Why arts subjects were hit so hard in the pandemic

Last month, data from the Office for National Statistics revealed something surprising about how lockdown had affected learning: while all subjects had seen a decline in the amount of content taught, art and design subjects appeared to be disproportionately affected.

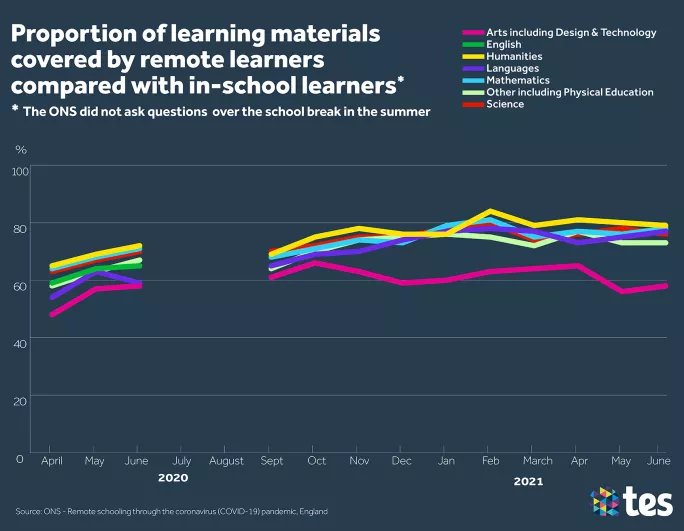

Specifically, between April 2020 and June 2021, an average of just 60 per cent of the learning material received by in-school students was successfully delivered to remote learners studying what the ONS classed as “arts including design and technology”.

This compares with 73 per cent of the maths and science curriculum, 72 per cent of English lessons, and upwards of 70 per cent for other subjects.

The best-performing subject area was the humanities, on which remote learners reportedly received 76 per cent of the learning that in-school students received.

Not only this, but whereas the other subjects all showed marked improvements over the course of the pandemic as teachers learned to adapt to the unusual circumstances - both teaching remotely and in class - art and design subjects have struggled throughout.

For example, for May and June 2021, the amount of material covered for remote learners was as low as 56 and 58 per cent respectively for arts subjects, compared with 79 per cent for humanities and 78 per cent for mathematics.

It’s a striking set of figures that point to a real challenge for catching up students across the range of subjects in the category, which includes the likes of music, drama, design and technology, textiles and food technology.

Where the data came from

This is certainly not good news for teachers and subject heads in these areas. However, it is first understanding a little about where the data that paints this picture has come from.

The first thing to note is that the numbers above are not a measure of student attainment.

They are a measure of hours of teaching delivered by teachers and, surprisingly, they were not collected primarily for the education sector but because of how Britain’s GDP is calculated.

“GDP requires us to know how many hours of education are being delivered at what cost,” explains Laura McInerney, CEO of Teacher Tapp, the survey company the ONS enlisted to help.

The problem was that, with the onset of the pandemic, it was no longer clear how much teaching was actually being delivered. And the ONS quickly realised the challenge this creates if we want an accurate model of economic performance.

“They found themselves with a problem because they could no longer presume that the pay bill divided by teachers’ standardised working hours was what was happening,” she says.

That’s when the ONS turned to Teacher Tapp to understand more about what was happening on the ground.

The way Teacher Tapp works is that every day at 3.30pm, teachers on the app receive a push notification with a handful of survey questions for them to respond to.

The ONS told Tes the question asked for this data collection was: “Thinking of students learning remotely today, to what extent did they have learning materials enabling them to cover the same content as pupils who were learning in school?”

Teachers were then presented with options ranging from “To a great extent” to “Not at all”, and the ONS put numbers on each option. The midpoints were then used to calculate the scores above.

For teachers, the quickfire questions provide an unweighted snapshot of opinion from their professional peers, akin to a Twitter poll. But for clients like the ONS, the data can be weighted and spliced in more granular ways.

For example, of the 8,000 to 9,000 responses TeacherTapp expects to receive on any given day, they know which key stage the respondent teaches, the subject they teach and other demographic data. So, responses can be weighted using the school workforce census collected by schools to ensure the sample is representative.

“People often survey teachers, which is also what we do, but if you don’t know lots about them, it doesn’t really tell you a lot,” adds McInerney.

The reality of teaching arts remotely

So, that’s how the numbers were arrived at and, whether or not you agree with the methodology, the figures certainly seem to match anecdotal accounts from teachers in arts and design subjects.

“Lockdown was an absolute nightmare,” says Hetty Hughes, head of drama at a boys’ school. “Our remote provision was very much ‘watch this, respond to this, research this…’ [as] you can’t really do anything remotely practical on [Microsoft] Teams.

“I think most schools tried to follow a timetable similar to what they would have had in school,” she explains, “[but] it became apparent that wasn’t going to work.”

Peter Simons, director of music at Boothroyd Primary Academy, is another to admit that moving to teach arts online in the pandemic was not easy.

“Remote teaching was difficult, especially in schools like mine where we have a curriculum designed around learning to play a musical instrument in each year group.”

This meant, for example, he had to ask pupils to use pots and pans as musical instruments and then try and coordinate listening to them play this on video - something that did not really work that well.

“When teaching [remotely], I had to make sure everyone’s sound was off at home as the software could not cope with anyone else playing other than myself,” he says.

“Therefore it was impossible to correct errors as I couldn’t hear what they were doing and the lag of the small picture was not helpful.”

This lack of equipment and space in which to work with it was also a big problem for Steven Berryman, who oversees music, drama and dance for two schools in an academy trust.

“The key thing is all these subjects rely on specialist spaces,” he says. “We rely on being able to put students in groups to do creative work, and suddenly you can’t collaborate. You’re not working in groups, you have to work individually.”

This also perhaps explains why the gap in learning level between art and design and subject areas such as humanities has remained so far apart throughout the past 18 months: no matter how good teachers got at teaching remotely, if pupils do not have the tools or right spaces at home the lessons can never match being in class.

Another issue was that with everything closed, teachers were unable to augment their teaching with any trips to theatres or museums - something that Tom Campbell, chief education officer at Greenwood Academies Trust, said had a big impact.

“As a trust, we were concerned throughout the lockdown periods about both the impact of pupils not having access to the usual classroom arts activities as well as the closure of arts and cultural institutions and events across the country,” he said.

“We felt the impact of being unable to continue our massive programmes of trips and visits, of which there are hundreds across the trust over the course of the academic year.”

Primary problems

What’s more, it appears from further research by the National Foundation for Education Research that there has been a particular issue with how primary pupils were affected by this, with many moving to secondary with a real gap in their knowledge.

NFER research director Caroline Sharp says that it appears a big part of the issue is that arts-based subjects were not given the same focus as usual.

“[A] study that we’ve done recently indicates that schools were very concerned about numeracy and literacy in particular as you would imagine, and some schools have prioritised time for that,” she says.

“It’s possible that may have played into it, as they might have insisted on those things and perhaps less so the arts activities and so on.”

Hughes says this definitely chimes with her experiences with younger learners, with many lacking confidence in arts and design subjects on arriving at secondary school.

“Generally when they come in in Year 7, they are really enthusiastic, really want to get involved,” she says. “This time, there are some like that, but in general, there’s a big unwillingness to do anything in front of other people.”

Berryman raises this concern too around music lessons: “If you’ve just had a whole year when that child hasn’t sung with others, they probably haven’t sung on their own,” he says.

“They haven’t had the chance to play classroom instruments as typically in the curriculum.”

Catch-up strategies

So if we know this issue exists, what can schools do about this so students can catch up on the lost learning in arts and design subjects?

Well, of course, there is catch-up funding available, and in Hughes’ case this has been used to pay for students’ access to an online theatre platform with thousands of pre-recorded performances.

But Hughes is also keen to get back to taking her students to visit the theatre too: “We need to get them back out doing that, because that’s a cultural-social thing as well,” she adds.

Campbell also says that focusing on providing arts-related opportunities outside school has been a big driver for their work since returning to reinvigorate pupil engagement in these areas.

“As we began to emerge from lockdown, the trust prioritised reconnection for our pupils. To help tackle this challenge, we sought out partnerships with other organisations who could support what we are trying to do for our pupils.”

This has included partnering with everyone from the Royal Shakespeare Company to Youth Hostel Association and local councils doing everything from performing plays to visiting heritage sites and museums.

Meanwhile, Sharp and her colleagues published their own research paper, based on conversations with headteachers and senior leaders in a number of schools, looking at four models that schools are employing for catching students up.

One interesting area from this that has come up is to take a blended approach in which subjects are combined, such as having students in an art class paint something relevant to the history curriculum or linking maths in design and technology lessons - an example cited in the NFER’s paper.

“[One setting] ran a whole-school DT week, which they used to develop maths skills including spatial awareness, rotation and shape. There had not been time to develop these skills within maths lessons, because teachers had spent much time helping pupils recover core number skills,” it reads.

“This strategy had been developed to enable pupils to develop critical maths skills, while working on an extended DT project.”

Beyond these ideas, though, it seems the main thing for many is to strive to deliver as much of the curriculum as possible, whenever possible: “It’s even more marking than before, more feedback than before, more after-hours clubs,” says Hughes.

Berryman agrees that now is the time to double down on a commitment to the arts: “We certainly haven’t changed our curriculum, we’ve not made any reduction, we’ve not cut things out,” he says.

He says this is crucial not just to help close any learning gaps but also to ensure that the power that the arts can have for children is central to their school experience and wider wellbeing - an issue from the pandemic that the arts may be especially suited to help tackle.

“You need to maintain the integrity of your curriculum, keep it broad, make sure there’s space for children to be involved in the arts because singing with others, performing with others, dancing with others, painting, drawing...all these activities are the perfect outlet for a child who’s probably been working alone for a considerable amount of time.

“Creating things together is going to be the most valuable thing for their mental health and to reconnect to their communities as they return to school.”

James O’Malley is a freelance writer and tweets @Psythor

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article