- Home

- Book review: Let Her Fly: A Father’s Journey and the Fight for Equality

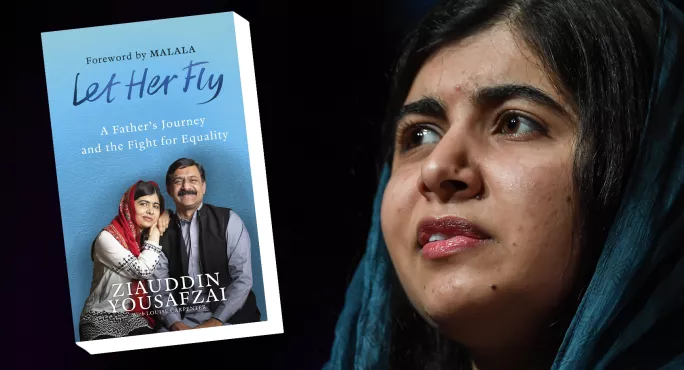

Book review: Let Her Fly: A Father’s Journey and the Fight for Equality

Let Her Fly: A Father’s Journey and the Fight for Equality

Author: Ziauddin Yousafzai with Louise Carpenter

Publisher: WH Allen

Details: 176pp, £14.99

ISBN: 9780753552964

Daughters who have good relationship with their fathers are said to have a lower risk of anxiety and depression, higher self-confidence and a positive self-image. This is certainly true of my relationship with my father, and it is clear from Ziauddin Yousafzai’s memoir that it’s true of Malala and her father, too.

Like Malala, my father was a teacher who campaigned for education, particularly for Muslims in Britain, in the same way Malala’s father fought for educational rights in Pakistan.

My father, Naz Bokhari, was born in Lahore before partition, raised by his single mother, and became a teacher at the age of 18 to help fund the education of his three brothers. Education was and still is the only way out of poverty in countries such as Pakistan.

He continued to champion the importance of education in Britain and became the first Asian Muslim headteacher in the UK. I never realised how remarkable he was until I was much older.

My father encouraged me to become a teacher and journalist, and now an emerging politician. I know now that his passion for my success was rare for people from Pakistani backgrounds. Like Malala’s father, my father did not clip my wings, but protected me until I was ready to fly on my own. Before he passed away, he said: “I have every confidence in you to succeed.” A father’s love is powerful to a daughter and this is the strong theme throughout this book.

Foreword by Malala

What strikes me the most is how love pours from every page - from Malala’s foreword to the acknowledgments at the end. Love for everyone who has been part of this journey is the driving force for what made Malala the person she is today. You are also left with a feeling of great respect for Ziauddin.

The most striking image for me is his pride in ironing his daughter’s shalwar kameez. I could never imagine my father (despite his love for us) or parents from his generation doing this. But this is symbolic of the love and devotion Ziauddin has for his daughter. Little acts such as these are often referred to in the book. The way his mother would serve tea to his father is compared with the moment his daughter was served tea (in the British way) by an Oxford College principal. These moments signify the important elements running throughout this memoir: acceptance and reverence for everyone equally.

Ziauddin never forgets his beginnings and, despite the sometimes obvious struggles, his love for Pakistan and its traditions are woven throughout the chapters. His family were poor, but they lived in one of the most beautiful parts of Pakistan, Swat Valley. I can remember my parents often talking about the magnificent mountains and forests of Swat, and the beauty of the people of Pashtun, known for their light-coloured eyes.

Ziauddin refers to the tribal and patriarchal society he was brought up in, but there is never any sign of criticism or judgement; there is only understanding and respect. For his own father, who would never have raised his children the way Ziauddin did, there is a deep love and admiration. Zia’s childhood was a difficult one because of his dark complexion (considered in his society to be less desirable) and stammer. His confidence was low, but through his own determination, he was able to find a way to take part in school debates and even later become a teacher himself.

The experiences of his mother and later his stepmother formed Zia’s differing perspective of women, but it was the suffering of his cousin who tried to escape an unhappy marriage that really led Zia to fight for women’s rights. He saw how women suffered from inequality and a lack of independence. This was something that he promised he would protect his own daughter from.

Toor Pekai’s influence

The memoir is separated into sections focused on father, sons, wife and best friend, and daughter, and each touches on how Ziauddin’s upbringing, fight for equality, the Taliban and the shooting of Malala affected their lives.

The relationship with his sons is incredibly moving, but it is the relationship with his wife, Toor Pekai, that is the most thought-provoking. Suprisingly, she is the real hero, the strongest role model, the real feminist in her family. She is often forgotten in Malala’s inspirational story, but it is Pekai who is the real force. She championed women in her village to go to school and supported her husband to fight for equality. Her story is the more powerful because she had no education; she could not read and write, yet she knew more than anyone else how important education was.

Likewise, my father always admitted that, were it not for my own mother, he would never have achieved what he did or raised his children with such high aspirations.

Pekai, is the most inspirational person story in this memoir. Her journey is the most difficult. Her life was rooted in Pakistan, she had a purpose and a belonging. After her daughter’s shooting, she was the one who had to fight for independence - and she did this on her own.

In Britain, she was alone. Her children had school and her husband had work. Her stories mirror those of many women who have no English, yet are just expected to assimilate and become part of British society. It is her resilience and perseverance that have enabled her family and Malala to survive and thrive. She is the reason we have Malala’s voice speaking for girls and education, and I think this is why Ziauddin wrote this book. He wanted us to hear the mother’s story, her passion for her daughter.

A father’s story is a mother’s story, too.

Hina Bokhari is a former teacher and journalist, and is now a Liberal Democrat councillor. She tweets at @bc_hina

You can support us by clicking the book-title link above: Tes may earn a commission from Amazon on any purchase you make, at no extra cost to you

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters