- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Specialist Sector

- Maggie Snowling: Why schools need to look beyond dyslexia

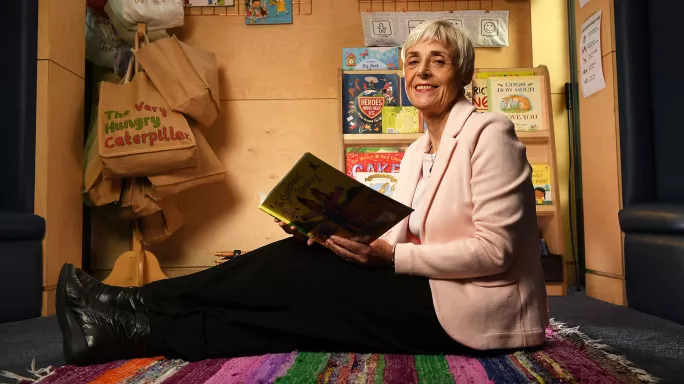

Maggie Snowling: Why schools need to look beyond dyslexia

When former health secretary Matt Hancock raised the possibility of introducing a screening check for dyslexia, Maggie Snowling had a thing or two to say about it.

“I talked to Matt Hancock quite a lot, telling him we’ve already got dyslexia screening: it’s called the phonics screening check,” she says.

Snowling is a world-leading expert in reading and language difficulties, and was made a CBE for services to science and the understanding of dyslexia in 2016. Now emeritus professor in psychology at the University of Oxford, she continues to offer advice to policymakers.

“What the government should do is mandate that if a child doesn’t reach the expected standard in phonics, they get an intervention. Because at the moment some do and some don’t. The information [from the screening check] is all well and good, but we need to act on it,” Snowling explains.

Dyslexia is not her only area of focus. Snowling also played a part in initiatives that have shaped literacy teaching in the UK, including being on the advisory group for the Rose review and the phonics screening check. She also, along with her husband, Professor Charles Hulme, developed the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI). Between 2020 and 2022, this was offered to all primary schools, fully funded by the Department for Education, as a strategy to tackle gaps in language development at school entry.

And while it’s important to champion dyslexia awareness, Snowling believes there are lesser-known literacy difficulties that also deserve our attention - difficulties, she says, that often “get missed”.

We sat down with her to find out more.

Tes: Throughout your career, you’ve raised the profile of dyslexia, but what other literacy difficulties should schools be aware of?

Maggie Snowling: There are lots of other difficulties. For example, there are children with reading comprehension impairment, which is sometimes called the poor comprehender profile. These are the children who can decode but have problems in understanding what they read. In an extreme form, it’s sometimes been referred to as hyperlexia, where there’s a decoupling of print from language.

There are also children, and this might include autistic children, who actually have got reasonable vocabulary and reasonable grammar but they don’t use inferences. They read the text fluently but don’t engage with the context. This leads to problems with the more subtle aspects of meaning. They might be able to retell a story verbatim but they’re not developing a proper mental representation of the text. This doesn’t have a name but in literature they are referred to as “poor comprehenders”.

‘There’s less awareness of children with developmental language disorder, and there’s less research’

Then there are children who have developmental language disorder: they have both serious and persistent oral language problems and problems with reading and maths. These are the children who are really hidden in our classrooms.

Why do you think that is?

The characteristics of children with dyslexia and autistic children are now quite well understood. But there’s less awareness of children with developmental language disorder, and there’s less research. These are the children that speech and language professionals really have the skills to look after. But we’ve had lots of cuts and there aren’t many speech and language therapists in the education space these days.

How many children face these challenges?

The problem with talking about prevalence is that it depends where you put the cut-off for the difficulty. You can say 5 per cent of children have dyslexia; that’s just because you’ve taken the bottom 5 per cent on a reading distribution, and you could do the same for reading comprehension impairment.

We used to think that there are as many children with reading problems as with reading comprehension problems, but Charles Hulme and I are currently trying to develop a tool for reading comprehension because no screening tool exists.

A lot of teachers are reporting that higher numbers of children are suffering with speech and language impairment following the pandemic. Do we have evidence that there is a wider trend here?

It’s an interesting question because there’s been a lack of measurement in the past. Historically, reading and dyslexia have always been the focus for the government, and therefore school systems have emphasised literacy and teaching children to read, and there hasn’t, until relatively recently, been much emphasis on oral language.

But I would say that in the past five years the tide has changed, and people are much more tuned in to the importance of early language as a foundation not just for literacy but for everything in education. Our curriculum is delivered through language.

Is it a growing problem? We don’t have the measures to say for sure, but obviously during the pandemic there was a lot of concern about children in the early years being out of school, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds where the linguistic environment might not be very rich. So, it is very much on people’s agendas now and action is being taken.

The Nuffield Early Language Intervention is part of that action, and has now been used by 11,000 schools. Why do you think it’s had such a big uptake?

NELI appeals to the professionals delivering it because it’s about language, and that is second nature to most teachers. It seems very natural, rather than something forced upon children from a curriculum devised by policymakers. Of course, the children’s response to it is very positive, and that reinforces the attractiveness of the intervention.

It’s a two-way process. I think the people delivering it like it, and the materials are child-friendly and easy to use, so the children enjoy doing it. The teaching assistants or the teachers can see the progress of the children, which, again, is reinforcing.

Some have raised concerns about schools’ fidelity to the programme. Why do you think this is?

With any intervention, resourcing can be an issue for schools. You may not have a teaching assistant to deliver it; that teaching assistant may not have anywhere to work. The time in the curriculum might be restricted and there might be a feeling that other things have to suffer.

But you could say that about any robust intervention. There are other interventions that you can fit in but actually, they don’t work.

If you want to have a programme that is actually going to help pupils, you’re going to have to be committed to it, and it’s going to take time. Resourceful teachers, classrooms and schools can fit it in, because they know language is a priority in the early years; children need a foundation in oral language in order to learn, to communicate with one another and to develop friendships.

Others have criticised NELI because it stops at early years foundation stage (EYFS). How can schools support those children who still have difficulties once they’ve completed the programme?

We don’t pretend that NELI is a complete fix; it’s not a cure. It’s the first building block in a pathway to helping children with language learning difficulties. There will be some children who don’t respond very well to NELI, and who have more severe and persistent problems.

- Early language: Third of primaries yet to sign up for NELI catch-up scheme

- EYFS: Language catch-up scheme “beneficial” but time consuming

- Developmental language disorder: what you need to know

Of course, we focus on the positive outcomes of a language intervention, but an absence of a positive outcome is also helpful. It shows us that these children need a referral to a specialist service because they probably have special educational needs.

Are there enough checks in place to identify children who may need extra intervention or external support?

For the past 10 years we’ve had the phonics screening check in place at the end of Year 1, and this certainly is helpful. However, I’d argue - and I did argue when I was on the expert group in 2011 - that this check should include a vocabulary measure. People worry that this would lead to teachers “teaching to the test”, but actually that would be quite a good thing here. Vocabulary is so important because not only does it help you develop knowledge, it also helps you infer things, it helps your reading, it helps your interactions.

I’d also argue that if we want to increase the probability that we’re going to identify the right children, we probably should be doing some checks around school entry or in the term before they start school. There seems to be a desire to conduct these checks even earlier than that, but I think that’s not so important.

Why is that?

Well, the earlier you go, the more individual variability there is in development. We know from research that some children with speech and language difficulties at age three and a half do resolve their language problems by five and a half.

If you had really early intervention, let’s say at three and a half to four, you need to make sure you’re not treating kids who are going to actually develop and catch up anyway. If we wait until language has become more stable then we can identify those who have long-term difficulties.

Should there be further checks in key stage 2?

I do think there is more we could do in Years 4 and 5. If we could have a screening then, it could lead to intensive intervention before transition to secondary school. It is quite late for intervention but, just as some children develop literacy problems at a young age, there are those who have late emerging problems.

The other children who come into focus around Year 4 and 5 are children with reading comprehension problems. There may be children who’ve learned to decode fairly well and have done quite well in phonics but have got problems in understanding what they read.

In an ideal world we’d have a language screening at age 5, a reading screening at the end of Year 1 and then a broader reading and language assessment, which involves reading comprehension, in Year 4.

However, it’s not just about the screening but the intervention that follows that.

What sorts of interventions work best?

When it comes to children who fail the screening test in Year 1, my opinion does differ from current policy.

My concern is that intervention just means more phonics, and while more regular in-depth phonic work with a skilled practitioner will help, the work we’ve done suggests that, at that point, it’s quite important to combine this with explicit work linking phoneme awareness and letter sounds, and practising these links while reading from books.

These shouldn’t be the decodable texts that are in the phonics teaching system but real books at the right instructional level. While it might be desirable to practise your phonics in a decodable text, the truth is that most books are not decodable, and children have to have strategies that will enable them to decipher unusual words.

I’m not suggesting we encourage children to guess words, but there’s some evidence that says if you show children unusual words - for example, “stomach” - they will probably get it wrong. But if you train them to think, ‘Is there any other word you know from your vocabulary that would make sense in that sentence?’ then that can help.

So, encouraging reading for pleasure is a key strategy at this stage. Of course, phonics has to continue; it’s a priority. But children get so much phonics at school. At home, they are often using other skills when they’re reading for pleasure or reading to their parents.

What can schools do to better support children with language difficulties?

Well, I think for any child with a special need in the classroom, we need a teacher who is aware of individual differences in learning. That’s the first thing. And to have that, we need teacher education that provides more background in individual differences in language and reading, because I think most new teachers still come into the classroom thinking it’s a level playing field.

Teachers need to be aware of their own language use. When giving verbal instructions, for example, it’s important to check that the child with language difficulties is on the same page and not just following their neighbour. So, having that child in your visual field is quite important.

‘Teachers shouldn’t feel that they have to wait for an expert’

It’s very important to work on vocabulary, too. It depends on the age of the child but you should ideally go through the language of the curriculum area before it’s delivered. This is particularly important in secondary, and should be delivered like a glossary of terms, so that the child knows which words are going to be part of the lesson. They’ve then got a scaffold on which to hang the concepts.

There should definitely be some language support in place. That might be through a language intervention programme that’s being delivered one on one, probably following the advice of a speech and language therapist.

And it’s also about having a surveillance system so that you can keep an eye on children’s development. We don’t want more high-stakes tests, necessarily, but when children have been identified as having additional needs, we need to be monitoring their progress and having referrals to multidisciplinary teams, when available.

I know this feels like a lot, though, for schools to take on.

What would you say to teachers who perhaps feel a bit intimidated by the scale of this work?

I think that, second to a parent, the teacher is the most important person in a child’s life - and a good teacher can transform a child’s life. With a child with special educational needs, teachers shouldn’t feel that they have to wait for an expert because, actually, experts often only know a little bit more than they do.

They can undertake CPD to learn about the diversity of children’s needs, and I would strongly encourage them to do that. It’s important to understand that there are individual differences in children’s needs and to always have in your mind a programme for that individual child, which is about enabling them.

But that’s what good teachers already do. They don’t pretend they’re a dyslexia expert but they know what dyslexia is. They know that child needs help and they’ll go all out to get that help in place for them.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article