Whatever happened to parent-led free schools?

“It has been phenomenally exciting, and phenomenally exhausting. And, at the end of it, to see our first set of students getting their GCSE results was wonderful.”

What started as a conversation among friends in a back garden about school places in their neighbourhood sparked an ambition to open a new school.

Three years of hard work later, their idea became a reality and last summer, the first children to join their free school were celebrating “fabulous” GCSE results.

Kerstyn Comley and the group who founded Wapping High School, in Tower Hamlets, East London, were the among the first parents to realise a vision for a new generation of state schools. Parent-led free schools were at the heart of the incoming government’s plan for a “Big Society” that would empower communities by transferring power from politicians to the people.

Parents, teachers and community groups were invited to bid to start new schools from scratch. The policy, inspired by Sweden’s free schools’ movement, launched with a series of high-profile new schools supposedly bringing the Big Society to life.

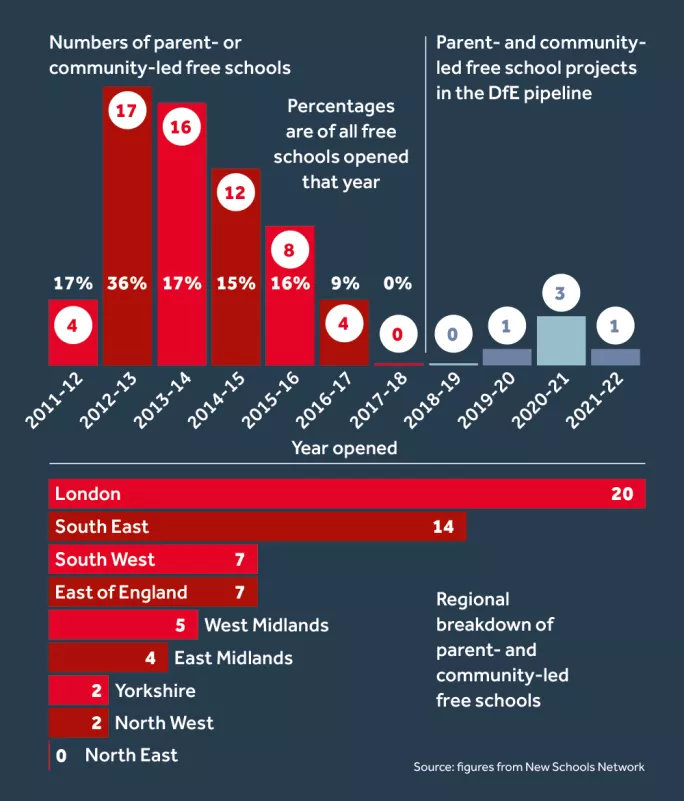

Now, less than a decade on, the idea of a parent-led school revolution is already largely forgotten. Figures provided to Tes by the New Schools Network (NSN), the charity set up specifically to help new groups open such schools, show that the number of parent- and community-led free school openings has been in steady and continual decline since 2012-13.

Although 61 are up and running in England, only four parent- or community-led schools opened in 2016-17 and none at all have been set up in this academic year.

The figures also show that while parent-led free schools may have got national attention, they were far from being a national phenomenon. In London 20 opened and in the South East another 14 more, but across the North of England there were just four, with none at all in the North East.

Most free schools open today are run by existing multi-academy trusts or schools. The Department for Education has said that it welcomes anyone applying to set up free schools, including parent groups.

However, there now seems to be consensus across the education sector that the free school programme as it exists today is far removed from what Michael Gove and David Cameron were championing en route to power in 2010.

High-profile supporters and critics of free schools claim the government has changed its attitude towards the policy, making parent-led schools less likely.

Toby Young, the journalist and author, has been at the forefront of the movement since it began. He led the creation of the West London Free School in Hammersmith, which was the first in the country to secure a funding agreement. He has been a high-profile champion of the original policy and more recently was director of the NSN, until he stepped down in March.

“I think the Department for Education has become progressively more risk-averse since the policy was introduced in 2010, and that has meant fewer parent-led schools,” he says.

According to Young, the DfE’s attitude is now “better the devil you know”, which has meant “plain vanilla free schools set up by large academy chains”. “That’s short-sighted because it’s only by allowing some innovation that we’ll find out what works best,” he says.

Young warned back in 2011 that making the free school application process more demanding would make it harder for individual groups to open new schools.

But, for some, that might be seen as a good thing. The free school policy was launched at pace and with a very high profile - which inevitably meant that it had a series of high-profile failures. Some of the first free schools to open in the country were also some of the first to close.

The parent-led Discovery New School, in Crawley, West Sussex, which opened in the first two years of the programme, was closed by the government after it failed an Ofsted inspection. Durham Free School, also parent-led, went the same way and Bradford’s Kings Science Academy - personally endorsed by Cameron himself - became engulfed in a fraud scandal that led its founding principal being jailed. Although Kings was not a parent-led school, such scandals have led to the DfE tightening up the applications processes.

Comley, chair of governors at Wapping High, says these changes to the application process meant that her group had to submit a 250-page document rather than the 20-page one that would have been required, had they entered during the first wave of free schools.

She tells Tes that the biggest challenges for the parents to overcome were finding a site and ensuring that the group had the right education expertise.

“We were determined and we worked very hard but we were lucky. We were in contact with really fantastic education consultants who supported us. We had access to this, being in London. If you don’t have this access, I imagine it would be very hard for a group [of parents] to put together a convincing document,” Comley says.

She adds that it is difficult to advise parents on how to pursue a free school application now because the landscape has changed.

“The original vision for free schools has not really panned out,” she says. “It has not been about introducing new people into education. I think, sadly, the government has missed an opportunity to support different groups into the education system.”

Critics of the free school policy also agree that the DfE has moved away from its original vision for free schools.

The department’s own guidance says that “free school” is its term for any new academy. Any local authority that wants to open a new school must first seek to establish a free school and find a suitable sponsor.

Mary Bousted, joint general secretary of the new NEU teaching union, says it is only this intervention that stopped the free school programme from “withering on the vine”.

“In reality, there have been just a handful of genuinely ‘parent-led’ free schools, since most parents are perfectly happy with their local school,” she says.

Bousted suggests that high-profile free school failures led to the government turning to established MATs to open new schools instead. However, she insists that MATs are not a solution to the problems faced by some early free schools, highlighting the recent case of Wakefield City Academies Trust, which has had to ditch all 21 of its schools amid questions over its finances.

Two years ago, when Lucy Powell was shadow education secretary, Labour produced research suggesting that parent-led free schools were making way for new schools run by MATs.

The analysis found that of the first wave of free schools approved, 35 per cent (14 out of 40) were parent-led. But by the time approvals reached waves nine and 10 in 2016, this figure had dropped to just 5 per cent.

Powell says the first waves of free schools were centred around London and set up according to the vision of the original movement by people who had campaigned for the policy. However, she claims that this policy is now effectively dead and independent groups are unlikely to get a look in unless they are partnered with a strong sponsor.

It is meant as a criticism, but could this be the future of parent involvement in the system? Could free schools effectively partner up parent campaigns with trusts that the government has faith in?

Mark Lehain, interim director of the NSN, thinks so. He says that while parents might no longer be involved in the “nitty-gritty of writing bids”, they can still have a voice in helping to set up these schools.

Lehain, who is also director of the Parents and Teachers for Excellence campaign group, says: “We know that in a number of cases, it’s a group of parents who start the campaign for a great new school, and play a huge role in founding the school, even if it’s not officially a parent-led group.”

The NSN has a list of nine parent- or community-led free school projects that it has supported but have not yet resulted in new schools. Of these, five are on the DfE’s list for free schools in the pipeline; another two are parent-led projects that have fallen through.

For some, the decline of new parent-led schools is about the government abandoning the boldness of the original vision. For others, it’s a tacit admission that asking parents to set up their own schools was an always an impractical idea.

Lecturer Dr Rob Higham, who researches free schools at UCL Institute of Education, argues that we are seeing the decline and fall of David Cameron’s Big Society agenda and the rise of MATs.

“This combination has meant both less prioritisation of free schools as part of an alleged process of civil society empowerment and more willingness to encourage and accept existing sponsors to open multiple free schools,” he says.

This academic view is echoed by consultant Helen Stevenson, who has overseen several free school bids for multi-academy trusts. She suggests that it is the popularity of the free school programme among MATs that may have actually surprised the DfE and has changed the landscape.

“If there is limited resource available for each wave, the volume of bids for new schools from MATs, who can evidence a track record of performance, perhaps makes it less likely individual groups will be successful,” she says. Put simply, one government education reform has overtaken another.

The DfE insists that it is “especially interested in new free schools that will bring innovation”. It is set to invite a new wave of applications shortly, “focused on allowing challenging areas to feel the full benefit of the programme””.

Whether the next generation of free schools will bring innovation or take the programme into new areas remains to be seen. But whatever happens next, it looks like new parent-led schools are already a thing of the past.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters