- Home

- A journey into ed-tech future

A journey into ed-tech future

I’m a busy teacher and often find myself working in challenging environments with challenging students. In many ways, this has shaped my underlying philosophy when it comes to ed tech as I’m heavily focused on the pragmatic, immediate side of what technology can offer: small-scale and utilitarian is very much my home turf.

It led me to wonder if, perhaps, I’d inadvertently developed a type of tunnel vision, concentrating on a surface-level usage and missing some of the deeper ways that ed tech can affect learning. My focus has always been on discussing the usefulness of technology in teachers’ daily lives, but this can be limiting.

So, I decided to take a different tack and an opportunity arose when Tes asked me to visit University College London and check out some of the weird and wonderful research linked to learning that is currently taking place there. Armed (ironically) with only a primitive notepad and an ancient Twin Peaks-era Dictaphone, I embarked on a whistle-stop tour of some of the cuttingedge projects that various teams were working on. Here’s what I learned.

Stage one

My first stop was the UCL Interaction Centre (UCLIC) lab, situated in the basement of one of the School of Engineering’s buildings (delighting the B-movie sci-fi fan in me). The centre focuses on exploring the links between people and technology, which is hugely pertinent to education, given the current focus in schools on STEM and computing.

The team and its head, Professor Yvonne Rogers, foolishly allowed me to play with some of the tech they have developed and, in return, I tried my very best not to irrevocably break it.

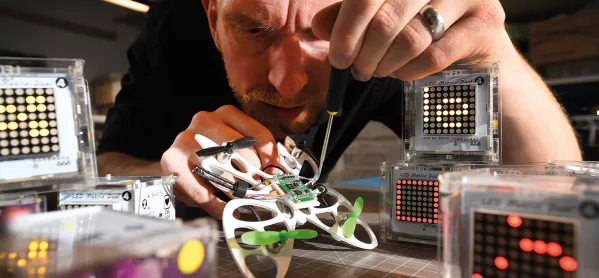

Something I was particularly taken with was the team’s Magic Cubes device - essentially a self-build computer kit that, when assembled by a child, takes the form of a box that you can hold in the palm of your hand. Dr Nicolai Marquardt, senior lecturer in physical computing, talked me through some of the thinking behind the project.

“We wanted to engage young children when it came to interacting with technology,” he said.

“What we decided to do was combine the making and constructing of the boxes, the activities [they can do] involving the various sensors and tools (LED colour lights, accelerometers, battery, processor, Bluetooth) and elements of coding.”

It was this combination of elements that I found fascinating. There’s often a compartmentalising of skills that goes on in schools in reference to technology, but, with the Magic Cubes, the team has developed a crossover learning tool that encompasses different facets of engineering and computing and is wrapped up in a child-friendly package - one that already has an inbuilt element of success that pupils can achieve simply by putting the thing together in the first place. It then moves on to more advanced skills and different contexts.

“A lot of the time, what we get from the children is that it does translate this abstract idea of coding into the physical world and they find that very engaging,” said Dr Susan Lechelt, research associate in the UCLIC Department of Computer Science.

“Tactile” is not necessarily a word that I automatically associate with computing, but after pouring coloured light from one Magic Cube to another, stretching to put it in corners of the room to try to gauge the temperature and rebuilding one after carelessly knocking it across a work surface, it’s the term that has stuck with me.

It is the thought process, the melding of different ideas using technology as the catalyst, that I find hugely appealing. It is, admittedly, a step beyond the way that I often think about technology in the classroom. Before floating off to my next stop, I had two more things to see.

The first was a drone used in the Drones for Good project, headed by Dr Richard Milton and Dr Flora Roumpani of the UCL Centre for Advanced Spacial Analysis (CASA), which employs the gadgets coupled with mapping technologies - that communities pilot over rapidly expanding urban areas in Lima, Peru - as a starting point for discussion and involvement in planning processes.

The second was the VoxBox, a charmingly physical machine that looked like the result of Willy Wonka getting his hands on random bits of IKEA furniture and using them to gather questionnaire information using all manner of buttons and levers.

Alas, my enjoyment of both was briefly hampered by the fact that I had to shamefully beg the team for a pair of triple-A batteries as the ones in my Dictaphone had, of course, taken it upon themselves to die. Technology: not always a marvel.

Stage two

So, with new batteries inserted, I headed to the UCL Knowledge Lab, and to the office of Andrew Burn, professor of media education, who explained to me a number of projects that he and his team have been working on.

“One is this software that was developed as a game authoring tool for schools. The original idea was to teach kids about game design in the context of media studies and technology, and I became interested in how it related to storytelling,” he said.

As an English teacher, and (slightly) reformed video game addict, Burn immediately piqued my interest.

Video games as a vehicle for narrative is something of a focus for me as a teacher in alternative provision. I sometimes use it as an “in” with my students who often have low levels of literacy and little access (and, if I’m being completely honest, interest) in more traditional forms of fiction.

Burn continued: “We’ve created a project with the British Library where we’ve repurposed the software using Unity (game engine software) to create a game-authoring program based on the manuscript of Beowulf.” Yep. I was hooked.

After a fast, simple and intuitive five minutes of top-down drag-and-drop mapping and adding of characters (including our big boss, Grendel), Burn, with a mere click on the keyboard, transformed the former 2D map into an impressively rendered 3D environment and proceeded to usher me around dank caves, interacting with characters from the text (who can be coded to speak in the original old English or have user-created audio utter from their mouths), all the while explaining the benefits of such a game.

“We extended the coding interface so the kids can learn about Boolean logic, which is linked to the computing curriculum, but the big idea is to try to connect up the arts curriculum (particularly English literature) with computing, which are two areas that don’t normally speak to each other at all.”

Much like what I saw in UCLIC, there’s an attempt to try to cross-pollinate different subjects. I asked Burn why he views this as important. “I don’t necessarily think of them as disparate,” he said.

“A text like Beowulf, which began as an Anglo-Saxon poem, was studied by Tolkien and used as a basis for The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, which then generates tabletop games, which in-turn generates modern computer role-playing games. There’s a very strong connection there.”

It was this “wider” style of thinking that I repeatedly come across during the day and it represents something very different to the compartmentalised, stripped-down way I think about tech. I asked Burn where he visualises the starting point for a game like this in schools; does the story come first, or the technology?

“It’s highly dependent on context but, ideally, it might get English teachers thinking about programming and computing teachers thinking about narrative,” he said.

The game is highly adaptable in both its user interface and possible uses in schools. As a teacher of English, I’m sometimes hesitant about moving away from a text in order to teach it, but in my own context I can see, with students who otherwise may be disengaged, something like this working well.

Also, as I’m in further education and often think about vocational usage, it’s a wonderful way to peer behind the curtain of game design and realise the many strands that go into creating a compelling gaming experience, as it emphasises the partnership of game design and high-calibre storytelling.

After failing abysmally to slay a dragon, I popped downstairs to check out what was probably one of the most technically impressive projects I’d seen on my visit.

Stage three

Playing the Archive is an attempt to digitise and archive 20,000 accounts of play and play equipment for children collected by folklore experts Iona and Peter Opie during the 1950s and 1960s. An impressive feat in itself, but it was one of the strands of the project that most stood out for me.

“We’ve been through the generations of this, we’ve digitised the pages, we’ve made 3D scans but they still look like objects in a case with labels underneath them,” said Burn. “So how can we really engage?”

The answer for Burn and the team is to use virtual reality to create an immersive environment that will let users experience the games that were documented more than half a century ago.

“It’s so today’s kids can play the games of their grandparents,” said Burn. “And also the grandparents can play the games of their grandchildren.”

I’ve talked about the scope of VR in the pages of Tes before. For me, it’s a technology that offers a wide range of possibilities but one that I fear won’t reach its potential. Playing the Archive seems to be an idea that is pushing the envelope of the technology and the imagination needed to do something original and culturally important.

As Dr Valerio Signorelli, research associate at the UCL CASA, demonstrated some of the mapping tools, responsive virtual environments and options that are available to create these immersive environments using 360° cameras, directional sound positioning and other modelling programs, I was once again struck by another unusual blend.

In this case, it wasn’t a cross-curricular one; it was one of nostalgia going hand in hand with high technology.

From a teaching point of view, the ramifications of being able to experience, on some level, a playground of the past is a step towards an immersive history. Not one of kings and queens but a history that is close, shared and intimate - enabled, somewhat ironically, by cutting-edge advances in technology.

After that came a pair of fascinating discussions: the first with Professor Sara Price, a reader in technology-enhanced learning at the UCL Knowledge Lab, regarding the Move2Learn research project.

This will explore how museum exhibits can encourage movement that helps children develop their scientific thinking through analysing the importance of gesture. The second, was with Dr Mutlu Cukurova, a learning scientist at the Knowledge Lab, who is researching the use of camera tracking of effective collaborative work through the recording of non-verbal interaction, which would allow teachers to gauge who is and isn’t struggling.

And then the cameras tracked me out of the room and to my final destination.

Stage four

To end my visit, I tried to sew together my experience by questioning Professor Carey Jewitt, director of the UCL Knowledge Lab, about what I had seen.

I put it to her that although technology is being utilised in some fascinating ways, from what I had witnessed, it’s the ideas that seem to come first.

“Our focus is on communication, interaction and learning, it’s not on technology,” she stated.

“We’re interested in how technology remediates the way in which people learn but we’re not interested in technology for technology’s sake.”

We went on to discuss some of the things that I’d witnessed in terms of the implementation of technology in a mainstream setting, and how, often, it is shipped in without forethought.

“What we talk about here quite a lot is the ‘grammar of the school’ and that schools are really interesting places that have rules and practices and very long histories,” she said.

“There is little point in taking a technical innovation and plonking it in a school when you haven’t really talked to teachers or learners, or the people in control of that environment, to really understand what they need.

“One of the questions we ask ourselves is ‘how can we harness technology, not for disruption but for enhancement?’ ” she added. It was the last sentence that I found familiar as it reflected my own personal ethos when it comes to technology.

But as I made my way to King’s Cross to hop on the train back to Leeds, I came to realise something: enhancement through technology can mean different things to different people. For me, it means grabbing something, shaking it about a bit to see if I can get any use out of it and then chucking it if I can’t or using it if I can. It’s a reactive, perhaps slightly manic, approach.

Yes, it might be the result of my work history but that doesn’t automatically mean that it’s the best way of doing things.

What was made clear to me talking to people about the projects that they are involved in is that there’s another version of enhancement: one that is more considered and perhaps doesn’t rely on immediate benefits.

Instead, it looks for different ways of doing things, coupling elements that perhaps might go against the grain, all to achieve outcomes that are not immediately obvious. It’s enhancement through thinking deeply about technology and the ways it can help learning, teaching and education in general, not just in the day to day but in the long term.

Will I ever get to the point where I use technology for enhancement like that? I’m not sure if I’ll get the chance. But to be honest, I find it heartening that there are people who do. It’s certainly inspired me to have a think about digging down from the surface in regards to ed tech. And maybe replacing that Dictaphone.

Tom Starkey teaches English at a college in the North of England

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters