- Home

- Stephen Tierney: Why Ofsted’s new framework won’t work

Stephen Tierney: Why Ofsted’s new framework won’t work

Ofsted is beginning to give us an insight into its forthcoming new inspection framework. While there is much to commend, what is being suggested around the curriculum in particular will, I fear, allow the continuation of a high stakes, cliff-edged inspection process and do more harm than good.

It is proposed that from September 2019, a new Quality of Education judgement will subsume the current Quality of Teaching, Learning & Assessment and Outcomes judgements and be extended to include curriculum.

The curriculum element has already been widely signalled as a three-stage process:

- Intent: what is it that schools want for all their children?

- Implementation: how is teaching and assessment fulfilling the intent?

- Impact: results and wider outcomes that children achieve and their destinations.

There is talk of conversations with teachers as well as leaders as part of the inspection process but these will inevitably be limited. It is worth remembering that these conversations will happen during a one- or two-day visit every four years. Inspectors spending extra time on site will be minimal; that’s assuming Ofsted’s budget isn’t further cut, it can actually retain sufficient inspectors and its remit isn’t expanded or reprioritised.

Conversations are part of a narrative, not a scoring system. When I heard in June 2018 that Ofsted would be retaining its four-point grading process, I knew the whole much-lauded venture could be doomed. Grading the intent, implementation and impact of the curriculum is hugely problematic in terms of reliability unless you focus on the impact (results element). A better alternative would be to lose the grading system and instead develop a narrative-based report. This could add to the development of the curriculum as part of an ongoing low-stakes continuous improvement process predominantly owned by the school.

Helping schools in disadvantaged areas

A further concern must be that a preferred Ofsted curriculum will emerge through the inspection schedule, inspection reports and “beliefs” of school leaders and teachers about what Ofsted want. The next chief inspector may well be faced with the curriculum equivalent of when Sir Michael Wilshaw felt obliged to publicly state that Ofsted "has no preferred teaching style": as it stands, the EBacc is already topping the list of Ofsted requirements with its adverse impact on the arts, design and technology.

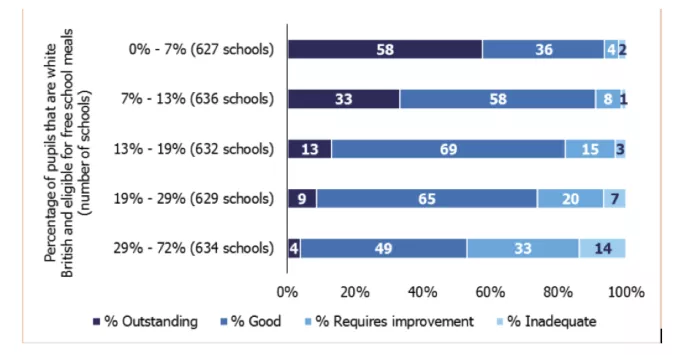

We are being told that the new inspection framework will be “particularly helpful for schools and colleges and other providers that serve more disadvantaged areas”. It certainly can’t get much worse than it already is, as evidenced by Ofsted’s own analysis (see graph below).

The assertion that, “shifting our [Ofsted’s] focus away from outcomes in isolation, we should empower schools to put the child first and make teaching in high disadvantage schools even more rewarding”, when read alongside “that doesn’t mean there will be no link between what we find about the quality of education, and what the published data says. They are, one hopes, somewhat correlated” is problematic. Whilst we continue with uncontextualised progress scores schools in disadvantaged areas, serving pupils predominantly from white British backgrounds, will continue to be savaged. The lack of understanding by Ofsted about teaching and leading within our most disadvantaged and challenging communities seems to be profound.

Ofsted’s senior leaders are on record about how standards, based on examination results, will apply equally to all pupils. Schools working in disadvantaged areas have a massively high bar to get over whereas those in more advantaged areas have a more limited challenge. This makes the suggestion about how disadvantaged areas will benefit from the new inspection framework unrealistic. We need to see senior leaders at Ofsted fundamentally rethinking their views on contextualisation of data in order to develop metrics based on school effectiveness rather than a school’s intake.

Workload and the recruitment and retention of teachers have featured heavily as Ofsted talks up its new framework. Some of the claims about how the new framework would address these problems seemed more wishful thinking than realistic solutions to the difficulties the profession is facing. The recent National Foundation for Educational Research and Nuffield Foundation report, Teacher Workforce Dynamics in England, shows the adverse impact on the retention of staff in a school that is graded "inadequate". Teachers and leaders in these schools are far more likely to move from the school and leave the profession; significant turbulence in staffing is not a strong foundation for improving a school.

The basic flaw in the current and proposed frameworks is the retention of the two distinct elements of inspection: “as a simple means to gather the necessary information to make a judgement about a school” and “as a means to help schools to do their job to the very best of their capabilities”. Teachers know formative and summative elements of assessment don’t work well together; the grading always trumps the feedback.

Talk about the problems caused by the current inspection framework shows little realisation that each framework brings its own problems; this one will be no different. Some of us have been through multiple framework iterations as Ofsted continually tries to reinvent itself.

We now need a blank sheet of paper on which to fundamentally reimagine what a regulator can contribute to school improvement. It will need to be an independent and far-reaching piece of work as we currently have no coherent theory of change around school improvement in this country. Only then will we really address the issues of workload, retention and recruitment of teachers and raising the standards of education across the country.

Stephen Tierney is the CEO of the Blessed Edward Bamber Catholic Multi-Academy Trust, and was previously a secondary headteacher for 14 years, chair of the Headteachers’ Roundtable and author of Liminal Leadership. He tweets at @LeadingLearner

*Quotes are taken from HMCI Amanda Spielman’s speech to the Schools NorthEast summit on 11 October 2018

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters