- Home

- How America fell in (and out of) love with testing

How America fell in (and out of) love with testing

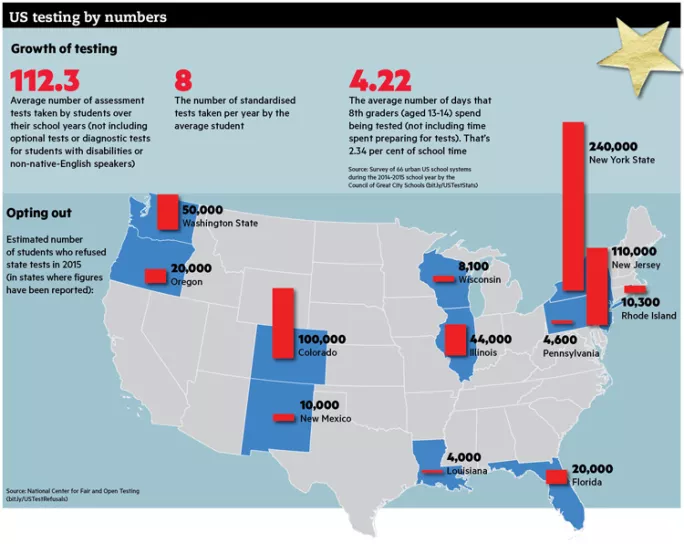

In the spring of 2012, in the small town of Snohomish, Washington, 550 sets of parents refused to let their children take the state Measurements of Student Progress test. Their reason was primarily to protest against the high cost of holding so many exams at a time when education spending was falling. Teachers were being furloughed, class sizes were increasing, and maintenance was being cut, all while more tests continued to be added. At first, the protest seemed to have little impact: nationally, the number of tests continued to increase. By the end of the 2014-2015 school year, the average student was taking 112 mandatory standardized tests (eight per year) between pre-kindergarten and the end of high school, according to the Council of the Great City Schools, an association of urban school districts.

But today, the Snohomish parents’ relatively small act of defiance is widely regarded as one of the first serious assaults of an anti-testing movement that has now seemingly changed a nation’s mentality. Testing in schools was an obsession in America with cross-party support, but suddenly the country has turned against it. So complete has the turnaround been that anti-testing campaigns in other countries are using the US example as a motivator and evidence of how things can change. Yet delve deeper, and there is a question as to whether anything is actually changing at all.

America’s love of testing had its roots in the national soul-searching that followed the 1983 release of A Nation at Risk, a report pointing out that students’ scores on university admissions tests were plummeting and that the US was falling behind in international comparisons of educational outcomes.

But the report - the work of a presidential commission - was not the start of the rush towards testing; rather, the confirmation of a movement already in progress. That movement began when the Texas legislature approved the Texas Assessment of Basic Skills (Tabs) in 1979 to measure where the failings later highlighted in A Nation at Risk were occurring. Tabs was a series of nine tests given in the 3rd, 5th, and 9th grades. It was the first of numerous state programmes across the US that would become known by their alphabets of acronyms. As testing became more prevalent in the following decades, the number in Texas alone grew to a mammoth 27.

Much of that expansion came during the term of one particular governor of Texas: George W Bush. And when Bush went to Washington as president in 2001 - replacing Bill Clinton, whose Goals 2000 policy required states to identify low-performing schools, prompting an increase in testing - he took his fervour for testing with him. On his third day in office, Bush proposed the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act. This called for states to give assessment tests to every student in maths and reading every year between the 3rd and 8th grades, and once in high school. It was a popular plan, backed by Bush’s fellow Republicans and the opposition Democrats alike, and passed in the US Senate by a vote of 91-8.

To receive federal education funding, each state was directed to develop annual assessment tests to measure basic skills. If these tests did not show that the outcomes of schools serving low-income students were improving, the state had to put in measures to assist those schools. If a school did not show progress for five consecutive years, it could be restructured and its entire staff replaced.

Before NCLB, federal law required that each student be assessed once in reading and maths in elementary, middle and high school - a total of six times. The number of tests required by NCLB alone had now increased to 17.

Growth spurt

Despite some disagreement as to the effectiveness of the NCLB tests - and testing in general (see below) - when president Barack Obama arrived at the White House in 2009, the number of assessments was again increased. The economic crisis had begun, and state and local tax revenues that supported services including schools were crumbling.

To shore them up, the Obama administration shoveled money into programmes such as Race to the Top (launched in 2012), which offered billions of dollars to states that agreed to further expand their testing regimes. The test scores were now used in some cases to evaluate teachers and determine their salaries - or even whether they would be allowed to keep their jobs.

With the stakes so high, some states and school districts added their own tests on top of the national initiatives to make sure that students were on track. Most of the tests now being given in American schools are required not by the national government but by local ones.

“What we had was a push for assessments that were technically strong, more standardized, longer and tougher,” says Chris Domaleski, associate director of the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment. “But the accountability didn’t just touch the students - it touched the adults now.”

Some of those adults tried to game the system. For example, eight teachers and administrators in Atlanta were given jail time for tampering with test scores - a scandal that was exposed in 2013 and was found to have involved 178 teachers and school principals.

“Educators unethically, and in many cases illegally, did whatever they could to boost the scores,” says Bob Schaeffer, public education director of the National Center for Fair and Open Testing, or FairTest, which works against the “misuse of assessment testing”.

But policymakers stuck to the tests. An unlikely political alliance formed, combining liberals who thought that tests could force the country to deal with socio-economic and racial disparities in education, and conservatives who believed that putting sanctions behind assessment tests would bring market forces to bear on schools.

And parents continued to stand by tests. Seventy-five per cent of those questioned in a 2013 poll by the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research said that standardized tests were a good way to measure their children’s aptitude, and 69 per cent said that they were a good way to gauge the quality of schools. Only a quarter thought their children took too many tests. But the tables had begun to turn in that little town in Washington.

The beginning of the end?

After the Snohomish protest, civil disobedience spread slowly. The same year, two students at an elementary school in Maine refused to take required tests, and 1,427 did the same in Colorado. Then parents at 61 schools in the state of New York declined to let their children take a “field test” - a new exam being developed for 4th-8th graders. This was still a tiny number compared to the 900 New York public schools in which there were no boycotts, but momentum was growing.

The anti-testing movement was fueled in part by aggressive union opposition to tying teacher evaluations to results, but concerns from parents played a big role, too. By late 2014, two-thirds of public-school parents in a poll by Gallup said that the emphasis on testing had grown too great.

“Five or 10 years ago, the most prominent feedback we were hearing was that the tests weren’t rigorous enough, and we saw the field respond to that very effectively - you might even say, too effectively,” says Domaleski. “Tests had gotten longer and much tougher.”

Many of the parents who pushed back against the tests were affluent and lived in suburbs where the schools were already good. Outgoing US education secretary Arne Duncan quipped at the time that the anti-testing opposition consisted largely of “white suburban moms” who were learning that their children weren’t “as brilliant as they thought they were”.

But Ilana Spiegel, an early anti-testing activist, argues that the policymakers should have asked themselves, “Why have you lost public support from the people this makes look good?” The answer, she says, is that, “People were questioning, what’s the individual value?” The addition of so many tests required by national law “was very undemocratic, top-down. So what you were seeing was the bottom pushing up,” she says.

In some places, the establishment initially fought back. Most states refused to drop a requirement that high-school students needed to pass exams to graduate. In 2012 in Colorado, school districts where more than 5 per cent of students failed to take the tests were dropped one level on the ranking scale, while at least one school in California warned that students who opted out of the assessment tests would be banned from graduation ceremonies, extracurricular activities and athletics. As recently as last year, the Illinois State Board of Education told parents that skipping the tests would be breaking the law, and Ohio said students could be held back if they didn’t take and pass their reading tests.

But then the Common Core - a national standards initiative that was backed by most state governors - was introduced. And that tipped the scales.

It wasn’t necessarily the standards that parents objected to; it was the increased number of tests that came with them. It didn’t help that many states rushed - and, in some cases, botched - the introduction of the first Common Core tests in early 2015. Servers crashed and, in 20 of the 50 states, there were problems obtaining results.

“Imagine that you’re a 3rd grader sitting in front of a screen to take a test that will determine whether you’re going to be promoted, and after you answer three or four questions, your screen goes blank,” says Schaeffer. “It was just an awful roll-out.”

In November, a panel of school psychologists in New York issued a report saying that the Common Core assessment tests were making students even more stressed than the many other exams they had taken. Even before that, by the spring of 2015, the parents of 500,000 children had refused to have them tested.

The states began to see where this was headed. By November, seven states had repealed their requirements that students pass exit tests to graduate from high school. Four reversed their policies requiring students in lower grades to pass assessment tests in order to move up a year. Colorado stopped censuring communities where students wouldn’t take tests. Lawmakers in Illinois also introduced a bill that would let parents decide if their children should be tested. And Texas cut the number of state tests from 15 to five.

The political coalition remained, but turned itself around. Now Democrats were against the high-stakes tests that their teaching union allies hated, while Republicans - the earliest backers of test-based reform - decried the added testing as a federal intrusion on local control.

And then, in October, Obama joined the chorus. “When I look back on the great teachers who shaped my life, what I remember isn’t the way they prepared me to take a standardized test,” the president said.

The US Department of Education told states and school districts to give fewer tests and spend no more than 2 per cent of class time on assessment testing. “Learning,” the president said, “is about so much more than just filling in the right bubble.”

Old habits die hard

NCLB has now been replaced at the national level by the Every Student Succeeds Act, a bipartisan measure that still requires testing but expands the way that a school’s performance is measured by considering other factors, and includes an audit provision to serve as a check on over-testing.

So, has the level of testing in the US now been reduced? And is America now the world’s anti-testing champion?

Arguments from both sides continue to be fought. Unions remain unhappy that, under the new law, teachers can still be evaluated based on student test results, although they seem to be gratified that this decision will now be up to individual states. Civil rights organizations, meanwhile, say that relying less on tests to measure differences between schools that serve different groups will allow the country to fall back into the rut of treating poor and non-white students differently.

“We cannot fix what we cannot measure,” a coalition of 12 national civil rights groups wrote to Congress. Administering standardized tests to everyone is “the only available, consistent, and objective source of data about disparities in educational outcomes.”

But 200 other groups, including several that promote racial equality, also wrote to Congress urging it to further reduce the dependence on testing.

“Measuring more doesn’t solve the problem. It’s a diversion from solving the problem. It takes resources away from what might be needed,” says Schaeffer.

One reason for the continued disagreement, argue some commentators, is the lack of an alternative to testing as a reliable means of judging educational performance.

“We needed a way, and I would argue we still need a way, to have a common gauge across communities and across jurisdictions where we can compare the performance and success not only of schools but schools with different types of kids,” says Sonja Brookins Santelises of the Education Trust, formerly chief academic officer for Baltimore City Public Schools. “The way that we’re able to hold ourselves accountable as communities is by having some kind of common measure that enables us to do that.”

She does concede that there may be too many tests for American students - and teachers - to contend with. “That’s what the anti-testing movement is trying to address, but it’s missing what the actual intent of the tests was. It wasn’t until we had common measures that even as educators we could say things like, ‘Wow, there are whole groups of kids that we are under-educating.’ ”

But the number of those common tests were never as high as some assumed, argues Andreas Schleicher, who oversees the education and skills directorate at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (see box, below). And neither are they, despite what you might think from all the rhetoric, necessarily reducing in number.

After all, while many states are trimming the amount of testing in their schools, the new law does not actually reduce the federal requirements. There will continue to be federally mandated assessment tests in reading and maths each year from 3rd-8th grade and once in high school, plus science tests three times between the 3rd and 12th grade - although states will have more flexibility to develop and score them as they see fit.

And, as Domaleski says, with all this practice, tests have never been so good. In fact, the Obama administration has spent $360 million (£238 million) on developing new school assessments.

“Most state standardized assessments have never been better than they are right now,” Domaleski adds. “It’s unfortunate that they have come about at a time when tolerance for investing in testing is waning. I’m hopeful that there will be some patience to see these through.”

Santelises says she’s optimistic, “because what we see [in these new laws] is not an abdication [of testing].”

Disappointingly for those ready to celebrate the US as an anti-testing poster child, recent developments may simply mean a refocusing of the debate, rather than an abandonment of testing altogether. It seems that in America, for now at least, exams are here to stay.

How effective was George W. Bush’s testing regime?

The effectiveness of the US assessment tests required by the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act - the brainchild of former president George W Bush - were, inevitably, measured by another test: the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which began before the NCLB came into effect in 2002.

The NAEP shows that maths scores for 4th graders have improved since NCLB began, although they were already on an upswing, according to an analysis by non-partisan thinktank the Cato Institute. There has been a very small increase in 4th grade reading scores, too. Black and Hispanic 4th graders have also had gains, but it’s hard to attribute these to NCLB, since, again, they began earlier and have continued since. Test results for older students, in their final years of secondary education, have remained flat.

In spite of improvements in the lower grades, NCLB and its related tests have had “no discernible effect by the time students neared the end of elementary and secondary education”, Neal McCluskey, associate director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, testified to Congress.

Test-based incentive programmes that hold schools accountable for students’ test scores also haven’t closed the educational performance gap between the US and its higher-achieving international rivals, the independent National Academy of Sciences points out.

The gains that have occurred, the academy reports, are small, and in some areas “effectively zero”.

Advocates of NCLB, on the other hand, cite a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research that says tying teacher evaluations to student test scores has improved schools in other ways. Students whose teachers help them to raise their scores in the 4th-8th grades are more likely to go on to university and earn higher salaries, and girls are less likely to become pregnant as teenagers.

Replacing a teacher who is ranked in the bottom 5 per cent for test scores with one who’s results are average can raise a student’s lifetime income by more than $250,000, the report finds.

But scholars at Stanford University conclude that, since the start of NCLB, and in some states, the best teachers tended to leave the low-performing schools where they’re needed most and go to higher-performing ones.

The Stanford team say that it isn’t possible to know if the accountability measures have caused this exodus of educators. But since the start of the NCLB, the most experienced teachers have become more likely than newer teachers to quit the field altogether.

Are American students really over-tested?

“The US is not a country of heavy testing,” Andreas Schleicher, who oversees the education and skills directorate at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), told the non-profit US education journalism organisation the Hechinger Report last month.

“According to Schleicher’s reading of the data from more than 70 countries, most nations give their students more standardized tests than the US does,” writes contributing editor Jill Barshay. “He notes that the Netherlands, Belgium and Asian countries - all high-performing education systems - administer a lot more.”

The data was from 2009, but Schleicher says he does not expect any major changes in data to be released later this year.

Some have published counter claims, including education expert Diane Ravitch. Ravitch quotes Pasi Sahlberg, Finnish educationalist and visiting professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, as saying: “My experience based on school visits and many discussions with parents and teachers around the US suggest quite the opposite.

“I don’t know any other OECD country where cheating and corruption are so common in all levels of the school system than it is in the US, only because [of the] dominance of standardized tests.”

The jury, it seems, is still out.

Jon Marcus is an education writer based in Boston @JonMarcusBoston

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES USA on Twitter and like TES USA on Facebook.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters