead?

The trouble with bodycams

If the reaction of the teaching unions to CCTV in the classroom is anything to go by, then there will certainly be challenges to any school that attempts to trial bodycams. The presence of cameras in some classrooms was the subject of a major NASUWT campaign in 2012, after a survey it conducted found that 8 per cent of teachers had a CCTV camera in their classroom. The union heavily criticised the practice as a violation of professional privacy; going further and putting the cameras on every member of staff would be greeted with a similar reaction, says Chris Keates, general secretary of the NASUWT teaching union.

“This is a proposal that is fraught with difficulty, not least in relation to safeguarding pupils, and also the safety and security of staff,” she says. “If the purpose of wearing bodycams is to tackle discipline, then using a camera in and of itself doesn’t prevent violent or poor pupil behaviour. Similarly, if the practice is for the purposes of supporting school improvement, you don’t need a camera for teachers to be able to realise when pupils are engaged or disengaged in their learning.”

The ATL teaching union is even more adamant that such a development would not be welcomed.

“All schools should be safe places for pupils and staff,” says Dr Mary Bousted, general secretary of the ATL. “All the evidence suggests that the best way to ensure children behave well in schools is for schools to have a good behaviour policy, which is accepted by all staff and parents, and is consistently applied in the school with sanctions that all pupils understand. If schools have good behaviour policies, they shouldn’t have to resort to using body cameras or CCTV.

“We would not support schools being turned into prisons.”

It is a stance that you would expect teachers to share. The evidence suggests that one of the key factors in a student’s learning is the relationship they strike up with teachers, so teaching staff in UK schools tend to place a high value on the power of clear boundaries, trust and consistent enforcement of rules. A camera would arguably break that trust and potentially damage the student-teacher relationship.

A senior comprehensive school teacher based in Romford certainly holds that view.

“I’m not sure parents would be keen and the unions definitely wouldn’t be,” says the teacher. “I’m suspicious that it could be used in another way: by the school against staff.”

Amy Forrester, a teacher at Cockermouth School in Cumbria, also has reservations. She thinks schools would have to exhibit extreme caution before going down this route.

“The police have a very different role in the world than teachers,” she says. “I would hate the development of teachers being turned into the police. While we do ‘police’ behaviour and learning, we are not the learning police.”

Yet, Ellis suggests that there are UK schools that have already begun to implement body-worn cameras. Through his industry sources, he knows there are at least two that are at an early stage of implementing the technology - he says that neither are willing to talk about the development until they are further along in the process.

Meanwhile, Ewan Christie of Body Worn Video Systems UK says that he knows of a couple of instances where his cameras have ended up in the education sector.

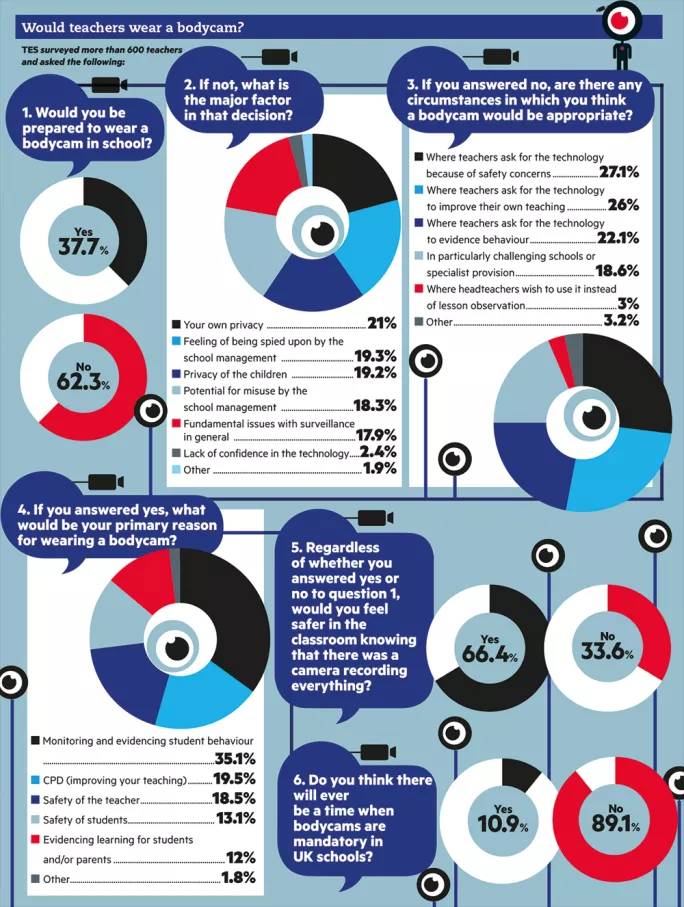

And it seems that teachers may be more willing to embrace cameras than might have been expected. A TES survey has found that, of the more than 600 teachers who took part in the survey, 37.7 per cent said that they would be prepared to wear a bodycam in school.

In addition, regardless of whether or not they would be prepared to wear a camera, the majority of respondents - two-thirds - said they would feel safer in the classroom knowing that there was a camera recording everything.

It’s clear that a number of teachers have concerns about classroom safety and believe the introduction of video monitoring would be worth considering.

“I’ve witnessed countless physical assaults as a teacher and I have been physically assaulted while teaching on a number of occasions,” says teacher, education writer and TES columnist Tom Starkey. “I am unsure that a bodycam would have acted as a deterrent, but it would have been an easy way to evidence these assaults, removing any ambiguity of reported events - or spurious claims - on any side, and it might have gone some way to reducing the paperwork that is linked to such unpleasant occurrences.”

A maths teacher in a Hampshire secondary, who wishes to remain anonymous, agrees.

“I would have no problem with it,” they explain. “The kids are so used to being filmed that they would not have an issue with it, and it would be there - and I would explain this - to protect them as much as me.

“If a student is bullying another, or an assault occurs between students or towards me, then there is video. If a child persistently disrupts others, there is video. If they think I have behaved badly, then there’s video and I am accountable. I don’t fear that. I would rather there be video to defend myself against that accusation - and if there is truth in it, at least I can see how I came across and adapt my behaviour.

“We don’t have enough time as it is in schools - a camera would streamline the processes and ensure that we can sort out problems quickly. I do believe that it would eventually change behaviour for the better. What do those opposing [the idea] really fear?”

Candid cameras

One worry identified by respondents to the TES survey is being spied upon by management and/or the potential misuse of cameras by school leaders. Another issue that teachers opposed to the wearing of cameras identified is privacy - both for themselves and of children.

The latter issue has already caused one school district in the US to abort plans to introduce bodycams. In 2015, the Burlington Community School District in Iowa investigated the possibility of fitting cameras to principals and assistant principals to provide additional video and audio documentation to the surveillance cameras already in place at the school.

However, Jeremy Tabor, director of human resources at the Burlington Community School District, says that the plans were eventually shelved, because the district wanted to maintain “strict compliance” with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) rules and guidelines.

A camera would ensure we can sort out problems quickly

As is the case in the US, UK schools would need to get to grips with compliance issues before they could roll out the cameras, according to Matthew Wolton, partner at Knights Professional Services.

“In order to use bodycams, the school would need to be able to process personal data under the Data Protection Act,” explains Wolton. But he adds that this particular hurdle could fairly easily be overcome by making it a condition of entering school premises. Individuals wearing the cameras would need to undergo appropriate training. But the bigger issue would be security of the footage because if it became publicly available, the school would get into a lot of trouble, he warns.

Interestingly, these privacy concerns and the aforementioned “spying” fears have been handled without much hassle when schools have adapted classroom monitoring software, such as IRIS Connect cameras, which sit in classrooms and record lessons for CPD purposes.

Graham Newell, director of education at IRIS Connect, explains that teachers are in full control of the videos that they upload and can delete them or share them with other teachers in their school if they wish. He adds that schools sign a licence agreement that ensures the system is used within the appropriate legal framework set out by the Information Commissioner. The agreement also requires that the school commits to using the system only for the purpose of CPD and that this is communicated with parents formally.

Although Newell says he is personally not in favour of the use of bodycams in schools to monitor student behaviour, he admits that there have been incidents in the past where the company’s technology has been used to great effect in this regard.

“We are aware of instances when the teacher - with the consent of pupils and parents - has recorded video and then given it to the pupil to observe their own behaviour,” says Newell.

“That was really constructive and, according to the teachers concerned, the drop in misbehaviours in that classroom by particular pupils was quite remarkable.”

That might be enough to persuade some teachers who were opposed to cameras to at least look again. But having a static camera like this is very different to a wearable one, argues Linda Graham, associate professor in the School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education at Queensland University of Technology. She researches the contributions that school policies and teaching practices make to the development of disruptive behaviour and believes that if CCTV is on site already, then every aspect of the school should be covered (but she is against any cameras on site, ideally). Graham says that such coverage should be with a static camera, not a wearable one.

“If the teacher is wearing a camera [as opposed to a camera being on the wall], that suggests students are the only object of surveillance, but I’d argue that all classroom participants should be subject to the same scrutiny,” she argues.

For the record

The evidence from the police trials, though, did suggest a change in behaviour of (and increased scrutiny of) the wearer, as well as those the camera was pointed at.

With the data and privacy concerns shown to be easily manageable, as well as apparent behaviour improvements, added potential benefits for CPD and a third of teachers being in favour of bodycams, perhaps having a third eye looking over the classroom is not as unlikely as it first seemed.

If the cameras are implemented correctly, Ellis says, doubting teachers would soon come around: “Asking permission from pupils to record positive events could help reduce reaction against them. Teachers might begin to feel more at ease with the cameras once a broader range of uses is developed and it might allow a more graded disciplinary system to be developed to involve restorative approaches.”

However, two significant hurdles remain. The first, as you might expect, is money - with school funding in a desperate state, it is unlikely that these cameras could be afforded. The ones used in US schools cost about $85 (£67) a piece.

Secondly, even if schools could afford them, the bigger challenge would be teacher buy-in. However excellent the implementation, for many teachers the use of a camera would suggest a lack of trust in, and a lack of co-operation and relationship with, students. Wearing a camera could be seen as an admission that you - and the school - have failed in what is a key element of teaching: to build an effective partnership with those you are there to educate.

One respondent to the TES survey summed up this problem: “Our relationship with students is the single most important factor in teaching. Why would we want to start that relationship from a position of mistrust, from an expectation they are not there to learn and behave?”

No matter how bad the behaviour in a school may be, or how successful a bodycam might prove for solving this issue, persuading many teachers to change that belief would seem to be a near-impossible challenge.

Simon Creasey is a freelance journalist based in Kent. He tweets @simoncreasey2

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters