Teacher, tailor, YouTuber, spy

Kerri Sellens looked at the piece of paper and considered what the appropriate reaction to the picture in front of her should be. She had asked the children to draw the job they wanted to do when they grew up and one child had drawn something…unexpected.

“[He had drawn] a ‘fidget-spinner shop owner’,” she recalls. “He was so sincere. It really was his dream to own a shop full of fidget spinners.”

After a pause, she adds: “Thinking about it, I haven’t seen a shop dedicated to them, so maybe he is onto something…”

The aspiring fidget-spinner entrepreneur was one of thousands of pupils who answered their teacher’s request to take part in Drawing the Future, a study into children’s career aspirations conducted by the charity Education and Employers, in collaboration with Tes, the NAHT headteachers’ union and the UCL Institute of Education, with the support of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Alongside the perhaps predictable professions of “sportsperson”, “teacher” and “doctor”, unexpected aspirations were not limited to the one above. Other choices included DJ, YouTuber and - from a child in an area of the country that has been affected by terrorism - “bomb defuser”. They explained on the picture that “people are praying to God to stop terror attacks and if I can prevent bomb[s] I would stop people from losing their lives”.

There are certainly social influences at play in such choices, as well as myriad others, but how do the selections reflect on the careers education they had received, if indeed they had received any?

Historically, careers education is not something that UK schools have done well. In 2016, a report by Ofsted found that 36 out of 40 secondary schools visited by inspectors had not demonstrated an effective approach to enterprise education in the curriculum, while more recent research by the charity Teach First found that less than a third (32 per cent) of the most disadvantaged students considered their careers advisors to be helpful.

The scale of the problem has not gone unnoticed by politicians. Last month, skills minister Anne Milton launched the government’s new careers strategy, which aims to have a dedicated careers leader in place in every secondary school by the start of the next school year. She also pledged to direct £2 million towards trials of careers activities in primary schools.

That something happens earlier than the secondary phase is key, according to the Drawing The Future study, says Elnaz Kashef, head of research for Education and Employers.

“Our previous research has shown that kids start thinking about who they want to become from an early age,” she explains. “But they have a narrow view of the world of work and their aspirations are limited to who they meet. They also rule out career pathways from an early age, reflecting their gender-stereotypical view of specific jobs and low self-efficacy.”

Future proofing

The Drawing the Future study built on this research by asking pupils to draw what they wanted to be when they grew up and to say whether they knew anyone who did that job (some of the resulting artwork and responses are reprinted on these pages), while data on the pupils and the schools was also collected - for example, the percentage of students eligible for free school meals (FSM).

Between September and December 2017, more than 13,000 UK pupils between the ages of 7 and 11 took part in the study. Schools were recruited to participate on a voluntary basis. Data was gathered by class teachers and sent back to Kashef’s team to be analysed according to factors such as pupils’ gender and economic background.

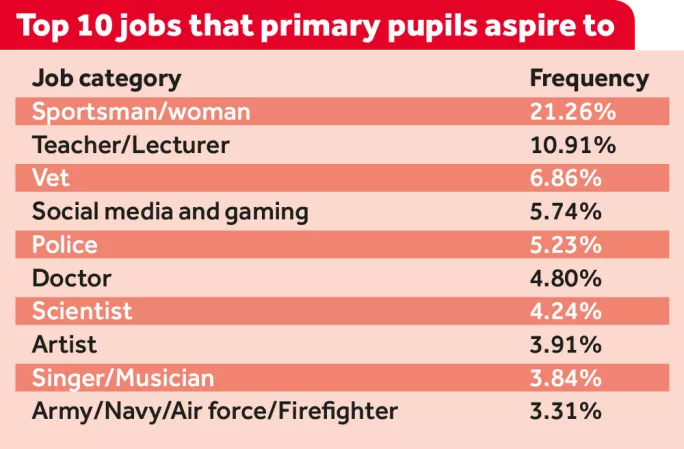

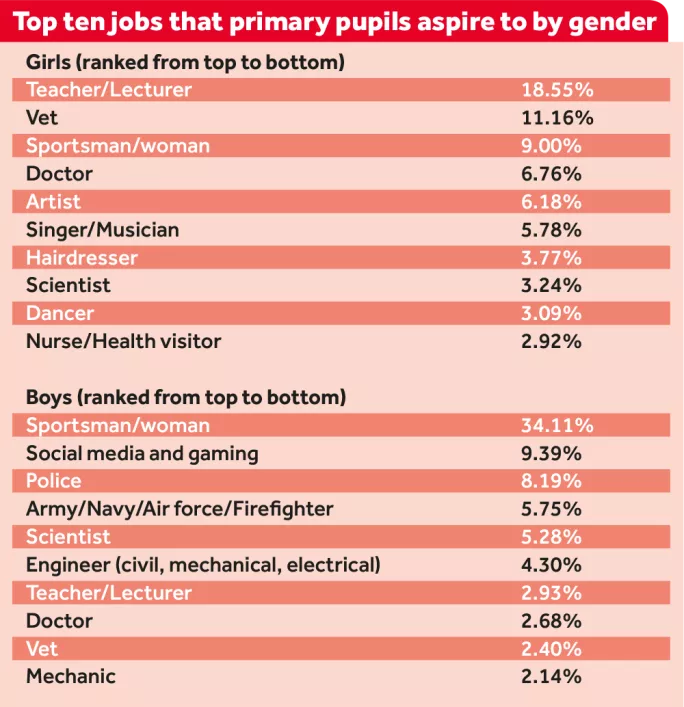

In the UK, the top job that children aspired to was “sportsman/woman”, with just more than one fifth (21 per cent) of all pupils opting for jobs in this category.

Sue Wilkinson, chief executive officer of the Association for Physical Education, was understandably “delighted” by this news.

“Traditionally, young people who come from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas used sport as a means to ‘escape’,” she says. “We think that this is an even greater influence today when you consider that sport is currently one of the top 10 industries in the world and in the UK it is worth £23 billion and employs more than 1 million people - it is no longer seen as a second-class industry.”

And despite recent data from university admissions service Ucas suggesting that the number of applicants for teacher training fell by a third between 2016 and 2017, “teacher” was the second-most popular job among primary children, chosen by 11 per cent.

The rest of the top 10 consists of similarly “traditional” roles, which may run counter to what some may have expected. As Paul Clayton, director of the National Association for the Teaching of English (NATE) points out, the data appears to “undermine that commonly held belief that children are unrealistic about their aspirations, simply wanting to become famous and wealthy”.

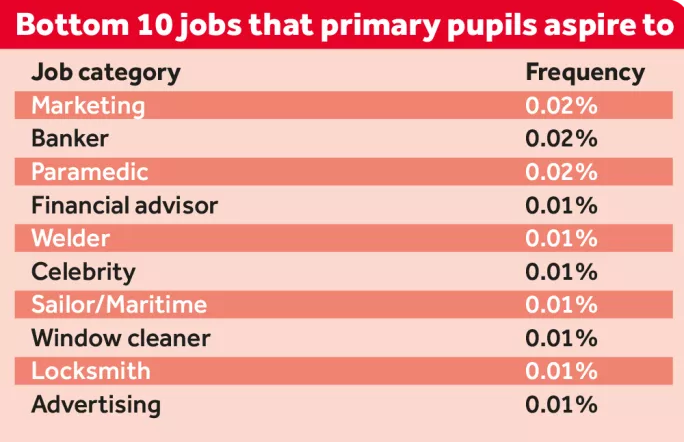

The top spots are largely dominated by what Clayton calls “everyday role models” such as teachers and police officers. Meanwhile, becoming a “celebrity”, was an aspiration chosen by just 0.01 per cent of pupils.

This is something writer and campaigner Natasha Devon also welcomes.

“There is still a view in some quarters that ‘all young people just want to be famous without doing any work’ - it’s an attitude that I encounter often - and this survey thoroughly debunks it,” Devon says.

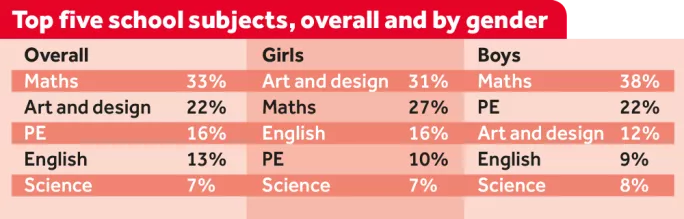

The messages are not all positive, though. Pupils’ career choices are not consistent with the subjects they named as their favourites. While “sportsman/woman” was the top job, the top subject was maths, chosen by a third (33 per cent) of pupils, followed by art and design, chosen by more than one fifth (22 per cent) of pupils. PE, meanwhile, was third on the list, chosen by 16 per cent of pupils.

This suggests that children may not see a clear connection between what they study in lessons and the careers that will be open to them in future.

The research also confirmed what the charity had feared: aspirations were being limited by socioeconomic status and lack of exposure to a variety of careers.

Diving below the headline figures, there is some evidence that children in deprived schools aspire to professions in lower-earning sectors. So those in more-deprived areas were more likely to pick mechanic, whereas those in less-deprived areas would pick engineer; the same went for sales assistant and manager, and police and lawyer.

“There is also some evidence that certain creative professions with very high barriers to entry are more popular to boys in less-deprived schools, such as being a singer/musician, actor/actress and author,” says Kashef. “Among girls, architects, engineers and vets are more popular in less deprived schools, whereas hairdresser, nurse, retail sales assistant and beauty therapist are more popular in the more deprived schools.”

Limited aspirations

For Lee Elliot Major, chief executive of the Sutton Trust, this is a big concern.

“Our research has shown just how much aspirations matter in shaping young people’s outcomes after school, so it is worrying that poorer young people are more limited in the jobs they aspire to,” he explains. “They may not see career paths like medicine and law as a reality for them, even if they have the potential to get there.”

But according to the data, economic background is not the only factor that could limit children’s aspirations. When you split the results by gender, it becomes clear that stereotyping is still entrenched, even at a young age. Hairdresser, nurse, dancer and fashion designer all feature highly in girls’ career choices, while boys favour jobs such as mechanic, engineer, airline pilot and roles in the armed forces.

This gender split is particularly troubling to Mumsnet founder and chief executive Justine Roberts. “Gender stereotyping is pernicious and parents have to fight against it on many fronts,” she says. “Overcoming barriers to women’s full participation in all fields of work won’t just be good for women and the men they live and work alongside; it will be good for children, too.”

For Devon, the stereotyping of boys’ roles is equally a matter for concern, particularly considering that while “teacher” is the top job for girls, it falls to seventh on the boys’ list.

“In light of the relative dearth of male teachers and therefore male role models for children, I’m troubled that far more girls want to go into teaching than boys,” Devon says. “It’s important for children’s role models to be diverse.”

So if children’s career aspirations really are being limited by poverty and by exposure to careers, what can we do about it?

“This research holds messages for schools about the importance of getting kids to meet a wide range of volunteers from the world of work in order to tackle gender stereotyping from an early age and to broaden their horizons,” says Nick Chambers, chief executive of Education and Employers.

Career visibility

The main issue, he believes, is career visibility. If this is the case, then the problem should, in theory, be relatively easy to fix. Chambers thinks schools could make a real difference by organising visits from a greater variety of people working in different sectors, something that his charity Primary Futures facilitates, giving primary schools access to 40,000 volunteers in diverse careers.

“Kids don’t know what they don’t know. So, we would like to invite employers to connect with their local schools and help the next generation of Britain’s talent be better informed about the opportunities ahead of them. We know from evidence that this has a large impact on their journey to adulthood,” he says.

Michelle Doyle-Wildman, acting CEO of parents’ organisation PTA UK, suggests that reaching out to parents could be an easy way to access a selection of candidates for visits.

“We know from other research that children cite their parents as their top role models. So schools should seek to actively engage parents and carers to share their experiences and talk about their jobs in the classroom,” she advises.

However, Gill Collinson, of the National Stem Learning Network, has some words of caution about oversimplifying the problem. She stresses that there are multiple factors that influence a young person’s view of their preferred job, so we mustn’t fall into the trap of seeing visibility as the “silver bullet”.

“Teachers, parents and others need to adopt a ‘multi-pronged’ approach to shifting the career decisions of young people,” she explains. “We need to be aware that students’ choices are complex.”

Wilkinson agrees that improving visibility alone will not fix careers education. “Lots of my classmates wanted to be firemen and policemen, teachers or airhostesses when I was in primary school because they came into school and gave talks. But none of my friends went on to join these professions,” she remembers.

A holistic approach would be welcomed by Chambers, but he insists that careers education at primary should be part of the plan. He believes the research his team has conducted with the Drawing the Future survey proves many children have limited views on careers at an early age and that we have a duty to level the playing field.

“If the UK is serious about improving social mobility, we need to ensure that we start from primary,” he says.

Start earlier and children may still wish to be one of the top 10 options, of course, but at least you plant a seed that there is more out there in the world of work than they imagine. That might stir a new passion for a certain subject and provide a foundation for future aspirations and choices. And it might mean the child with visions of a fidget-spinner empire expands their remit to supplying the whole gamut of classroom fads.

Helen Amass is deputy features editor for Tes and a former teacher. She tweets @Helen_Amass

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters