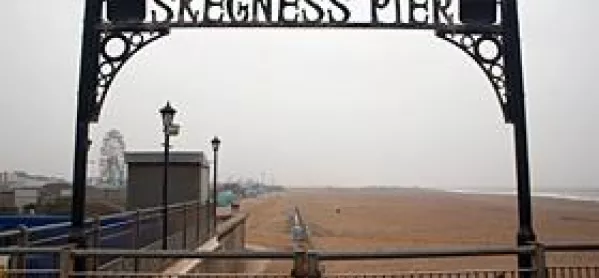

Waiting for a sea change

As the two-carriage diesel train wheezes across the flat Lincolnshire landscape, it is easy to see why Skegness is rarely visited by national politicians or journalists.

A three-hour rail journey from the capital, this seaside resort on the North Sea coast is unlikely to be the location for a government policy launch.

In summer, thousands of people still flock to the old-fashioned attractions of its funfairs, arcades and beach, and the town is better known for its “So Bracing” slogan and its large Butlins holiday camp than for educational excellence.

Indeed, when the ice cream sellers have flown south for the winter, the isolated resort’s economic and educational challenges are all the more apparent.

Because of the resort’s seasonal, low-wage economy and transient population, some parts of the town and surrounding areas have become associated with poverty and educational underachievement.

In Ingoldmells, to the north of the town, 45 per cent of children live in poverty, a figure on a par with parts of inner-city Glasgow, Liverpool and London. Several other wards have levels of up to 30 per cent, well above the national average. Aspiration is traditionally low for young people, who are growing up in a town where 39 per cent of the workforce have no qualifications at all.

Local newspaper reports indicate that jobs at Butlins - the town’s largest employer - are sought after, but there is competition from Eastern European workers, too.

To make matters worse, educational opportunities in the area have been limited for generations, with many young people facing the unattractive prospect of 5am starts to attend distant FE colleges in Boston and Lincoln.

Taking into account all of these factors, it should come as no surprise that local secondary schools once had some of the worst GCSE results in the country.

Influx from the cities

“The problems here are exactly the same as in the inner cities,” says Sue Roy, principal of the Skegness Infant Academy, which is part of a local group of four recently converted primary academies and a secondary academy sponsored by Greenwood Dale Foundation Trust.

“Many children come in with low personal, social and emotional skills, and we have to provide a very rich language environment to make up for the family conversation they are not getting at home,” she says.

She explains that many of the problems in the town are exacerbated by the influx of poor families from the cities of the East Midlands, who decide to stay in the area once their holidays are over.

“They give up their council accommodation back home and come here, expecting to be rehoused by the council here. Of course, they are at the bottom of the list and end up in places such as bed and breakfast accommodation,” she says.

The schools employ a family support worker to help parents with a range of issues, such as learning to deal with bad behaviour and bonding with their children. Some parents - little more than children themselves after teenage pregnancies - need particular support.

Emma Hadley, executive principal of the academy group, adds that issues around mobility, transience and poor attendance are key to educational underachievement. She estimates that about 30 per cent of students at Ingoldmells Academy (a primary) live in caravans.

“We have children in our primary academies in Year 5 who have been to eight different schools when they arrive. They have suffered frequent breaks in their education,” she says.

Hadley explains that the seasonality of employment means that at Skegness Academy around half of students in Year 11 have joined the school after Year 7. Forty-five per cent are eligible for the pupil premium.

Despite these many challenges - and against a background of Lincolnshire’s divisive grammar school system - the school has achieved impressive improvements in recent years. At Skegness Academy’s predecessor school, St Clement’s College, just 5 per cent of students achieved five A* to C GCSE grades including English and maths in 2007, the year it launched.

By 2010, just before it relaunched as Skegness Academy, this had already risen to more than 36 per cent. Last August, the figure hit 51 per cent - although this is still 8 per cent below the national average. However, results at the Skegness Grammar School next door have fallen gradually over the past four years, from 97 per cent to 79 per cent.

Skegness is far from alone in the challenges it faces. Many other isolated seaside towns suffer the same problems to a greater or lesser extent. A map of the areas of the country where students are doing better or worse than should be expected of them, given their backgrounds and prior test results, shows that London, the focus of politicians’ attentions for some time, is now doing rather well.

The flip side is that the number of old-school seaside resorts underachieving is striking: Scarborough, Clacton, Margate, Ramsgate, Hastings, Torbay, Ilfracombe, Blackpool and the whole of the Isle of Wight, for example, along with many others.

The issue was raised most recently by shadow education secretary Stephen Twigg in a speech at the House of Commons late last year. Bemoaning the “arc of underachievement” in coastal towns and some northern cities, he called for a series of regional versions of the City Challenges that ran in London, Manchester and the Black Country under Labour. He said his party would investigate refunding the tuition fees of trainee teachers agreeing to work in northern and coastal towns for at least three years.

“Ten years ago we were talking about underachievement in London,” Twigg said. “With London Challenge we saw a significant change. London went from one of the worst areas to the top. The Manchester Challenge saw significant progress and Liverpool Challenge saw progress, too. We need to learn from that.”

But he stressed that we should be “extremely careful not to apply big-city solutions” to more isolated parts of the country where opportunities for collaboration are more difficult to come by.

“But if you take most coastal towns there will be schools doing more well or less well (who can collaborate),” he added. “And with modern technology we can have a school collaborating with other schools in different parts of the country.”

Twigg said the issue in coastal towns is “more complex” than simple academisation: something the current government is pursuing with full force. Indeed, as in much of the rest of the country, academisation in deprived and underperforming coastal towns has been intense. In Torbay, for example, all three comprehensives have converted to academy status in the past year. Torquay Community College, now Torquay Academy, has even entered into a multi-academy trust partnership with Torquay Boys’ Grammar.

Recruitment challenges

One of the most notorious problems for schools in seaside towns, which are geographical “dead ends”, is staff recruitment. In Skegness, Hadley believes that groups of primary and secondary academies working together under a single “brand” can significantly alleviate this.

Traditionally, she says, it was not unusual for Skegness schools to receive just one or two applications for teaching posts. But being sponsored by Greenwood Dale Foundation Trust gives a wider range of opportunities for in-house promotion and for staff to work across a number of schools. The schools also now have the resources to offer better continuing professional development programmes that enable them to “grow their own” staff, she says.

“These are attractive prospects for talented and ambitious teachers and could not have been offered by the individual schools before,” she says.

As if to prove, however, that academisation is not necessarily the answer, the pound;30 million Marlowe Academy in Ramsgate, Kent, which replaced the failing Ramsgate School in 2005, was put in special measures after an inspection in November 2011.

Other attempts to address coastal underachievement in recent times include the expansion of the Future Leaders and Teaching Leaders programmes to towns along the South Coast. These schemes take highly motivated, talented staff and develop them for leadership roles in schools in disadvantaged areas.

But experts say more needs to be done to address further and higher education opportunities. This could make coastal towns more attractive to investors by providing a more skilled workforce and halt the “brain drain” of high-flyers to the cities.

One expert on coastal communities, Professor Steve Fothergill of the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University, highlights the success of the branch of the University of Brighton in Hastings. Applications from students hoping to study there from September are up 25 per cent on last year.

“One of the big issues in seaside towns is the outward migration of better qualified people. If you want to be a merchant banker, you won’t get a merchant banker’s job in Skegness,” he says. “This is in contrast to the inward migration of relatively poorly qualified, low-wage people looking for cheap, private rental accommodation.

“If you have a big enough town to support it, introducing higher education would enable brighter kids to stay local.”

In small-town Skegness, the chances of a university setting up shop are slim, and local FE provision comes in the form of a branch of the Lincolnshire Regional College.

Skegness Academy has stepped into the breach by hugely expanding its sixth-form provision. It expects 350 students to study in its sixth form in September. The academy offers A levels and BTECs, and a full-time “director of careers” ensures that - officially at least - nobody leaves school with Neet (not in education, employment or training) status. Head of careers Elizabeth Draper says the school’s “zero Neets” status is achieved through “badgering” of less motivated students who might fall off the radar.

Rather than being let out on to the street with nowhere to go, students who are not ready to move on are invited to stay on in “Year 14”, an extra year to prepare for jobs, training and further study.

All this is well and good, but politicians and campaigners have insisted that the problems in coastal towns cannot be resolved by some energetic academy schools, an outpost of a former polytechnic and the odd posh art gallery. Many seaside towns are beset by levels of extreme poverty that have to be addressed before any genuine progress can be made.

Extreme poverty

Labour mayor of Skegness Mark Anderson says that government cuts will only make things worse for educators.

“We have children coming in to our primary schools who have mental health problems, parents on benefits, poor accommodation,” he says. “We have children coming in to school with hypothermia; they haven’t had breakfast.

“There are very low wages and a huge amount of need for social housing, but no housing is being built.”

He says the area will be disproportionately hit by the changes to disability living allowance, the benefit cap and the introduction of the so-called “bedroom tax”: “Things are just getting worse.”

Professor Carl Parsons, author of Schooling the Estate Kids, a book documenting the story of Ramsgate’s troubled Marlowe Academy, agrees that poverty is at the core of educational failure. And government policies forcing schools to push students down academic routes that are inappropriate to them add to the problem.

Parsons, a former director of education at Canterbury Christ Church University, says: “We kid ourselves that the way out of the problem is better schools and school improvement strategies and better teachers, while we do nothing about poverty.

“At Marlowe Academy, kids are measurably behind at 5. We need a holistic and more generous approach to the children of the area.”

Many seaside towns face the same issues as the inner cities - they can suffer similar levels of poverty and educational disadvantage. The solutions may not be exactly the same: Skegness is not Hackney and Margate is not Islington. But considering the past five years, it looks as though the political will is there to change things, at least. The future for schools in seaside towns will certainly be interesting. Bracing, even.

Photo credit: Paul Floyd Blake

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters