- Home

- Book review: Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me

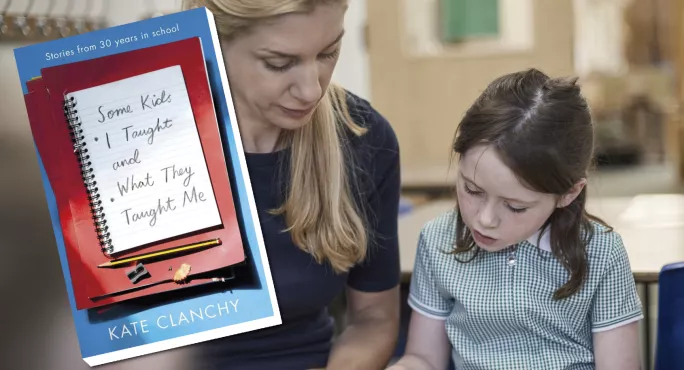

Book review: Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me

Author: Kate Clanchy

Publisher: Picador

Details: hardback, 288 pages, £16.99

ISBN 978-1509840298

I believe that teaching is the best job in the world, and that it is a privilege to teach young people. However, at a time when it can feel like an uphill struggle against swingeing cuts and ever-increasing pressure to produce results, Kate Clanchy’s book is a golden reminder of why we chose to enter the profession.

By focusing on individual stories, Clanchy delves into the real human experiences of the relationships that teachers have with their students and with each other, which make schools such vibrant, fun and at times heartbreaking places to work.

She doesn’t avoid the uncomfortable wider truths, recognising that the current system of selective schools (whether by ability, religion or the murkier, more slippery class system) inevitably means that, while there are some winners, there are many, many more losers.

She suggests that there is no empirical evidence to suggest that grammar schools are effective, and that the grammar system is led by successive politicians who felt the benefit of the grammar-school education and therefore wish to emulate it. She posits that this is a terrifying dereliction of duty towards those children who do not show exceptional ability at age 11, or whose parents cannot pay, or have other barriers, such as a lack of English-language skills, and who are left to attend the local comprehensive, regardless of whether or not it is good.

Clanchy also holds strong views on exclusion. She recognises that the schools she teaches in - the “rough” comps - are more likely to have to deal with students with complex needs, as well as grinding poverty and generations of unemployment. But she reminds us, through stories of individuals, that these are young people in extremely challenging circumstances. Once schools make the decision to exclude, they are more often than not writing off a young person’s future.

The author is not naive; she has taught for many years, and recognises the impact that volatile and vulnerable students can have on the rest of the class. Her grappling with this issue resonates strongly, as it is one that never goes away and weighs heavy - as it should do - on school leaders.

A comparison between Miss B and Miss T, apparently dichotomous teachers, is interesting. Miss B is the inclusion teacher who is only able to teach holistically and recognises the context within which each child operates. Miss B uses every strategy at her disposal to support and to help children make the right decisions, including climbing a tree to talk to a distraught student who happens to be about 6ft 3in and armed with a knife. Happily, she gets him down and the knife is retrieved.

Miss T, on the other hand, is committed to “outstanding” outcomes at all costs, teaching with iron discipline and pushing students to perform well. In the process, she earns their full respect.

As teachers, we all recognise these characters in our schools, and recognise that each has their own way of working, which is successful for most students most of the time. In the current climate, and if Twitter is to be believed, these teachers represent the “trad” and “prog” sides of education, and never the twain shall meet. In reality, of course, we often see teachers using their unique strengths to bring out the best in students, and students adapting to each teacher and situation, lesson by lesson, and without a moment’s hesitation.

Within this context and with her political and moral opinions explicit, Clanchy writes movingly about the power of language - specifically poetry. She writes about how poetry can help marginalised young people to have a voice, and to write with a beauty that makes others pay attention. She highlights the fact that poetry, like other arts subjects, does not always fit into neat categories of what has been learned, or will not sit happily alongside the assessment checklists so beloved by data managers or those who need to show progress every five minutes.

She highlights the importance of providing creative outlets that encourage children to speak their own truths, and to do so eloquently and powerfully. This is exemplified several times throughout the book, and being fully aware of the students’ back-stories provides even more depth and resonance to their words.

I loved reading this book. I found myself nodding along in recognition - at student behaviour, teacher passion, the bizarre situations one sometimes finds oneself in in teaching, and the frustrating environment of teaching to a test and the skewing influence of external data. Similar anecdotal books I have read about students in difficult circumstances have felt exploitative, like poverty porn, but this feels like a teacher standing side by side with her students and fighting for them. Clanchy comes across as principled, passionate and empathetic, and writes evocatively with precision and subtlety. I did not agree with all of her assertions, but I very much enjoyed this book.

Victoria Tully is deputy headteacher at Fulham Cross Girls’ School, in West London

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters