The recent Ofsted news about inspecting safeguarding and its offer to revisit schools after three months to see if improvements have been made brought to mind a quote from business management guru Patrick Lencioni: “Most leaders prefer to look for answers where the light is better”.

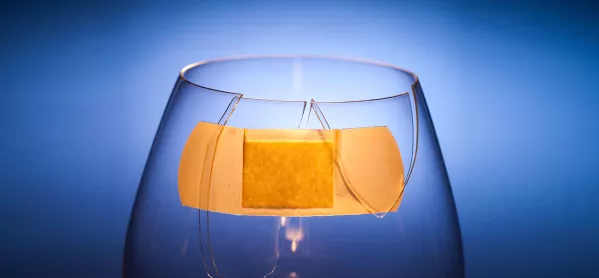

In essence, it is easier to look at compliance than look at culture. But this is merely a sticking plaster approach to improvement that does not get to the root cause of the problem.

While it is good to see Ofsted consider how it can improve its inspection processes, the solutions put forward to address the concerns around how safeguarding is inspected are not fit for purpose and will end up doing more damage than good.

The specific concern with what they have proposed relates to a system that will offer to revisit a school after three months if they were graded “inadequate” overall owing to ineffective safeguarding, but all other judgements were “good” or better.

Ofsted changes:

The promise is that if in those three months a school has resolved the safeguarding concerns, it should see its overall grade improve.

This set-up would likely involve a set of compliance-based actions issued by Ofsted inspectors to the school to complete before the revisit.

This is where the key concern exists because a compliance mindset in relation to safeguarding is destined for long-term failure. It will focus on a select few people working on directed tasks to solve in a short window of time - rather than developing the professional judgement of colleagues to make best-interest decisions for every child.

That will only exacerbate what was likely at the root of the “inadequate” rating in the first place: school culture.

Because if safeguarding is not effective, the issues will not be rooted in compliance and fixed through some document policy wording change or small process issue, but in culture - and three months is not enough time to fix school culture so that safeguarding is foremost in everyone’s thoughts and actions.

Furthermore, without cultural change, any claimed improvements in safeguarding effectiveness will be a short-term illusion gained through ticking a set of boxes to satisfy the regulators to change a one-word judgement - at the expense of leaders truly developing their professional judgement, safeguarding and leadership expertise.

For leaders, this also adds yet more potential stress as there will be an implicit expectation on headteachers and designated safeguarding leads (DSLs) from governors and trust boards to turn things around within three months.

This places more, not less, pressure on leaders to improve safeguarding at pace because they will be desperate to show that they have made the necessary changes while having no hope of embedding them in the normal working practice of the school community within that short window.

It would take a serious level of bravery from a leadership team to push back and rebuild culture as the priority rather than moving into the tick-box compliance mindset.

Moreover, I would argue that an Ofsted-backed compliance-driven approach could be problematic to colleagues who are trying to lead safeguarding strategically. The work to ensure safeguarding is effective is never done. An Ofsted grade captures a moment in time. A strong culture of safeguarding ensures that every decision is in the best interest of the child. It ensures longevity of good decision making for children.

In September, Ofsted has promised guidance on effective and not effective safeguarding practice. My fear is that an examples-driven approach to safeguarding best practice puts even more emphasis on ticking boxes and being compliant. The consequence is that task-based directives for improvements neglect the culture and leadership that enabled the best-practice examples in the first place. I hope I am wrong.

However, given that before they have even released this handbook one of the main proposals they have announced after so much public scrutiny is nothing more than the intention to give schools yet more compliance measures to follow, I am dubious this will be the case.

Sarah is currently the director of safeguarding at Archway Learning Trust after leading safeguarding across two national trusts previously. From September, she will be taking on the role of executive director of safeguarding and wellbeing at CORE Education Trust