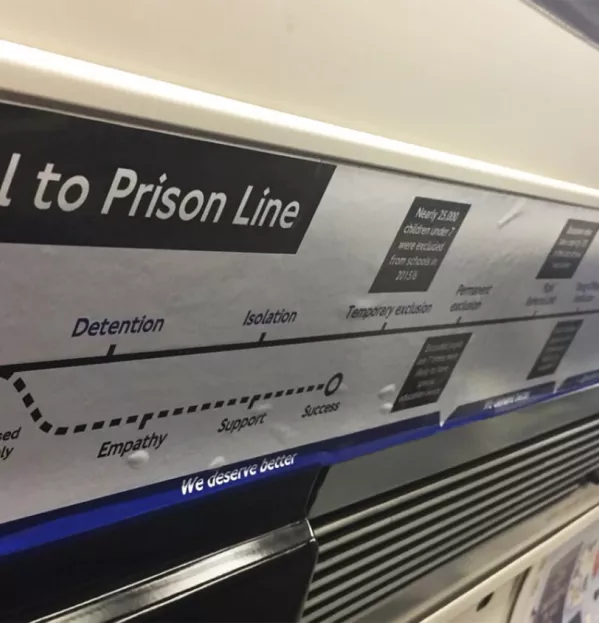

The “from school to prison” posters put up by students in London Tube trains last month powerfully drew attention to excluded children on GCSE results day. Based on the Tube map, they showed a direct line from “sent out of class”, stopping at “permanent exclusion” and with “prison” as the final destination.

The posters were a visual representation of the results of research carried out in Scotland. The Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime tracked almost every child who started S1 in the capital in August 1998 - around 4,300. By 2013, the cohort was aged 25 and one of the study’s main findings was that if a child was excluded by the age of 12, he or she was four times more likely to be in prison by age 22. This makes exclusion from school one of the best predictors of later criminal behaviour.

As a result of research such as this, for a long time the focus north of the border has been on driving down exclusions, with values-based approaches replacing the punitive sanctions of old. So if you look at the current approaches used in Scottish schools to manage behaviour, then exclusion, punishment exercises and detention are still there, but more common are the promotion of positive behaviour, rewards systems for pupils and buddying and peer mentoring.

One authority that is taking this a step further is Clackmannanshire, which is introducing a “trauma-informed” approach into its schools called Readiness for Learning (R4L). The council says it is unique in Scotland.

The aim of R4L is to train school staff to help pupils to understand and manage their emotions from an early age. It combines bespoke interventions for individuals with universal approaches that the council hopes will make school a welcoming space for all. Some schools are turning off strip lighting, muting bright colours in classrooms and playing music between classes.

In Lornshill Academy, a depute head talks about the impact the approach has had on temporary exclusions: there were only two exclusions in 2017-18, compared with several dozen the year before. In Scotland as a whole, permanent exclusions have been all but wiped out. The latest figures from 2016-17 show that just one pupil was “removed from the register” - that was down from 60 pupils in 2010 and 248 a decade earlier in 2006-07. The number of temporary exclusions has also plummeted, with 26.8 exclusions per 1,000 pupils in 2016-17, compared with 63.5 per 1,000 pupils in 2006-07.

The approaches of England and Scotland on this issue could not be more different. While south of the border Amanda Spielman, head of Ofsted, the schools’ inspectorate, has announced a crackdown on poor pupil behaviour, here, Graeme Logan, acting chief inspector of education until November 2017 and now a top civil servant in the Scottish government’s learning directorate, told new teachers recently that if pupils were being disruptive, they needed to ask themselves: is your lesson worth behaving for?

Some will baulk at this. Indeed, Scottish teachers were quick to respond, saying that good behaviour must be the norm in every lesson. Others will take issue with the Clackmannanshire educational psychologist who signs up to the view that “all behaviour is communication”, and they will object to a seven-year-old who had been “violently kicking walls and teachers alike” simply being escorted back to class by the headteacher.

However, we know more now about the impact that living in an aggressive and unpredictable environment has on children and their ability to learn. To do nothing in school to mitigate those effects would be wrong. Pupils need to feel safe, supported, valued and listened to. But let’s not forget that staff need to feel that way, too.

@Emma_Seith