- Home

- ‘One-dimensional interpretations of Timss and Pisa shouldn’t distract from their genuine value’

‘One-dimensional interpretations of Timss and Pisa shouldn’t distract from their genuine value’

Take one knotty education challenge and three expert consultants. Everyone knows you will almost certainly find five different opinions.

Fortunately, education research rises above the cut and thrust of passionately held opinion and brings an element of objectivity to the discussion. Doesn’t it?

What are we to make of this week’s the release of the latest findings of the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) study, just one week after the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (Timss)?

Both are international studies which, every few years, aim to measure the performance of education systems worldwide.

Both estimate an overall achievement score in science and mathematics (among a range of other outcomes).

Both employ sophisticated statistical techniques to generate robust estimates whilst minimising the disruption and cost associated with testing large numbers of children.

Yet, despite these similarities, for many countries the two studies tell rather different stories. For example, whereas Northern Ireland does extremely well at maths in Timss (much better than England), its Pisa maths scores are much less impressive (and no different from England’s).

How can we explain these apparent contradictions, and do they undermine the value of the international studies?

Not necessarily. The two studies ask different questions of education systems and so inevitably give slightly different answers.

For example, Timss includes students in Years 5 and 9 in England (aged 9-10 and 13-14), sampled from classes in those year groups, whereas Pisa focuses on 15-year-olds.

In the case of Timss in Northern Ireland, where only 9-10 year olds participate, Timss therefore explores primary phase education whereas Pisa focuses on the secondary phase.

Another important difference is in the subjects considered: Timss only measures maths and science achievement (and is complemented by a separate study - Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), whereas Pisa also covers reading literacy.

However, even if we narrow our comparison solely down to considering the maths and science achievement of 15-year-olds in Pisa and the maths and science achievement of 13-14 year olds in Timss, we still see a varied picture.

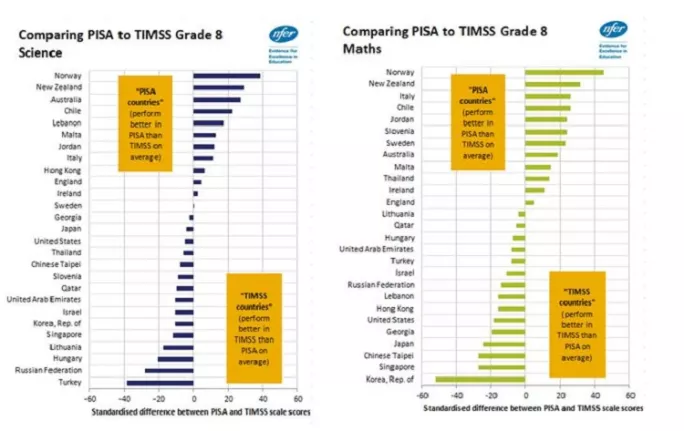

The following two charts show the difference between the Timss and Pisa scores achieved by countries participating in both 2015 studies.

The two studies measure achievement on different scales, so the size of the differences are adjusted to centre around zero (most countries’ raw Timss scores are higher than their Pisa scores, but this is just like the difference between using Centigrade or Fahrenheit to measure temperature).

Countries towards the top of the charts, such as Norway, New Zealand and Chile, have relatively higher performance in Pisa compared to their performance in Timss.

Countries at the bottom of the charts, such as Singapore, Korea, Turkey and Russia, perform relatively more strongly on Timss. England lies in the middle of the two groups, with the relationship between our performance in Timss and Pisa close to the average for both maths and science.

These groupings contain diverse sets of countries, for example among the latter group in science, Singapore achieves the highest scores overall in both Timss and Pisa, with its advantage in Timss simply being even greater than in Pisa.

Turkey, on the other hand, performs poorly in Pisa but achieves a more favourable score in Grade 8 Timss. However, what they share in common is an education system that seems to perform better according to Timss than to Pisa.

These differences could still be due to the different cohorts tested, each of whom may have experienced recent reforms in their countries to differing extents. However, there are also a number of other important differences between the two studies which are likely to be relevant.

Most notably that Pisa seeks to test students’ ability to apply knowledge to novel contexts whereas Timss is more curriculum focused. These findings therefore do not only reflect the performance of different education systems, but may also reveal as much as the priority each places on different aspects and aims of learning.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which is responsible for Pisa, inevitably focuses on the importance of education in contributing to economic performance. Timss is run by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), and has a much longer history rooted in the education research community.

It is easy then to see how advocates of particular policies or classroom practices are able to find whatever they want in the findings. What this analysis demonstrates is that an overly simplistic interpretation of the results from Timss and Pisa risks seeing only one part of the picture.

One-dimensional interpretations of Timss and Pisa should not distract from the genuine value they hold. At its best, this value comes in enabling nations to obtain a more objective measure of their educational performance, jolting many among the political classes out of complacency.

It comes from generating hypotheses on effective educational approaches, which can then be investigated using complementary research; and comes from creating a global education community where competing ideas can be debated, scrutinised and applied to the ultimate benefit of young people.

For England, the messages from Timss and Pisa are consistent - our performance is moderate and stable.

In looking for solutions from other countries for how we might improve our performance in future, we will do well to consider both studies as the start of a conversation, not either one study as the final word.

Ben Durbin is head of international education at the National Foundation for Educational Research

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters