Schools are on the financial brink - and it’s going to get worse

The phrase “cost of living crisis” first entered the political sphere in September last year, when shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper used it to describe the “triple whammy” of bill rises, tax hikes and benefits cuts facing families across the UK.

Since then, the term has been used more than 400 times by MPs in the Commons, with the rise of the energy price cap, high rates of inflation and soaring fuel cost rises all contributing to a squeeze on purse strings that has hit the lowest paid the hardest.

But, while the recent response to the crisis has rightly centred on how it affects individuals, organisations have also suffered. Schools, in particular, have been hit hard.

Not only are schools dealing with many of the same issues affecting individual households, but they are also struggling with the long-term financial effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, schools face their own “cost of living crisis” this spring - a crisis that has now coincided with ambitious targets set in this week’s Schools White Paper.

- Budget 2021: Covid catch-up fund boosted by £1.8bn

- Cost of living: Teachers ‘using food banks’ as cost of living crisis hits

- Related: Heads’ leader warns ministers a new funding crisis is ‘looming’

“There just seems to be so many plates we’re juggling, and we’re not quite sure what the next plate that comes along is going to be,” says Pepe Di’Iasio, headteacher at Wales High School in Rotherham, and president of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL).

It’s a sentiment shared by headteachers and school business managers, who say that rocketing gas and electricity bills, rising catering and building prices, and sustained high supply cover costs are combining to make them fear what Hayley Dunn, business leadership specialist at ASCL, calls a “perfect storm of financial pressure”.

“Many of the issues facing household consumers, such as inflation on day-to-day items like food and rapidly increasing energy prices, will also be significant concerns for business leaders at schools,” says Dunn, adding that heads will be “seriously concerned” about the potential implications for already tight budgets.

Energy crisis

The most immediate problem is the rising cost of energy. Back in January, Tes reported that some schools were seeing their bills rise by more than 100 per cent.

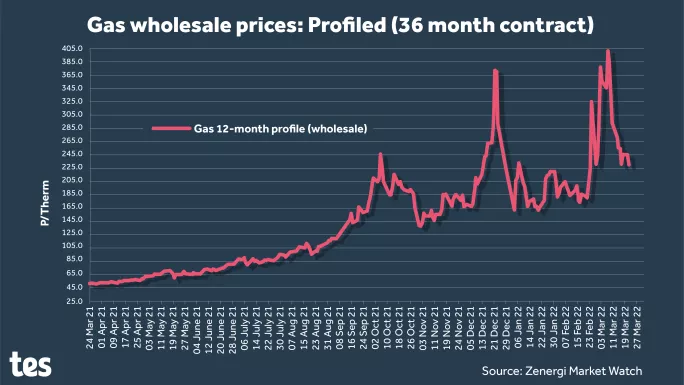

In February, we followed this up by revealing that the wholesale element of a typical three-year fixed deal for schools had risen to nearly 200 per cent higher for gas and 150 per higher for electricity on figures from a year ago.

The corresponding figure for the end of March was more than 200 per cent for electricity and more than 270 per cent for gas, according to data from Zenergi, an energy procurement company used by around 3,000 schools.

Many local authorities have told Tes that their energy frameworks - which their maintained schools are on - run in line with the financial year, which runs from April to April. Clearly, many schools will be renewing at the worst possible moment.

Nottingham City Council told us its prices would go up significantly now its fixed-term deal has expired, while Walsall Council will be hit with a similar hike.

But the issue isn’t limited to local authorities. The Confederation of School Trusts (CST) says that, while some academies are on deals that expire at the end of the academic year, many have tariffs that follow the financial year, generally as a legacy of the agreements they had when they were part of a council framework.

Indeed, Pepe Di’Iasio’s school, which is a standalone academy in South Yorkshire, will see annual costs go up by just under £100,000 this month, alongside many other schools in the area that purchase their energy together as part of a joint procurement deal.

Chris Parham, headteacher at St Issey Church of England Primary School - which is part of a multi-academy trust - in Cornwall, says bills at the school will rise by 190 per cent for electricity and 450 per cent for gas in April.

“This is more than we dreaded it would be,” he says.

Covid fallout

These rises come on top of an already perilous financial situation. Supply cover, for example, is now putting a significant strain on budgets.

Obviously, schools have been dealing with teacher absence for close to two years now, and have planned (as far as this is possible) for it in their budgets. But, as we approach spring, absence remains high and, if rates are sustained at this level, it could start to cost more than the reasonable worst-case scenario planned for by business leaders.

“We have peaks and troughs with sickness and you expect it to be higher in winter, especially with Covid, but when you’re heading into summer, it tends to be that there isn’t so much illness,” says Hilary Goldsmith, a school business manager at a secondary school in Kent. “But who knows now? We’ve still got high numbers of people isolating and off, doing the right thing. You kind of have to budget everything for a worst-case scenario,” she adds.

Similarly, Robin Bevan, headteacher at Southend High School for Boys, says: “I think we all anticipated extra supply costs in our budgets, but we all thought Covid would be over by different points. Even now, it’s still affecting our school significantly.”

Heads fear Covid will impact schools for some time yet. One junior school head says his supply cover budget is already up 400 per cent for the academic year. Speaking in late March, Bevan says he has six staff off.

“Just to put that in context, my usual figures are less than one day per person per year,” he adds.

The government’s workforce fund, which supported schools facing staffing challenges during the pandemic - or at least those that fit the scheme’s rather narrow eligibility criteria - closes on 8 April. Yet, midway through last month, there were still as many as one in 10 teachers off work.

Recruitment struggles

Short-term absence is not the only worry, though: losing staff permanently and not being able to recruit replacements is becoming more prevalent than it is usually.

Bevan tells of a “progressive erosion” of teacher morale that, he believes, may come to a head as schools begin to return to some semblance of normality.

“I’m looking at a group of high-quality teachers who have gone above and beyond over the past two years and are beginning to think ‘this ain’t worth it’,” he says.

He says he’s advertised three jobs in the past few weeks and has had just one applicant for one, and none for the others.

The sentiment is echoed by Goldsmith. She says that, throughout the pandemic, teachers were running on “adrenaline” and that “Blitz spirit” but adds that many who have been holding on tight will start to come to realise that they’re “exhausted”.

She says: “I’m predicting we’ll see burnout and staff on the top of their game not being able, or willing, to stay. Normally you can plan your staffing budget because you know who’s going to retire, who’ll be moving on, and it’s really hard to predict those things at the moment, assumptions just don’t exist now.”

This will be a particular worry for schools given recent data on teacher recruitment, with a report last month showing targets would be missed in many subjects. This could see fewer early career teachers (ECTs) in the system, and thus increased staffing costs for schools.

Inflation impact

If all this were not enough, rising costs associated with inflation, which the Bank of England has warned could rise to 8 per cent this year, coupled with supply chain issues linked to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, are also hitting budgets hard.

One way in which schools are being affected is via their catering costs. The Lead Association for Caterers in Education (LACA) - the professional body representing catering managers - says that members across the school food sector have been facing challenges around rising costs for several months, and it expects the situation to become more difficult.

Russia and Ukraine supply almost a third of the world’s wheat exports, meaning wheat prices are now at record highs, while Ukraine is the largest exporter of sunflower oil in the world. This, combined with high inflation and rising energy and fuel prices, is affecting operating costs.

In terms of how this is directly affecting schools, it generally appears that those with in-house catering are worst affected. Di’Iasio says that catering costs at his school have risen by around 10 per cent in the past few months, and could well get worse.

“We’re having to look very carefully at the menu that we offer. Our chef and accounts manager are looking very closely to make sure that we can provide good value for money, as much as we can for students. This is at a time when good free school meals are absolutely vital for our students,” he says.

The cost of building and repair work is another issue that is keeping school leaders awake at night. ASCL’s Dunn explains that many schools put major capital rebuilding or refurbishment projects on hold during the pandemic and could see their costs rise “exponentially” as a result of a “worldwide shortage of materials and inflationary pressures”.

James Butcher, director of policy at the National Federation of Builders, says that the construction sector is currently “under immense cost pressure”, with products and materials inflation running at over 20 per cent.

He also says that the industry is experiencing its highest vacancy rate since records began in 2001 and that the combination of these factors means schools will likely find contractors only willing to hold prices for a matter of weeks, making budgetary certainty for longer-term projects difficult.

Goldsmith agrees that the issue is affecting schools. She says: “We bounced a lot of building work down the road because of Covid, so there’s more to do. And if you delay work, it becomes more expensive because there’s more damage to pick up.

“Costs have gone up as well and there are more schools that want the work done. There’s the market rate issue that comes in - if everyone wants builders, then they’re going to put their prices up.”

Stormy weather ahead

Just to add another factor into the mix, Di’Iasio points out that damage done by a series of storms over the winter has forced schools’ hands in some regards - he says his school has had to have work completed due to damaged roofing.

“It’s hard to get the contractors in at the right time because they’re literally washed off their feet, but then things like timber costs have increased massively. We also pay at the sharp end because contractors know we’re anxious to get the work done, and resources for the world are at a premium,” he adds.

So, what’s the result of these issues? And what are schools doing to try to combat the deluge of financial challenges being flung their way?

Stephen Morales, chief executive at the Institute of School Business Leadership, says that school business leaders will balance the books, as that’s their job, but he says the DfE needs to acknowledge that this comes at a price.

“That price is that it’s going to constrain schools’ ability to tackle the widening attainment gap. The recovery process from the pandemic is going to be slower if cost pressures are high: if we’re not supporting staff with investment and pay rises in line with the cost of living rises we’re seeing, we’re going to be haemorrhaging them. In addition, the situation also limits the repairs they can make to their crumbling estate,” he says.

Heads have talked about decisions they are already starting to make.

Chris Parham says a need to find £3,000 in his budget this academic year, and more next year, due to rising energy prices and the April hike to national insurance contributions - which the government says was covered by an uplift to the core schools budget in last year’s Spending Review - means he won’t be leasing a minibus for his small rural primary, as previously planned.

“We’re paying through the nose to do travel with coach companies to go to the nearest town to go swimming, for example, and without being able to afford this minibus, that’ll not continue”, he says.

“There’s a cultural capital element to this as well. Kids who have already missed out on certain trips and experiences during the pandemic will miss out on more things as a result”, he adds.

Pepe D’Iasio says that the uncertainty has already meant he’s held fire on hiring to replace a member of teaching staff that is leaving his department due to relocation. He wants to wait until the effect of another budgetary issue - staff pay rises in future academic years - is clearer.

“We would normally go to replace that member of staff right now,” he says. “Instead, what we’re doing is holding fire on that, because what we prefer to do is make that decision when we’re more aware of what our budget might look like in September, and then decide whether we can actually afford it.”

‘Profound issue’

Robin Bevan agrees that cutting staff costs sometimes seems like the only answer. “If you’ve trimmed all of the areas of expenditure that you possibly can - and, as a head, I hold my hand up and say we have done that: we recently had one of the school resource management advisers visit us, and there was nothing in any of the obvious places - your only other option is to reduce staffing.”

But he immediately shuns this idea. “It’s absolutely the wrong thing to do. The Department for Education has been championing workload reform. We’ve got a profound issue in recruiting staff, we’ve got a profound issue in retaining staff across the system. Then your only solution to an inadequate model is to make the situation worse? No headteacher should ever be in this position.

“You should always be in the position to staff your classrooms with the level and expertise you need, and have something left. If what you’re looking at is nothing left, or indeed a deficit, then the failing is not in the school, the failing is in the adequacy of the funding that’s come from central government.”

So why does the DfE think schools have the resources to cope?

The DfE previously told Tes that, in 2022-23, core schools funding will increase by £4 billion compared with 2021-22 - giving a 5 per cent real-terms per-pupil boost - and this will help schools to meet wider cost pressures.

Some doubt has been cast over the likelihood of this, however, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies projecting that spending per pupil in 2024 will be at about the same level as in 2010, as it fell by 9 per cent in real terms between 2009-10 and 2019-20.

The DfE has also dismissed some of the issues facing schools with regard to energy, saying that “inflation in this area would have a relatively small impact on a school’s budget overall”.

Bevan thinks that the problem is partly how the DfE examines the financial position of schools.

“The DfE seem obsessed with assessing the financial health of the school system by totalling everybody’s position,” he says.

“You can’t assess the financial health of the system by looking at the total in the system. It’s the same as saying there isn’t any poverty in a country by looking at its overall wealth. The issue is clearly about how it is distributed.”

And Stephen Morales agrees, saying: “There will be regional pockets where things are OK. It does vary - that’s why a national picture, perhaps in some ways, isn’t that useful.”

So, is there any hope for schools that are struggling? Morales says he thinks schools will cope with the pressures but doesn’t expect anything extra in terms of DfE support.

“I have no expectation of the government doing anything different. If you’re asking business leaders to balance the budget, we’ll do that. And where efficiencies can be identified, we’ll find them. But what they need to do is decide what their priorities are. If education is not a high enough priority, don’t be surprised at what you get - a slower pace of recovery than we hoped for.”

With a mention of education or schools notably absent from last month’s Spring Statement, and ASCL general secretary Geoff Barton expressing his concern that schools are facing a “fresh funding crisis”, Morales’ cynicism appears well placed.

What’s more, in an exclusive Tes interview preceding the launch of the Schools White Paper this week, education secretary Nadhim Zahawi said he was certain that schools have enough money. So certain, in fact, that, when devising the White Paper - which set targets many would argue require substantial investment - he didn’t ask for any more money from the Treasury to fund it.

The comments many school leaders may have made when reading that interview may be unprintable, and the effects of the decision are being felt by some already.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article