Are school improvement officers now just education folklore?

They are the experts who thousands of schools should be able to turn to for support on teaching and learning, staffing and behaviour.

And they are the public servants with the crucial role of ensuring that the majority of England’s state school system is performing to the highest possible standards.

But a Tes investigation reveals that the country’s all-important army of local authority school improvement officers is fast vanishing, leaving increasing numbers of heads with no one to turn to.

The findings suggest that three-fifths of these jobs across the country have gone in just six years. Figures obtained from more than 60 local education authorities show that the number of school improvement officers employed by them has fallen from 1,568 in 2010-11 to 629.2 in 2016-17 - a drop of 60 per cent.

The responses to Tes freedom of information requests also reveal that spending by the councils on school improvement has been cut in half from £141 million to £71.5 million over the same period.

This has created a situation in some authorities where teams with just a handful of people in them are responsible for the performance of more than 100 schools.

That new reality for maintained schools relying on local authorities for school improvement support is in stark contrast to what the government wants to see for academies.

Academy trusts should run no more than 12 to 20 schools to be in the best possible position to drive improvement, academies minister Lord Agnew said last year.

Today, in some areas, a single council employee can be responsible for twice that many schools on their own. Ian Linsdell, headteacher of Poplar Street Primary in Audenshaw, Manchester, summed up the situation at a recent summit when he said the school improvement team in his district “could fit in one car”.

Much of the rhetoric of school reform in recent decades has been about freeing schools from local authority control. But on the ground, many heads, in the majority of state schools that lack academy status, say they have depended on rapidly shrinking local council school improvement teams for support, analysis and guidance.

Money’s too tight

Clem Coady, headteacher of Stoneraise School, a primary in Carlisle, warns that the cuts to these officers mean the education system is losing local expertise and experience, which is undermining efforts to drive up standards.

“What was so important was that your school improvement [team] knew their schools,” he says. “They knew about the locality, the challenges you face and the journey you have been on. Now, if you broker someone at £300 or £450 a day, you have to spend the first few hours explaining all of that.”

Coady says that is the reality for many schools now - that if they need support they have to buy it in, from already overstretched budgets. “We really needed some behaviour support recently,” he says. “We thought about bringing someone in. But our budget is so tight we just couldn’t afford it.”

Judy Shaw, headteacher of Tuel Lane Infant School, in Sowerby Bridge, West Yorkshire, has similar concerns.

“The old model of every school having a school improvement partner who was employed by the council is something that I used to really value,” she says. “They would come into your school every term to look at what you were doing. They would report back to the council, but it was constructive conversation. They were someone heads could turn to.

“It’s something I miss but I guess a lot of the schools who went on to be academies decided they would be better off going it alone.”

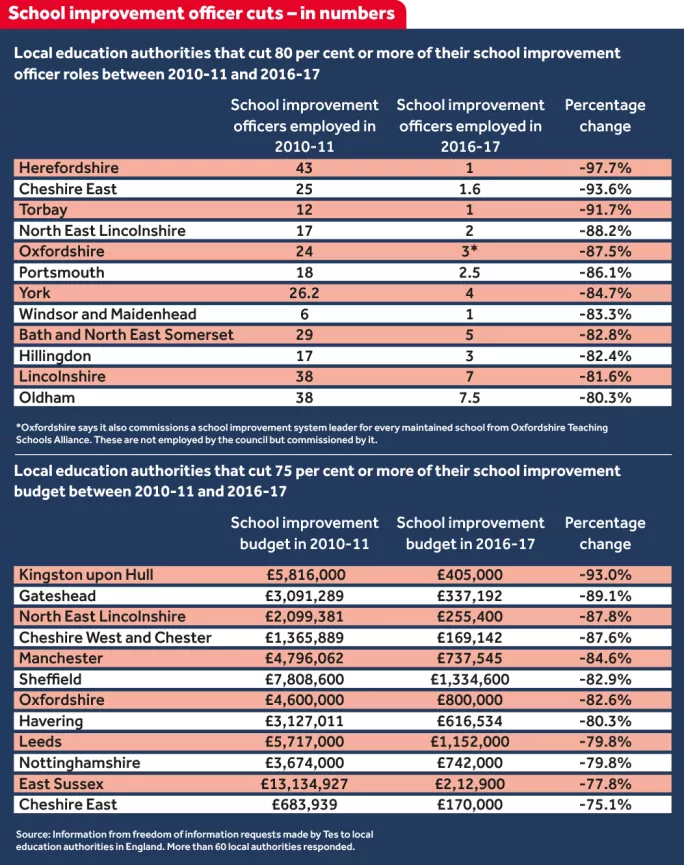

The Tes investigation reveals dramatic drops in the number of school improvement officers employed by many individual authorities.

More than a quarter of the 63 councils that provided figures to Tes have slashed numbers by at least 75 per cent; the majority of councils have cut their numbers by more than half.

In Herefordshire, the authority went from employing 43 officers in 2010-11 to just one in 2016-17. Cheshire East went from 25 to 1.6 in the same time period. They were among 12 authorities where the number of school improvement officers dropped by more than 80 per cent this decade.

School improvement funding has also dropped sharply in certain authorities, with 12 cutting their budgets by more than 75 per cent.

Paul Brennan, a former senior local authority education officer in Leeds and North Yorkshire, warns that the cuts have led to school improvement officers working with unsustainable numbers of schools.

“I spoke to a colleague at another authority who told me that their officers had 40 schools each. This is impossible.”

Mike Parker, the director of the regional network Schools NorthEast, warns that some areas of the country hit by academy problems have been left with a school improvement double whammy. They are faced with both councils and academy trusts without the capacity to make a difference.

“In what other sector would you dismantle a support network without knowing what you were going to replace it with? That is what has happened in education,” he says.

So why has this long-established local authority support for schools fallen away so dramatically? There are two key and interlinked factors - the mass academisation that began in 2010 and severe cuts to local authority budgets.

Local education authorities lose a share of their funding for every maintained school that becomes an academy. And from 2015 they have also been hit by the phasing out of the Education Services Grant, which councils used to provide support services to schools - including school improvement.

So while academy trusts have been supported to grow by the government, town hall budgets have been shrinking.

In 2015, the government reached the height of this ambition by declaring that all schools would become academies. In November 2015 - when full, forced academisation was still on the table - George Osborne, then chancellor, said the government would “make local authorities running schools a thing of the past”. In doing so it would save the £600 million spent on the Education Services Grant.

Holding back the years

The policy of full academisation has since been dropped and local authorities are still responsible for running a large majority of state-funded schools - some 14,000 of them - but without the education services grant.

Crucial funding decisions were made on the assumption that local education authorities were a thing of the past, even though the reality is very different.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says the decision to scrap the education services grant on the basis that all schools were to become academies was “premature and ill-considered.” “Many schools remain under local authority control and the network of multi-academy trusts is not sufficiently evolved to be able to provide support everywhere,” he says.

“We are extremely concerned about the impact on the ability of local authorities to continue to provide services on which many schools rely, including education welfare support and school improvement services.”

A report from the Education Policy Institute thinktank this month warned that there were underperforming groups of both academies and maintained schools.

Jon Ashworth, one of the report’s authors, says the figures revealed by Tes show the need for more money to be spent allowing councils to better support maintained schools.

“I am not arguing that the ESG grant should be returned but councils do need more funding to fulfil their existing school improvement role,” he says.

But many headteachers are not looking for the clock to be turned back five, 10 or 20 years.

Andy Mellor, president of the NAHT heads’ union, says he has seen school-to-school partnerships help to bring in support tailored to meet individual needs.

Mellor, who is on secondment from his job as headteacher of St Nicholas C of E Primary school in Blackpool, sees benefits to a school-led system.

“I think in the past council school improvement teams had been able to ensure schools could get to ‘good’,” he says. “But I think schools working together can go beyond this.

“Before our school became ‘outstanding’, I asked, ‘What does “outstanding” look like in Blackpool?’ We came to the conclusion that to be a truly ‘outstanding’ school, we had to be an outward-facing school that looks to drive school improvement elsewhere. Without a doubt, this approach is what got us to ‘outstanding’.”

There has been limited relief following the scrapping of the £600 million Education Services Grant, with a new £140 million Strategic School Improvement Fund that organisations can apply to. So far, 18 local councils have been successful.

The DfE says it introduced the fund because of its determination to tackle underperformance in all schools.

However, Barton says this not an adequate replacement. “Schools will struggle to buy in other services because their budgets have been cut in real terms,” he says.

“There is a significant risk that schools which most need help will be unable to obtain that support and that pupil outcomes will suffer as a result.”

There are major differences across the country in the number of people still directly employed in school improvement.

In some cases, such as Lancashire and North Yorkshire, councils have been able to retain school improvement staff by selling their services to schools outside their authority.

And Department for Education figures revealed last week following a question submitted by the Liberal Democrats showed that 61 councils - more than a third of education authorities in England - are taking money directly out of school budgets to fund support services such as school improvement.

Sir Kevan Collins, chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation, is not concerned about how schools get their support, but is worried that in some areas what they need is just not available.

“I am not fussy about who provides it but what I think is a concern is that children face a lottery at the moment about whether the right support is there for their school,” he says.

“It has to be the right quality of support and it has to be evidence-driven. The question is, whose responsibility is this?”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters