Attainment gap narrower ‘in more-deprived areas’

The attainment gap between pupils from poor backgrounds and their moreadvantaged peers is narrowest in deprived areas, a Tes Scotland analysis has shown.

And some of the most deprived parts of Scotland are significantly outperforming the most affluent areas when it comes to the attainment of disadvantaged pupils.

The data comes from a benchmarking tool set up by councils that places local authorities into four “family groups”, based on their deprivation levels.

At the more affluent end of the scale is a group containing East Dunbartonshire; East Renfrewshire; Edinburgh; Aberdeen; Perth and Kinross; Aberdeenshire; Orkney; and Shetland.

Highest levels of deprivation

At the other end of the scale are the councils suffering some of the highest levels of deprivation in Scotland: North Lanarkshire; West Dunbartonshire; Glasgow; Inverclyde; North Ayrshire; East Ayrshire; Dundee; and the Western Isles.

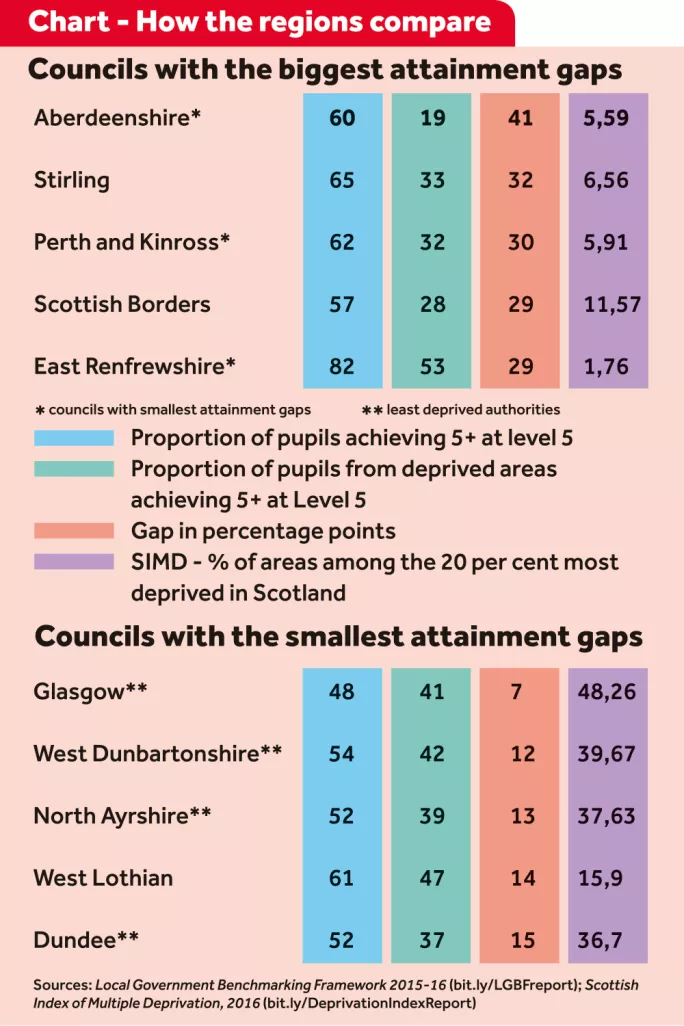

Four out of the five authorities with the lowest attainment gaps at level 5, looking at those who have achieved at least five qualifications, were in the most-deprived areas. Of the five with the biggest attainment gaps, three were in the most-affluent group.

In Aberdeenshire, a relatively affluent local authority, just 19 per cent of disadvantaged pupils achieve at least five qualifications at level 5, equivalent to National 5, making it the worst-performing mainland authority in Scotland on this measure.

However, in North Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire, 42 per cent of pupils from deprived areas achieved at least five qualifications at the equivalent of National 5. The proportions were 41 per cent in Glasgow and Inverclyde and 39 per cent in North Ayrshire.

John McKendrick, an expert in child poverty at Glasgow Caledonian University, said it was reasonable to assume that more affluent authorities - with fewer disadvantaged children - would have more space to support them and raise their attainment. But often, it did not work out that way, he said.

“When there is a squeeze on resources, you have to decide how you are going to direct spending,” said Professor McKendrick.

There was pressure on schools to perform well in league tables, he said, adding: “That naturally leads [some] to push the most able pupils and providing what look like lesser outcomes is not necessarily the most important thing for them.”

‘When there is a squeeze on resources, you have to decide how you are going to direct spending’

The councils did not fit into a neat pattern: disadvantaged pupils in relatively wealthy East Dunbartonshire obtain more qualifications than their peers in any other Scottish council.

In the less affluent areas of Perth and Kinross, just 32 per cent of pupils from deprived areas go on to achieve at least five qualifications at National 5; in Aberdeen, that figure was 33 per cent and in Edinburgh, 38 per cent.

Education secretary John Swinney has identified the lack of consistency in educational outcomes across local authorities as a problem, and has said he wants to group local authorities together in “regional boards” to encourage greater collaboration and cooperation.

He told the education committee last year that it was not good enough that one authority was “a fabulous education authority that adds lots of value to the learning and teaching experience and another authority at the other end of the spectrum doesn’t”.

Larry Flanagan, general secretary of the EIS teachers’ union, said his organisation would like to see more consistency in the way schools in different councils were staffed.

There was too much variation between authorities - in terms of class sizes, pupil:teacher ratios, and support for children with additional support needs or for whom English is a second language - which was putting some children at a disadvantage, he said.

‘Crude’ family groups

Mr Flanagan added: “The poorer the pupil:teacher ratio, the less chance the teacher has to support individual pupils.”

However, some councils denounced the figures produced by the benchmarking tool. Perth and Kinross described the family groups used in the Local Government Benchmarking Framework as “crude”, adding that only 7 per cent of pupils in Perth and Kinross were living in very deprived areas and that, as a result, figures fluctuated significantly from one year to the next.

Vincent Docherty, head of secondary education in Aberdeenshire, claimed the figures did not compare “like with like”.

Historically, Aberdeenshire has always had a high percentage of school-leavers in S4 and S5 going on to college, apprenticeships or work, Mr Docherty said, adding that this was a positive outcome. But because they were leaving school before the end of S6, they had up to two years less to gain qualifications, he explained.

He highlighted that the statistic was based on 52 Aberdeenshire students, which amounted to less than 2 per cent of the cohort.

‘The performance of our pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds remains a key focus’

Scottish Borders Council was critical of the figures because “the information includes the attainment of pupils who left after S4, which can be quite different across Scotland”.

Tracey Logan, chief executive of Scottish Borders Council, said: “Closing the gap in attainment is a key priority for all our schools, but we must recognise that achievement for some of our pupils is about more than just exam results, and that a positive destination on leaving school, whether that is a job, apprenticeship or further education is to be celebrated.”

An East Renfrewshire Council spokesperson said: “The performance of our pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds is the second highest in the country and remains a key focus for us as we constantly strive for improvement.

“Our schools have had additional resources provided to address inequity, including a targeted approach taken to closing the attainment gap, and we are seeing continuous, year on year improvements in this area.”

East Dunbartonshire’s chief education officer, Jacqueline MacDonald said, “As an authority with consistently high levels of attainment, the gap can be higher using some measures; in other measures, the gap is less.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters