Inspectors to scrutinise the transfer of powers

School inspections are to be used by the Scottish government to monitor whether councils are devolving enough power and money to heads, as it attempts to step up its reform agenda despite shelving the long-awaited Education Bill last week.

The government will also use feedback from headteachers and council self-evaluations to monitor progress, and councils failing to deliver will receive “support and challenge” from inspectors, as well as local authorities’ body Cosla and the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland. Failure to make progress will also lead to “escalation to audit and scrutiny inspection bodies”.

Education Scotland will be expected to publish three reviews in the coming academic year looking at: readiness for empowerment (to be published in December); curriculum leadership (March 2019); and parent and pupil participation (June 2019).

A spokeswoman says: “The findings from these thematic inspections will be used to identify what is working well and aspects that need to improve. As part of the inspections, HM Inspectors will visit a sample of schools and have discussions with a range of stakeholders.”

Detailed planning for these national inspections is underway and further details will be published next month.

The plans emerged in the deal that the Scottish government and Cosla have agreed in lieu of a new law that would have guaranteed headteachers more control over staffing and what is taught in their schools.

Just last year, first minister Nicola Sturgeon said that the new Education Bill would “deliver the biggest and most radical change to how our schools are run”.

However, education secretary John Swinney announced last week that he was putting the legislation on hold in a bid to give councils the chance to hand more power to schools voluntarily. He said that progress over the next 12 months had to be “sustained and swift” or he would “return to the Parliament and introduce an Education Bill”. And it is Education Scotland that has been largely charged with monitoring progress.

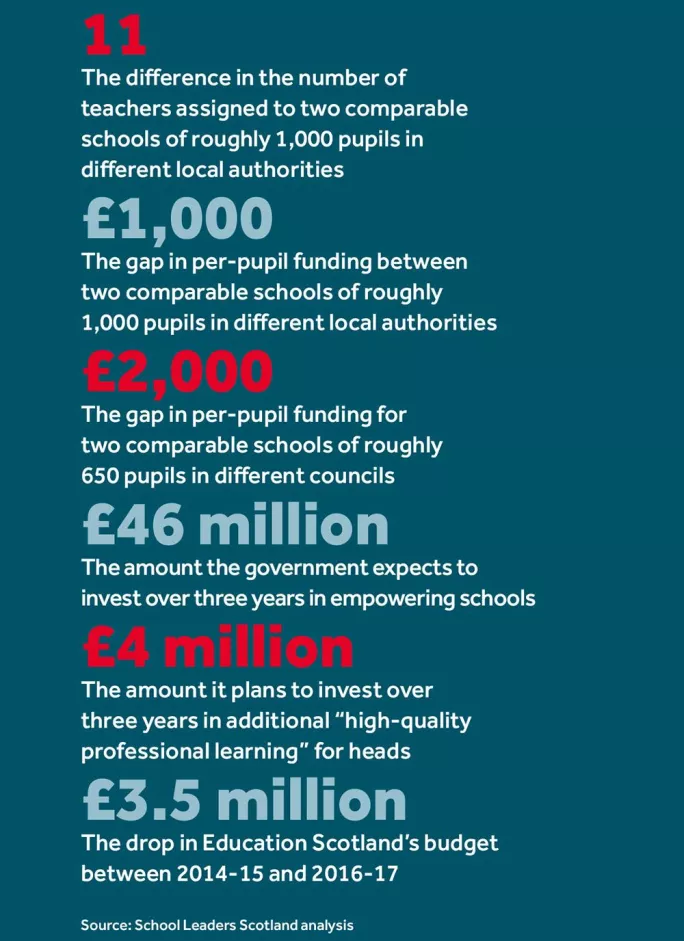

Secondary headteachers, however, have questioned whether the schools’ inspectorate has the capacity to keep tabs on Scotland’s 32 local authorities. New analysis shows that the Education Scotland budget has fallen by £3.5 million in just two years, from £39.062 million in 2014-15 to £35.552 million in 2016-17.

School Leaders Scotland (SLS), which represents secondary heads, also says legislation would have addressed two of its key concerns: the disparity in staffing and funding between similar schools in different local authorities.

According to SLS, per-pupil funding can vary by as much as £2,000 and staffing by over 10 full-time equivalent teachers, depending on the authority a school is in.

SLS general secretary Jim Thewliss says: “Devolved school management does not tackle inequality and inequity, it perpetuates it. We need a national funding formula and a national minimum staffing standard.”

SLS also says that, while it is disappointed the government has pulled back from legislating, it will “continue to seek to engage”.

Generally, there is support for Swinney’s move away from legislation and towards collaboration. The analysis of the 870 consultation responses to the proposed bill found that there was “support for the principles behind the Education (Scotland) Bill” but “less support for legislation to enshrine these principles”.

In the wake of Swinney’s announcement, the EIS teaching union welcomed the decision to “pause” the legislation. It said it supported the partnership approach agreed between national and local government, although it said “such an approach must be extended beyond politicians to include the profession itself”.

Scottish education expert Keir Bloomer, however, questions whether Swinney’s new approach - described as “the mother of all ministerial climbdowns” by Labour’s Iain Gray - will deliver change more quickly.

Last week, Swinney told Parliament that he now hoped to deliver more power for heads “faster and with less disruption in partnership with local authorities”, arguing that Scotland would have had to wait for 18 months for the Education Bill to come into force.

But Bloomer, convener of the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s education committee, says that “legislation would have ensured something significant happened everywhere”.

“[Swinney] is not right in saying it will be quicker,” he adds. “It won’t be. You may get action in some places faster than you might otherwise have done, but you won’t shift the whole system faster.”

There is also “a big professional development issue” that needs to be addressed when it comes to school leaders, says Bloomer.

“Simply telling people they have the right to take additional decisions is not necessarily going to lead to them exercising these powers either readily or effectively,” he argues.

David Cameron echoes this point. The former education director carried out a review of devolved school management in 2010 that - had its recommendations been implemented - would have achieved much of what Swinney is trying to achieve today.

Cameron believes that “creating a more flexible and responsive system is likely to lead to better outcomes for children”. But, he says, “the blunt reality is when you give powers to headteachers, you give them to [both] the good ones and the ones who are struggling.”

Mr Swinney announced £46 million of investment to support the reforms over three years.

The bulk - £32 million from the Scottish Attainment Challenge - has been earmarked to improve the attainment of looked-after children, with £4 million for additional “high-quality professional learning” for heads. The remainder has been set aside to support the work of regional improvement collaboratives.

However, the one thing heads have consistently called for if they are to be responsible for bigger budgets is more business management support. The government says there is “no new spending commitment” on this just now - although the financial memorandum for the bill estimates that could cost anything from £5 million to £20 million a year.

The government also says it has ruled out a fixed national funding formula for schools, but in the future more funding will be delegated to schools consistently across Scotland.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters