The schemes giving young offenders another chance

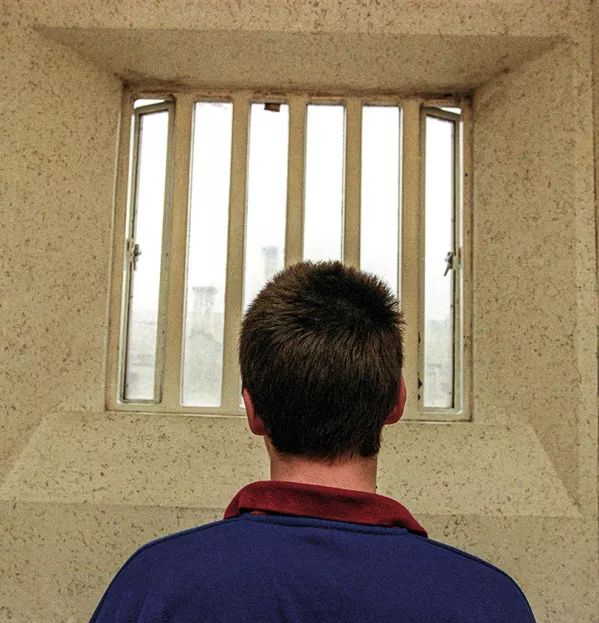

Luke* is at his youth justice hearing, waiting to find out if he will get a custodial sentence. He’s 16 and wearing an ill-fitting suit borrowed from a friend. He has a black eye and is hungover. For a long time, Luke’s behaviour has erred on the wrong side of the law and, a few months ago, an incident led to his being arrested for assault.

Luke’s future depends on today’s judgment. He faces being sentenced and sent to a young offenders’ institution which, statistically speaking (see box, below), means there is a 38.5 per cent chance of his reoffending within 12 months of release. It’s a path many struggle to get off.

But instead of getting a custodial sentence, Luke is sent on a two-week bespoke course to put him on a different path: one on which he stands a good chance of going on to have a successful, healthy, law-abiding life.

Luke will take his first steps on this new path at West Lothian College in Scotland, where a new scheme means that young people facing criminal charges can be enrolled in college instead of being sent to prison.

Principal Jackie Galbraith admits that running the programme for the past six months has been a challenging - and expensive - process, but she believes it could have a very positive impact. “Our job is to inspire and help all young people to succeed, and if we can help those who are facing the most challenges in their life to come on to a positive path, it means success for them and for their families,” she says.

The programme, which has been developed in partnership with a local lawyer, mainly supports young men, as this is the demographic more at risk of offending, Galbraith says. “We want to avoid them becoming trapped in a life of crime or the worse possible thing, which would be them dying by suicide. We see a lot of that in West Lothian among young men.”

‘It’s not black and white’

So, how exactly does the initiative work? And is it something other colleges could look to introduce?

Through the strong relationships that the college has built with local organisations, Galbraith and her team are alerted when a young person enters the custody system and their case is due to be heard. A meeting is held with a member of pastoral staff from the college, a social worker and the young person, and they discuss the situation, and any interests and challenges the young person may have. If the youth justice panel agrees, a bespoke two-week programme is created, including mental health and wellbeing support, skills building and careers advice.

Two weeks is, undeniably, a very short amount of time for any college course - and questions may be raised about how much impact it could have. But Galbraith says the course is purposefully short to ensure it is attainable. “It’s important for the young people to see they’ve achieved something. It’s not a two-week course and that’s it; we do follow through. It’s enough time to build a relationship with them and we encourage them to engage in more formal qualifications afterwards,” she says.

“It’s not black and white; every young person is different. But what we see in the college is, if you can win their trust and support them through a few false starts, and encourage them back again, then, absolutely, it can be a really positive experience.”

While this bespoke approach can be beneficial, Galbraith admits the time and resources required to make it work mean it may not be easy for other providers to replicate. So, what are the other options for supporting young people at risk of offending?

Across the UK, there are small pockets of provision with the same goal: to change the course of these young people’s lives. Bounce Back, a charity and social enterprise focused on training and employment for ex-offenders, is rolling out a programme to re-engage this cohort of young people with education and give them hope for the future.

The charity is in the process of establishing digital hubs across London to support young people either at risk of, or already engaging in, offending behaviour, helping them to get work experience, qualifications and, ultimately, employment in the digital sector.

The digital sector was chosen because of the expanding opportunities available but, first and foremost, says Bounce Back’s chief executive, Julian Stanley, the hubs are about getting learners re-engaged in education, skills and employment - and there is no quick fix for that. “These young people often do have ambitions but they’re not ready to take those steps; they don’t know how they actually deal with the disciplines and the behaviours to get from A to B,” he explains. “It’s a long journey and the focus should be on ensuring changes are happening because the young person wants them, too, rather than saying, ‘Here’s a programme: go through this, and then you’ll get this’.

“There’s something in the process of uncovering what they can do to change for themselves that’s really powerful. Intervention must be welcoming, appropriate and challenging, to a degree.

“People often are motivated by wanting to earn money or change their lives but the journey of making those small changes to be ready for work experience and employment is quite significant.”

No matter how beneficial the journey might be for young people, though, there is no getting away from the fact that this kind of provision is niche and takes investment over a long period of time.

However, Gill Robinson, who has worked in youth justice for decades, most recently as chair of the Youth Justice Improvement Board’s Improving Life Chances Implementation Group in Scotland, says there are simple - but not easy - ways that providers can begin to make a difference straightaway.

Crucially, she says, in order to support this group of students, teachers must be aware of the factors that led to offending behaviour.

For example, she says, being excluded from school is often the turning point: young people find themselves cut off from a number of positive connections, whether it be a teacher they really trust or a football team they love being a part of. Typically, she adds, these young people don’t have stable home lives and will have experienced “multiple traumatic events”. Therefore, once education is taken away, there often isn’t any infrastructure in place to prevent offending.

If a young person does return to college, whether it’s justice system-mandated or voluntarily, staff must invest time in building a relationship and establishing trust, she says.

“It’s crucial that staff get to know the young people they are working with and prioritise relationships with them. They are now in the situation where they will be one of the relatively small number of individuals in those young people’s lives who are able to provide a pro-social model,” she says. “There will be suspicion, there’s no doubt about that. Students will potentially have some quite negative experiences of their schooling, which may have set up some real anxiety in them. They will carry a lot of soreness and staff must take the time to build up trust.”

Students must be offered a real chance to engage in education for education’s sake - and staff must foster the promotion of hope, she says.

Robinson believes the arts are a great way to engage young people in positive activity, as is work around social injustice.

She recalls a programme of work she ran with some young people in custody on the Holocaust, and how passionate they became about the topic. “It was really moving to see that they were engaging with the issues at an emotional level, and how much that helped the whole view of self. They hadn’t realised they were reading difficult texts because they were completely focused. An engaging project like that is very worthwhile,” she says.

“These young people’s views of their own futures will be very, very limited. This can be an impact of multiple care placements or multiple bereavements; they keep losing the people who are closest to them in their lives. When that happens, it’s very difficult not to see yourself as somebody who is going to be lost. Promotion of hope for the future is absolutely key.”

Ultimately, though, it is clear that supporting this group of young people takes money and time; two things which are in short supply for many FE providers.

But if colleges can get that support right, then the impact is nothing short of transformational, says Robinson: “If you can get to the point of them having an apprenticeship or a job, then we know the likelihood of their offending once they’re in that place reduces dramatically.”

Galbraith agrees. “We are like every other college; we don’t have enough funding. But we’ve decided, as a college, that this is a key priority for us and we will resource it with whatever limited funding we have,” she says.

It’s impossible to predict where students like Luke will end up, what jobs they’ll go on to have or how happy their lives will be. But faced with two life-changing paths - one that sees them enter the prison system and potentially go on to reoffend, versus another, which gives the opportunity to re-engage with education, to build positive relationships with adults and to begin to hold hope for the future - it’s obvious which one is better for them to walk down.

Kate Parker is an FE reporter at Tes

*Luke is not a real person

This article originally appeared in the 30 April 2021 issue under the headline “Young offenders get chance to swap custody for college”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters