‘Imagine a world where teachers are held in the same esteem as lawyers and doctors’

Kris Boulton, teacher and blogger, writes:

I’m just a teacher, but as a teacher I noticed something early in my career, and I’d like to share it with you. People said I was brave, to become a teacher. Funny, I never really thought of bravery as a component of joining a profession. Of course I knew what they meant; Brett Wigdortz is the founder of Teach First, and in his book Success Against the Odds he describes Teach First’s strategy to “change the conversation happening on campus”.

He recognised that when someone talked to a friend about joining a teacher training programme, they’d receive a response: “Brilliant, you’re so brave!” Subtext: “What a weirdo. At least you’ll have good stories”. He wanted to change that response into: “Brilliant, you’re so lucky!” Subtext: ”****. I’m so jealous. You are one of life’s winners that I want to become”.

I used to think Wigdortz had been successful, that Teach First had indeed changed the conversation. In fact, I do still believe they have on campus but in the wider world, as I entered teaching, I realised there was another conversation taking place - people were debating whether or not teaching was a profession at all. Well, whether it is or it isn’t - or if it should or shouldn’t be - no-one can be truly convinced it’s a profession if that’s a debate that needs to be had, and it certainly is not a prestigious one. John Blake offers what is perhaps a more nuanced alternative: “Teaching is not yet a mature profession.”

I’m a teacher, and I’m not happy with that being the status quo.

What lawyers and doctors need to know

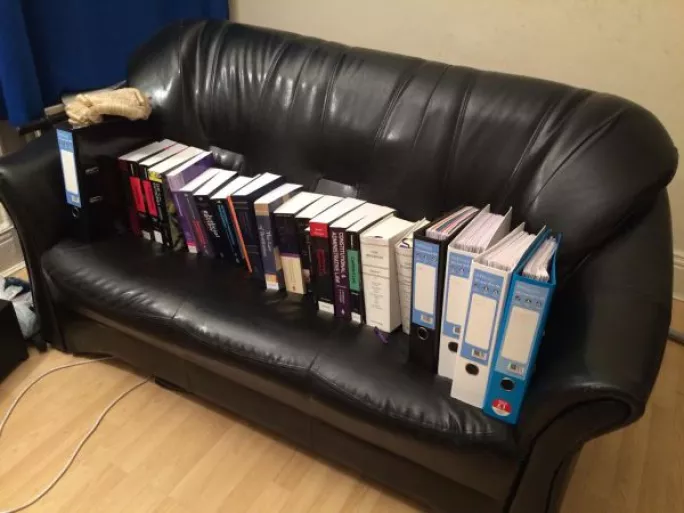

So what’s the problem, why are we not yet a mature profession? Well I live with two lawyers, who are now training to become barristers. I asked them to gather up all the notes and books they needed to know to qualify to enter the profession. Here it is:

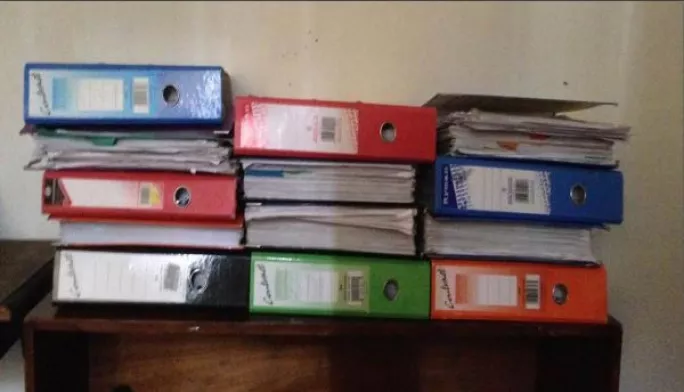

Another friend is three years into training to become a doctor. I asked him to do the same, and he sent me this picture.

As a teacher, you need to know this:

We never sat an exam to qualify for our PGCEs, and we were never given a body of knowledge like lawyers, doctors or accountants that we had to study. Yes there are textbooks, and yes there are the latest fashions and fads of teaching that we are made familiar with, but no real body of knowledge.

Once you can teach, you can teach anything

To illustrate that point further, in his recent book, Rob Peal describes a conversation he had with his headteacher when he visited his school in the summer before he was due to start training. “So Rob, what will you be doing over the summer to prepare for September?” “Well I think I’ll probably bone up on my knowledge of history,” he said. “Oh I shouldn’t worry about that! History is a skills based subject, you should be able to teach it without knowing any history at all,” was the reply.

Personally, I spoke with one headteacher who said to me: “I believe that if you’re a teacher, you can teach anything. All that matters is that you know how to teach.” All that matters is that you know how to teach. It doesn’t matter what you know about a subject, just that you “know how to teach”, and if I were to read between the lines, by that I suspect she largely meant “know how to manage a class of thirty kids”. What’s interesting here is that no lawyer is automatically assumed to be able to deal with any and all case types, just because they know “how to law”.

A Parent’s Perspective

Imagine you’re a parent - if you’re not - about to send your 11-year-old child off to secondary school for the first time. Imagine what it might be like to send this small person, whom you cherish more than anything else, into the care of strangers. You will abandon them for roughly eight hours a day, and trust that people you don’t know will take care of them in your stead. You will also trust that those people will educate them; teach them everything they need to know to leave school intelligent, and with an abundance of hope and opportunity ahead of them.

You might hope that they will return from school knowing even more than you do about various subjects, despite your decades-long head-start. What kind of teachers would the school have to employ for that dream to become a reality; for your child to out-perform you in their knowledge of mathematics, science, English literature and grammar, history and geography among others? How will you make sure in advance that the school employs teachers who do know more than you alone could teach your child?

It’s not possible to know what a teacher knows

Here’s an interesting open-secret: there is no way for you to know what your child’s teachers know about the subject they are teaching. Even if you had the time and the inclination, there is no book you can pick up, no resource you can interrogate that will tell you the minimum that every teacher of mathematics, or English, or science, must know in order to be called a teacher of mathematics, a teacher of English or a teacher of science.

When you go to a doctor or when you hire a legal representative, you know there is a minimum standard of knowledge they have been required to meet. You might not know what it is, and you might not have the time to find out, but you can at least rest secure in the knowledge that it’s there; and books documents exist that you could read to give yourself an overview of the kinds of things in which these professionals are assessed, to ensure they understand, before being permitted to call themselves doctor, or lawyer, or accountant. As a parent, you will have to trust to blind-luck that the teachers of your children know what they need to in order to best educate your child; not just to help them pass an exam, but to really educate them in their subject specialism.

A minimum standard

Of course, no matter the situation there will always be some natural variation. There will always be the doctors who are good, and those who are better; the lawyers who are good, and those who are better - this is not a call to eliminate variety in teaching or elsewhere, nor do I think we could succeed if we tried.

At this point, I’m simply acknowledging that there is a certain minimum standard, a bar set extremely high, that exists for other professions and that doesn’t exist for teaching.

A friend of mine has argued that I am wrong: such a minimum standard does exist. That minimum is guaranteed by our degree qualification. Not only that, but “subject knowledge” certainly is something that we are assessed for in becoming teachers.

Well, yes some of us do have relevant degrees, but not all. Some of us have A-levels studied a long time ago, and some others have neither degree nor A-levels. Some teachers have degrees or A-levels in one subject, but then find themselves teaching another, completely different subject. Yes, we may have degrees, and yes there is a box on a sheet that grades our subject knowledge as “inadequate, requiring improvement, good or outstanding”. We see it on observation forms, and we see it in termly reviews. So let’s look at how that system works at its very best.

I teach mathematics, and I have a 2:1 Masters level degree in physics, an almost entirely mathematical discipline. My subject knowledge is the only teaching standard that was and has been assessed as “outstanding” in every single observation or review I have ever had, right from the start. On paper - on paper - I think it would be accepted that I represent the highest standard of teacher subject knowledge, and now I hope that what I say next will dispel any hubris that might be connected to that statement, because what I’m going to do next is confess to you what I didn’t know.

I can’t stand here and list for you all the things about mathematics that I didn’t know, as I stood in front of a hundred hopeful children; there just isn’t time for that. What I can do though is give you a flavour, and hopefully some of these will be shocking, because it should be shocking for a maths teacher not to know these things:

- I didn’t know how to multiply decimal numbers.

- I didn’t know how to subtract numbers on paper. Actually I didn’t know many paper-based methods of calculation, including division and even long-multiplication.

- I didn’t know what number bonds were, or the hierarchy of strategies that exist for mental calculations

- I never realised that squaring a number was the same as actually constructing a square, hence the name!

And the list goes on...

I suppose a person might argue that I didn’t know these because I’d never used them; therefore they’d never been useful to me, and perhaps therefore they’re not useful for me to teach. To argue this is to be foolish.

I can recall a time I attended an assessment centre for a highly competitive and prestigious global consultancy firm, and during their quantitative reasoning test, which involved awkward numbers and no calculator, I struggled slowly using my sluggish, error-prone mental strategies while I was consciously aware of a girl to my left feverishly scribbling paper-based calculations using standard algorithms. Needless to say I didn’t even get to the second round of three. We can never know how our ignorance has held us back in life.

Furthermore, the more restricted the knowledge of our nation’s teachers, the even more narrow the minds of our future generations. Teachers should be trained to be the very most well-educated, knowledgeable professionals we have in our service, not left to wallow as classroom managers, with just the right amount of knowledge necessary to tip kids over a C grade in an exam.

Should teachers fear more rigorous assessment of subject knowledge?

By this point there’s a question that might have come to some teachers’ minds: should I fear what is being said? Is he trying to undermine my professionalism? Is he suggesting I’m not very good at my job, or not very knowledgeable? Is he proposing more hoops to jump through; more evaluations? Is he saying I should be licensed or struck off a teachers register if I can’t demonstrate knowledge of some esoteric part of my subject that I’ve never and will likely never need to teach?

Unequivocally, no, to all of the above.

Rather, if you’re a teacher, should not your knowledge and expertise be recognised, accredited and rewarded? Where there are gaps in your knowledge, shouldn’t you rest assured that your initial training will recover and augment all of the fundamental knowledge you require to deliver your subject, well, from the very first lesson? Shouldn’t you feel secure that there is an ongoing programme of professional development which will seek to further advance your subject knowledge? Shouldn’t there be ways for you to develop in the career you love, as a teacher, teaching children, rather than management being the only progression available to you?

What might a codified body of knowledge look like?

So what would it look like? I find that most people overlook the idea of actual “knowledge of the subject” of being a part of something teachers need to be taught; we all assume that a teacher with a degree, and having gone through school themselves, must know everything they need to know, or can easily pick it up again, and that we will insult them if we propose otherwise. I hope I’ve shown from my own experience that that assumption doesn’t hold - we really don’t know everything we need to, and we really do need to be reminded, or in some cases, even taught again, properly.

In fact, I’m going to allude to the former US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, in acknowledging that in the list I gave you there were some things I knew I didn’t know, “the known unknowns”, such as how to divide or subtract on paper, but more worryingly there were many “unknown unknowns”, such as the very existence of number bonds, or that Pythagoras’ theorem could be anything other than a formula for finding the length of sides.

Of course I do know these things now, but I’ve happened across them only through a combination of my own individual efforts, and random chance. I was never taught these things as part of any structured development, and I’m far from knowing everything I feel I need to be a confident, qualified professional, and the weight of the known unknowns bears down upon me, while I live in fear of just how many unknown unknowns might still be lurking out there.

There is no shame in admitting teachers don’t come to the table already knowing everything, rather it would be loopy vanity to think we do. Setting forth what we need to know in a subject, as a foundation, is a good first step. There are then many other pieces of pedagogical knowledge that fit around this. For example in my subject, maths, knowing that there are precisely four kinds of addition of fractions, and what they are, or knowing how different topics relate to one another, e.g. that similar shapes are enlargements of one another. Knowing the limits of complexity in question types that an “average” pupil should be expected to face, or knowing excellent and broadly-accepted ways of explaining ideas, or even what the most common misconceptions a child might face when encountering a topic for the first time.

Today, teachers teach what comes to mind, or what might come up on an exam. What if tomorrow, all teachers taught what they knew would best educate their children? Today, teachers are divided and fragmented. What if tomorrow teachers were united and unified? Today, teachers are isolated and pitted against one another in league table competitions. What if tomorrow, teachers were unanimous in how their subject knowledge should be passed to our future generation? Today, teaching is called a low-status profession, an immature profession, and sometimes not a profession at all. Well, what if tomorrow, teachers were respected and envied as an elite in our society? Highly competitive entry, highly-trained, highly-knowledgeable, on a par with doctors, lawyers and others. What if tomorrow the conversation we could all have is “Hi, nice to meet you, I’m a teacher” and the response we hear could be “Brilliant, you’re so lucky!” Subtext: ”****. I’m so jealous. You are one of life’s winners”.

This article is an edited version of a speech at Wellington Festival of Education

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters