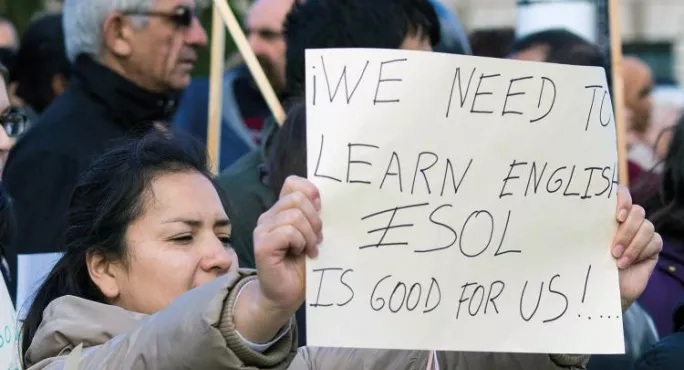

Immigration rules: Why Esol is more important than ever

Bound up with issues of immigration and integration, speaking English is seen by many as necessary to become British. The view that all people who settle in the UK should speak English is built into the new immigration policy as of January 2021. The policy extends the requirement to speak English to more arrivals than previously and, along with the end of free movement, is highly significant for the future for Esol (English for speakers of other languages).

New immigration policy, recovery from coronavirus and the new powers of devolved mayoral combined authorities (MCAs) to use government Esol funding more flexibly make it an opportune time to step back and consider the future for Esol in Britain. This is the backdrop to the Learning and Work Institute’s new report, Migration and English Language Learning after Brexit.

ESOL provision: new strategy needed to cope with demand

More: Why keeping Esol learners’ aspiration high is critical

Background: Esol students should be assessed by teachers, says Natecla

The rising demand for Esol provision

Colleges and community providers have consistently struggled to meet the high demand for Esol. This has been fed by high rates of immigration despite changes in migration patterns in recent years: while net levels from the European Union (EU) have fallen since 2016, the year of the Brexit referendum, they have increased from outside of the EU.

These changes are noticeable to Esol providers and have been accelerated by the pandemic, which has stalled and skewed migration in the short term.

It’s likely that more stable immigration patterns will emerge alongside recovery from the pandemic and from recession. All of these will affect future Esol demand in new ways.

As the economy recovers, demand for migrant workers is likely to rise, as it did after the economic crisis 10 years ago. But free movement from EU countries has ended so migrants arriving for work will need a job offer and, unless they are from English speaking countries, a certificate in English language at B1, intermediate level. There are some exemptions, including people on intra-company or global talent visas and people from Hong Kong.

Although migrants arriving on work-related visa routes will need to have intermediate level English, only 40 per cent of those who work, study or are accompanying family state employment as their main reason for learning. Some will still wish to learn English for general everyday purposes.

Other new arrivals will include people on family visas, and asylum seekers and refugees. All of these people will need to reach intermediate level Esol to gain the right to remain and citizenship, continuing to generate demand for Esol classes. New arrivals in these categories amounted to roughly 99,000 people in 2019.

In addition, there are already high levels of unmet demand for Esol, according to a recent report from the Department for Education. Future provision needs to address current outstanding needs as well as future demand.

There are likely to be significant numbers of new arrivals from Hong Kong: many will be proficient in English but those who are not may generate a demand for intermediate and advanced-level English classes.

Esol: why it needs to meet social and economic needs

The potential benefit of Esol to the UK economy is often ignored. Esol strategy needs to align with economic goals and, in particular, the UK’s agenda for skills. Too many migrants work beneath their level of education, qualification and ability yet the absence of workplace and work-related Esol makes progression extremely difficult. Esol could play a much more active role in addressing wasted potential and this should be part of the debate on social mobility.

Colleges delivering Esol should work with local stakeholders to plan provision that combines learning English with vocational skills at intermediate and advanced levels.

It’s easy to see the economic benefits of people arriving for work but these also apply to people from other entry routes. Eligibility for fully funded provision must be extended nationally, not just where MCAs can flex their adult education budgets. There should be a reduced or no qualifying period for asylum seekers and those arriving in the UK on family visas. New arrivals should be able to start learning as soon as possible. Early access to Esol is good for learners, and also brings wider social and economic benefits.

It is likely that people will continue to come to Britain to live and work, despite the end of free movement and new restrictions. Demand for Esol will therefore continue, though the balance between basic and higher-level needs may change, as well as the circumstances of learners. The sector, and policy on education and skills funding, needs to keep track of changing demand, and be ready to respond and to adapt.

Heather Rolfe is the director of research and relationships at British Future

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters