- Home

- The horror of special measures

The horror of special measures

That evening was like being at a wake. Worse. I was so junior and so innocent that I was like a happy apparatchik at the wake of Kim Jong-un. Misplaced. And dangerous.

“It’ll be alright. We’ll get out of this,” I said.

My enthusiasm was met with tears, death stares and the silence of the crypt.

For the next four years, I would be a zombie teacher. At that moment, the day my school went into special measures (SM), I didn’t know I’d been bitten - not yet the walking dead, but a dead man walking.

What follows is my account of being in a school in SM. We hear stories of miraculous turnarounds, but seldom do we hear about the failures. Even rarer still are the stories of the people caught up in it. Our system could do with more of those tales being told.

Because SM destroys teachers, it destroys careers and it destroys schools.

Dawn of the Dead

The school was visited by Ofsted on the same two days that I was there for interview. As I got my good news (“we’d be delighted to appoint you”), the school got its bad news: it was “satisfactory” (remember when you could be that?).

Far from being put off, I relished the challenge of making things better.

For example, behaviour was highlighted as a specific issue. Well, a blind man could have picked up on that - and, to be fair, a whole team of them did. (Pats on the back, everyone.) But I knew that all these children needed was inspirational teachers. Like me. (Yeah. I know.)

I arrived with three years’ experience. I harboured a vain hope of preventing some of the failure that I’d spent my initial career picking up and dusting down.

I immediately thrived in the pastoral role of being a sixth-form tutor. Within my first two years, three of my students got places at Cambridge. It felt like starting anew. Exciting. Full of promise. But the virus had found its way in, and it was duplicating. The symptoms were slowly manifesting.

The Omens

You see, many things were dysfunctional at that school. Any school ostensibly run by its head receptionist - dragon-like as that person might be - is cruising for a bruising. Any school whose answer to Ofsted’s concerns about internal truancy is to install, at great expense, magnetically locked fobbed doors everywhere, is exhibiting either a shocking lack - or a Smarties Book Prize-worthy surfeit - of imagination in its response to challenges.

With hindsight, the SM judgement was inevitable. Was it the change of headteacher 12 months earlier that secured it? Or the difficulty of recruiting staff in that area?

Could it have been the non-exclusion policy adhered to by all the local schools? Or perhaps the exception to that policy granted to any school in SM?

Was it just our turn? In this selective area, one of the non-selectives was always in SM.

Was it poverty? The lack of meaningful employment and opportunities? The proportion of disadvantaged pupils (“well above the national average”)?

Who knows? The information is in the reports, but it seems to have no bearing on them.

Judgement Day

The judgement was deserved. Perhaps that’s why they cried that night - because deep down they knew they had it coming.

Or perhaps it was pity; they were looking at me, full of verve in the face of adversity, and thinking to themselves: “Bless you. You have no idea what I’m going to have to do to you now, do you?”

I was the last teacher in the room. I kept smiling, comforting members of SLT who I still thought, labouring under an illusion, were friends and colleagues.

When I left, the smile dissipated. The zombie virus was incubating.

The report highlighted two chief areas of concern: behaviour and teaching.

Leadership and management weren’t given a free pass - not that time - but evidently their failure was the failure of their teachers.

Funnily enough, the failure of the students was also the failure of their teachers. The local press, parents and students soon let us know this was the case.

What is it like, being one of those teachers?

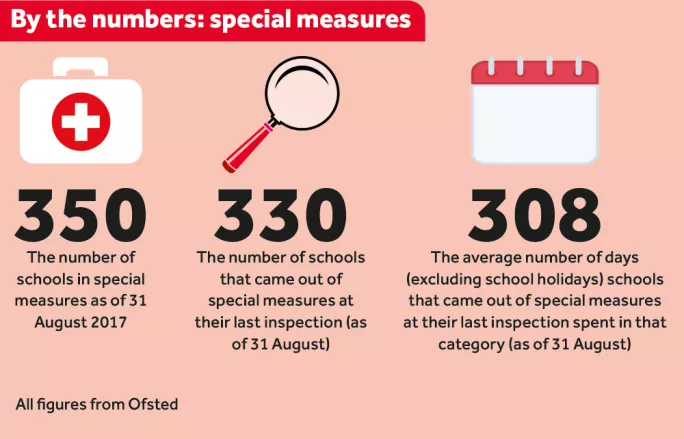

The irony - the deep, destructive irony - of being put in SM is that it only makes things worse. I’d like to add “before it gets better”, but I haven’t seen evidence of that. Judging by the number of schools for which SM has been a one-way ticket to forced academisation, I’m not alone.

What I can be certain of is that Ofsted’s judgement facilitated a dizzying deprofessionalisation of teaching.

In anticipation of Ofsted’s return within 12 months, all means were justified to improve teaching (already and unwaveringly identified as the source of poor behaviour). In fact, the only evident “rapid, sustained progress” was in the increase in workload, distrust and policy generation by SLT.

The “rapid graspers” were those who left early. I did not have that level of insight. I was committed to getting us out of the mess, and internalised the blame for getting us into it. So I lived through it. Or rather, I was confined to a quarantine full of “infectious” teachers who only a steady stream of consultants charging by the hour wanted to see and who were subjected to a series of “treatments” - in the name of salvation - that will make you shudder.

It Follows

I’ll be blunt: if you think you have it bad where you are, unless you are in (or have survived) special measures, I dare say you haven’t quite experienced the full arsenal of what can be justifiably said of you, asked of you or done to you in the name of support.

Many are the teachers leaving the pressure cooker that our profession has become. But being in SM is like being in that pressure cooker without a release valve.

The support, such as it was, was never aimed at teachers, but at SLT. It was based on their assessment of weaknesses (which, one can safely presume, were seldom their own weaknesses), and deployed by them on to the teachers.

This is the great rigged game of the Ofsted framework. It may nominally focus on various aspects of the running of the school but in truth, wedded as it is to a top-down accountability system, it is only ever really teachers who will come under true scrutiny, be subjected to the ignominy of spurious behaviour regimes, and fall on their purple marking pens.

I saw numerous headteachers come and go during my time there. I remember two most vividly: the one who left for greater things as the school came out of SM; the other was the one who arrived as it went straight back in.

The Exorcist

Examples abound in my memory of the foolish things done by otherwise intelligent people in the name of school improvement. I wouldn’t even scratch the surface with the word limit I’m working to. So I’ll give you a glimpse of some of the many, many potions, lotions and ointments - not to mention the leeches and blood-lettings - we were prescribed.

SLT devised a lesson plan template to accompany a new policy that required every single teacher to write individual lesson plans for each and every lesson. These had to be printed and filed into a central folder (one for each class), ready to be presented to any observer upon entry to your classroom. The template ran to numerous pages.

SLT got wind, through observations, that some of the lesson plans were unsatisfactory, rushed or duplicated. Their response was to demand that all lesson plans be filed on a shared drive by the Wednesday of the week before they were to be delivered, to be scrutinised by heads of department.

Then there was the marking policy: it changed so many times, and each time, it got worse. At one point, there were stickers on which to write teacher comments and others for students’ responses, to be applied fortnightly. English, drama, PE, DT - it didn’t matter. I had 18 different classes. I wrote a PhD’s worth of words on stickers in just one term.

Then there were half-termly written reports, with subject grades, behaviour grades, attitude grades, skills grades.

And the behaviour policy? Again, there were many, and none worked - so a new streaming system was brought in, creating classes in the bottom sets where teaching was as challenging as it can ever be.

If that didn’t magically sort out the behaviour, the SLT support on-call rota would surely do the trick. Except that the rota was as well followed by them as any of their policies were by us, albeit sans repercussions in their case.

In cases where behaviour wasn’t good in your class, it was your fault and you were made to feel it keenly. Students would be removed (if you were lucky), spoken to in the corridor and reintroduced without consultation. It was our job to fill in paperwork, see through any consequences, and face that class again unsupported next lesson.

God forbid you should need support - a sure sign of inadequacy. Coaching came to be seen as a road to “capabilities”.

SLT were busy. They had learning walks to do (oh, and how many they did! Their Fitbits must’ve cooed at all the walking.). They had observations to carry out. Many, many observations. They had meetings to go to, and meetings for which they had to prepare.

Special measures meant that we were revisited by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate once a term for monitoring. There were extra resources available, like “supportive” local authority inspections and funding for “mocksted” consultants. (They don’t call it “mocksted” any more because Ofsted said “please don’t”. But they still sell their alchemists’ distillations to the infirm.)

There were times when we were observed more than once a week for weeks on end.

And what do the pupils think of that? Do they feel their education is being “specially” cared for? These are the children who already feel embarrassment in their communities for going to the “special measures school”.

In school, they now have all the evidence they need that not only the school as a whole, but also their teachers individually, are not to be trusted. Nobody doing their job properly would need this level of scrutiny.

Anyone can see what the impact of that might be on student-teacher relationships, on behaviour, on the education of the children and the careers of teachers. Anyone, it would seem, except Her Majesty’s Inspectors and members of SLT.

We began to haemorrhage staff. Irreplaceable staff. Literally. Members of SLT regularly flew to Ireland on recruitment drives.

Enthusiastic, optimistic and wilfully blind as I was, I took on responsibilities. I brought about changes that I still look back on with pride. None of them were sustainable, though, because they depended wholly on me. There was no support - only responsibility and accountability, and these only flowed in one direction.

Successive monitoring reports exonerated the leadership team while pinning the blame for the school’s ailments on teachers and teaching. Her Majesty’s Inspectors had faith in the school’s “capacity to improve”. We mortals were never consulted. The SLT narrative, or School Improvement Plan, was accepted at face value.

What was asked of us - the treatment killing the patient - was normalised and given validity by those entrusted with the power to question it. I can’t even bring myself to blame the leadership team for any of it. They were responding, to the best of their ability, to a system that left them little room to do otherwise.

Where was anyone’s duty of care for us? I remember a kind-hearted teacher, who rose to the top with a focus on staff wellbeing.

The school embraced him, signed up to a wellbeing support helpline (thereby ridding themselves of any further responsibility to consider the pesky thing). There was going to be an anonymous wellbeing survey, a chance to voice opinions about the running of the school. The veterans grumbled - and I resented them for it, truth be told.

When the survey came out, it was clear that any respondent could be identified with three questions. If there were any doubts, the fact that it was designed for handwritten answers killed those off. The uptake hovered around 30 per cent. It was a whitewash.

Behaviour didn’t improve, as such - can you believe that? - but the number of incidents dropped as exclusions rose. As I understand it, the school as good as ruined itself financially paying for alternative provision.

When we got out of SM, scrambling to the dizzy heights of “requires improvement”, many of the students in alternative provision were reintroduced - for financial or ethical reasons, I know not, but I have suspicions.

Our “successful” headteacher moved onwards and upwards. A new superhead was appointed to keep us on course. Within a year, the school was back in SM. Then he left.

Scream

I never saw the dawn of academisation that followed. I got ill. Really ill. A simple virus, yet there was nothing left of me to fight it. Years of SM, of high-stakes accountability on steroids, of optimism in the face of repeated physical and mental stress had ensured that this was so. The virus had finished incubating and I succumbed to its physical manifestation.

In the midst of that, I received a phone call asking me if I could come back in.

Can you guess why? Yes. Ofsted had called.

A botched return to work aggravated my condition and brought on debilitating anxiety, and that’s where my career as a full-time teacher and “promising future leader” ended.

The stigma, the suspicion you’re faking it, the underlying judgement that you just weren’t strong enough - they’re the hardest to get over.

Illness, you can beat, but the judgement of others is almost inescapable. It didn’t just come from SLT, either. It came from almost everyone. There’s a kind of resentment when you’ve found a way out of the pressure cooker. Colleagues and friends turn away from you. Others momentarily grieve your loss, then get on with it. And what choice do they have? Your absence has only increased the pressure on them. How do I know that? Because I was the same when it happened to others before me. Too many others.

That’s our education system’s reward for committing yourself to a challenging school and to its students, for refusing to give up, for being idealistic enough not to leave. You’re only one virus away from becoming a zombie. And everyone knows it.

All the indications are that the virus is spreading. Some try to save themselves by moving to better schools or teaching abroad. Some by giving up on the profession or becoming supply teachers.

A very few seem to be immune to the virus, others go into work in full hazmat suits made of nonchalance and dispassion. Good luck running an education system with only them.

But fear the walking dead - your colleagues, infected by a punitive system they can’t escape or resist.

And the school? They call it something different, but I know it’s the same. The O-Men know it, too, though they’ll pretend otherwise. It continues to have difficulties recruiting and retaining staff. Leadership are still taking effective action to improve behaviour and learning.

Round and round she goes - a savage indictment of both Ofsted’s supposed school improvement role, and the government’s con trick of forced academisation.

But its previous rating has been expunged, so that’s good enough for Ofsted, the DfE, and the secretary of state, who can remove the students on its roll from the statistics of children being taught in “inadequate” schools.

Something is rotten in state education. The medicine of SM is killing its patient.

So here I am, three years in recovery, a supply teacher in your school. I see many teachers. Some on the way up. Some on the way down. Most blown about left, right and centre in the changeable winds of political interference. I have a unique experience. But will you hear my voice? What I have to say might scare you, but not as much as finding the walking dead inside your school gates.

The writer is anonymous and some minor details of the story have been changed to protect their identity

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters