- Home

- Why teachers must remember your students are not your children

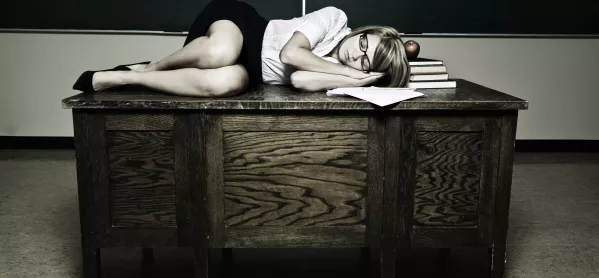

Why teachers must remember your students are not your children

Whatever colour your collar, most teachers would like to think of themselves as professionals. There are around a dozen trade unions representing teachers and their leaders in the UK, plus the relatively new chartered college of teaching and a small army of other “professional” associations or societies teachers can join if they wish.

Many will spend their entire career within the confines of the schools in which they work, with occasional contact with these organisations, but without any opportunity to work with lawyers or accountants, marketing professionals, technologists or engineers. They have no opportunity to compare professional behaviour or practice, and it shows.

Something which always struck me as unprofessional, even as a young teacher with no other experience, was the ease and frequency with which teachers criticise the school they work for. Even the professional language of teaching reflects this, with teachers referring to working in the trenches or on the frontline, as though they were squaddies and anyone without a full teaching timetable a tyrannical officer. These kinds of unhelpful lines are drawn early in every teacher’s career. They persist into leadership and even beyond.

Compare that to the multi-national I worked for where no one would ever dream of bad-mouthing the company, even on a Friday evening in the bar after a tough week. It would have been considered a crime against your colleagues, an unthinkable betrayal of joint purpose.

And it all starts with teacher training. Whether in the primary or the secondary sector, the training teachers receive simply doesn’t help them develop the same kind of professional mentality and attitudes common in other professions.

How many teacher training courses, for example, start by detailing the variety of organisational structures any teacher will find themselves playing a crucial part in, once they take up a full-time role in a school? How many teachers reading this genuinely understand how the school they work in is managed? Will they understand the difference between governors and managers, between executive responsibilities and non-executive, how a board differs from a leadership team? How often are vital professional concepts like compliance or accountability fully explained to trainee teachers?

I can recall a meeting with the head of a London academy in which it quickly became apparent that he did not understand the governance relationship between the school he led and the trust it was just one part of. When people don’t understand who they are really working for, or the processes that hold that organisation together, it’s no surprise professional attitudes suffer.

Basic finance and budgeting are more knowledge I would expect to see on every teacher training course. So much stress and irritation in schools would simply disappear if this happened. Textbook publishers stopped sending sales staff into schools with inspection copies when they discovered most teachers were buying textbooks on one principle only: more of what they had already. How many departmental heads in secondary schools buy books only when the school reminds them of the deadline to spend their budget?

One wonders how many recent financial scandals in academies might have been avoided if anti-corruption and fraud legislation were a core part of teacher training. From experience, I can definitely say this might prevent ex-teachers who find themselves procuring a commercial contract from asking bidders if there might be a job for them, were they to award them the contract. Something that’s completely against UK and EU anti-corruption legislation. In fact, the law states that if anyone does make such a suggestion, you’re breaking the law yourself if you don’t report it to your own manager.

If this kind of genuinely professional knowledge was embedded in teacher training, two things, in particular, might change, which would have immense benefits for teachers, schools and children. People, from government down, who think it’s perfectly OK to exploit teachers’ high levels of intrinsic motivation by asking them to work for free, might stop. And teachers themselves would shake off the wholly unprofessional idea that it’s somehow their duty or responsibility to work every hour God sends, step into every breach and fulfil every societal role others are only too eager to stand back and watch them fulfil, out of the generosity of their hearts.

One of the wisest pieces of professional advice I’ve ever heard was offered to me when I was the kind of young and childless teacher who volunteered for everything: “Remember, they’re not your children.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters