Opinion: The maelstrom of change or an education clusterf**k? You decide...

Here are a few thoughts from the first part of my presentation at ResearchEd, Glasgow. It seeks to give a wider perspective on the context in which any changes, including becoming more research-informed, will need to be rooted.

A “done-to” profession?

We are on the cusp of something in education. I just can’t make up my mind whether it is a total disaster or the kind of interface maelstrom that occurs as you move from one paradigm to another. It’s confusing, and confusion always creates uncertainty. Some people go into their shells, as others see an opportunity to seize the initiative. My sense is that many people are feeling “done to” rather than done with or done by at the moment. I’ve no empirical evidence, just a gut feeling. Too many dictates by political or school leaders, timescales that are ridiculously short, and a lack of listening and debate, all of which are unhealthy and unhelpful.

Overall, the English education system is good - but it is stuck and still too variable. The variability links to the relative underperformance of children from more disadvantaged backgrounds. We all want a good or better school for every child but outside of academic achievement we have limited agreement what this might look like, how we could measure it or how to achieve it.

Assuming we have enough teachers, the critical issue moving forward will be one of teacher agency. A commitment to greater subsidiarity, from both political and school leaders, and increased responsibility for and by teachers are key. The opportunity and ability to be more self-directing could lead to a sea change in education.

Being more informed through research, data, feedback and experience will require a change in the way schools operate. Any change in culture will be impacted on by the autonomy granted, accountability, metrics chosen and used, demographics, workload and the effectiveness of professional development available.

Incomplete and confused autonomy

With the introduction of more academies and free schools, there is a much greater structural autonomy: a freedom from local authorities. The freedoms tend to be much less if you are a sponsored academy and possibly matter little to the teacher in the classroom. Being freed from ties to universities in delivering initial teacher education is a mixed blessing and breaks a potentially useful long-term alliance in initial and ongoing teacher development. It also presents the opportunity for the most advantaged schools to get stronger through taking the cream of new entrants to the profession each year.

Alongside more welcome freedoms for schools by the removal of levels, there is a counterbalance in terms of a national curriculum, examination syllabuses to follow and politicians’ tendency to use forceful accountability levers to impose their own pet project, be it the Ebac or phonics. There is still too little sense of autonomy being felt in schools or class rooms.

Accountability gone mad

Ofsted, mocksteds, performance management and performance-related pay have all produced a generation of professionals with cricks in their necks. Too many people, particularly those working in disadvantaged communities, have been looking over their shoulders instead of at the children in front of them. The interesting - or maybe frightening - reality is that there is little or no evidence I know of that would conclude that these have a significant or substantive impact on improving the quality of education. There are likely to be far better ways to invest the finite amount of time teachers and leaders have at their disposal, as well as their increasingly limited financial resources.

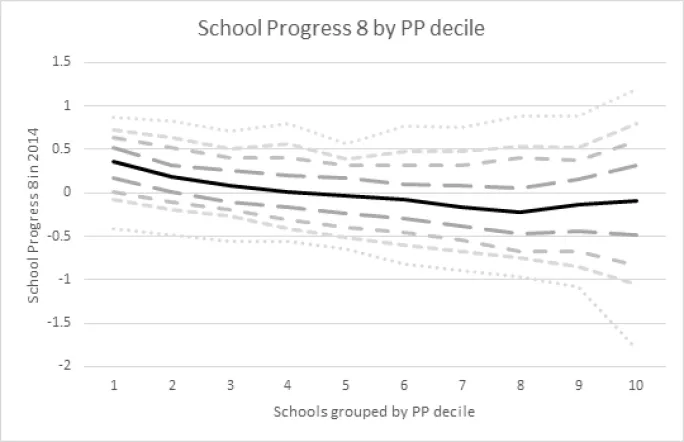

The pupil premium is a good idea. However, at a time of increasing costs and fixed budgets, there is a real danger it will be partially or largely subsumed into budgets to prevent schools plunging into deficit. This won’t serve some of our most disadvantaged pupils, but the problem is even deeper than that. The current accountability system works against schools in the most disadvantaged communities as the metrics used tend to underplay the valuable work they are doing across the board. Their relative disadvantage in attainment measures is obvious but the graphic below shows the negative impact on schools’ Progress 8 measure that have large numbers of children who attract pupil premium funding.

Credit: Dr Becky Allen of Education Datalab

Demographic time bomb: recruitment, retention and admissions

The next decade will see about a million more children and young people in our schools, the baby-boomer generation of teachers and leaders retiring, and a demographic dip in young people moving through secondary schools leading to a reduced pool of potential graduates from which to recruit teachers. With an improving economy, graduates will also have a greater number and variety of opportunities presented to them. You may have already noticed a number of politicians criticise individuals and unions who dare to mention the looming crisis as being overly negative and unhelpful. Their message is a bit rich given the battering schools, their leaders and teachers have taken from politicians over the decades. The ability of schools to retain sufficient teachers is the predominant element of the problem and more directly in our sphere of influence. The uncomfortable reality for political parties is that they are part of the problem and are unwilling to make the changes required to help stem the flow. Equally, school leaders don’t always help themselves and, consequently, their schools.

Workload Challenges

The timetable for concurrent curriculum change across the whole system will create a workload issue that no number of working parties will be able to overcome. There is simply too much for teachers to do in terms of continually planning and replanning curriculums, which will squeeze almost everything else to the margins or out altogether. This is in addition to the concerns expressed by teachers about the impact accountability and marking has on their time. Some of this is a necessary part of the job, but it has been taken to excess over the years.

There are still many activities that schools currently do that could be abandoned. Top of my list? Performance management, performance pay, mocksteds and Ofsted - in no particular order. With so many important things we could focus on and do, they would all struggle to justify their place in a future education system where time and resources were plentiful. With austerity about to hit schools and workload pressures mounting, these undertakings take on a futility that we would be better without.

Pointless data collection by teachers and on teachers

Letting go of levels was painful to begin with. They were introduced the year after I started teaching and I had experienced a nearly 30-year love affair with them. Having looked at how we had contorted them beyond recognition and possible alternatives, I wouldn’t go back for all the tea in China. The data leviathan has to be tamed. Hopefully schools and their leaders will use this as an opportunity to totally rethink how often whole-school data (data that isn’t focussed on the interface between the teacher and learner) is collected. Once or twice a year would be my opening bid; it would make the every six/eight weeks model so prevalent in schools currently look very silly and wasteful.

Similarly, the data we have been collecting on teachers for decades in terms of lesson grades is already disappearing. My beautiful colour-coded spreadsheet will soon be just another museum exhibit to our collective stupidity. Similar to life after levels, we need to know what each teacher is good at and what they need and wish to improve. From this, the genesis and route of improvement becomes more obvious. Knowing what staff are good at also means you know who can help.

Professional development focussed on competence and coverage rather than excellence and impact

The professional development diet for teachers has often been driven by generic whole-school needs or perceived priorities. Some teachers have been accepting of this and have attempted to implement it within their classroom. Others have been physically present at the training, but absent in mind and spirit. The TNTP Report released in early August, The Mirage: Confronting the Hard Truth About Our Quest for Teacher Development came to some uncomfortable conclusions about teacher professional development in terms of impact and excellence. Too few teachers understood the need to improve and the system doesn’t know how to help them.

“But school systems shouldn’t give up on teacher development. And they shouldn’t cut spending on it, either. Rather, we believe it’s time for a new conversation about teacher improvement-one that asks fundamentally different questions about what great teaching means and how to achieve it.”

TNTP report, The Mirage: Confronting the Hard Truths About Our Quest for Teacher Development

Teachers who improved did so despite the system, not because of it. A teacher’s willingness to improve seemed to be the key, which takes me back to an early point around teacher agency as a key element of our future education system. It’s maybe time to redirect our efforts, resources and thinking to reimagine teachers’ professional development.

Embedding research within schools needs a fundamental culture shift that sees the classroom as the key structure within the system, the student-teacher interaction as the critical interface and effective professional development of teachers as the primary area for leaders to influence.

Too much of what we do isn’t great. Some of it isn’t actually even very good. You may currently feel like you are swimming against the tide, but remember: the tide always turns.

This blog has been reposted (with permission) from an original post on Stephen’s Leading Learner blog. You can also follow him on Twitter @LeadingLearner.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters