- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Why creativity is just knowledge - and what that means for schools

Why creativity is just knowledge - and what that means for schools

In 2015, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development launched Future of Education and Skills 2030 - a project that, among other things, argues that education must focus on helping students develop the skill of creativity to ensure they are well prepared for an uncertain future.

Just a few months into the project, the OECD released an invitation to tender, entitled Teaching, assessing and learning creative and critical thinking skills in primary and secondary education, in which they freely admitted “…it is not clear how creativity can be visibly and tangibly articulated by teachers or students”.

It’s a shame that the very people demanding that education focuses on creativity have little idea what this cognitive process is or how it can be cultivated.

So, what do teachers need to know about creativity in order to help their students develop it?

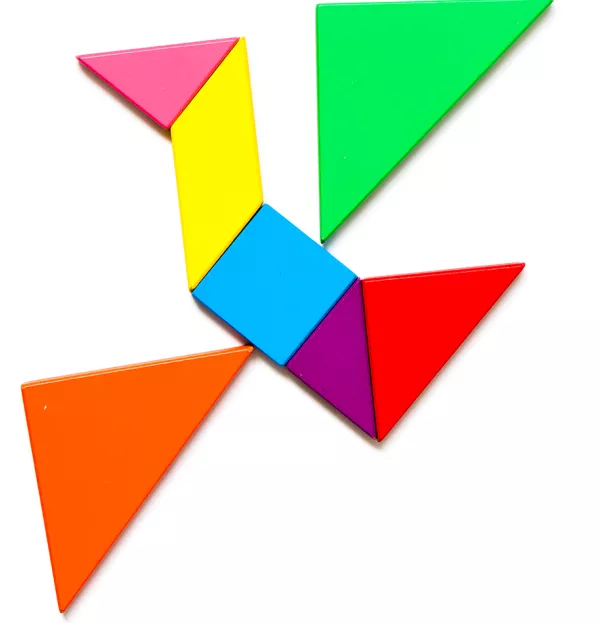

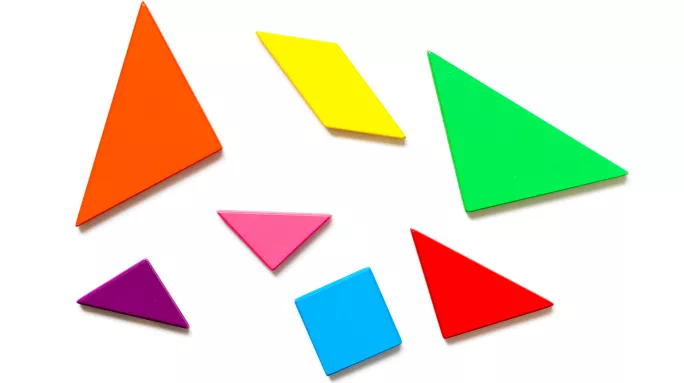

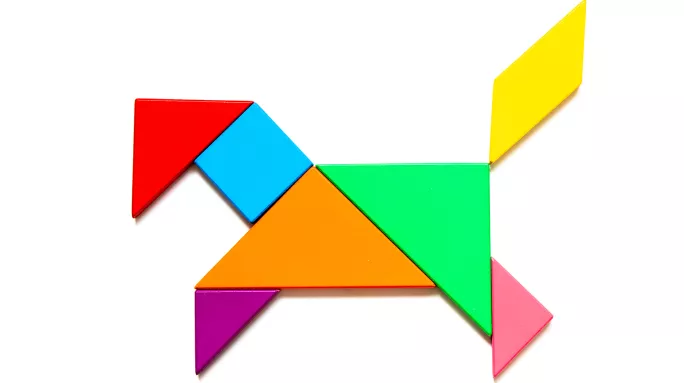

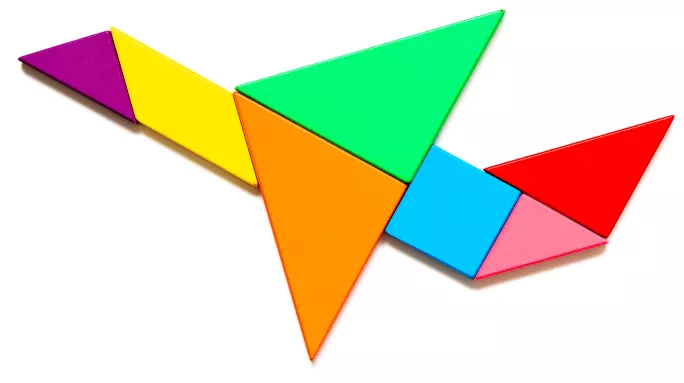

The best way to understand creativity is to think of Tangrams: a puzzle whereby players must rearrange a handful of different shapes to create a specific but undetailed figure.

Building from this, imagine that all the memories in your brain are different shapes. Each fact, each concept, each experience is represented as a unique mental structure in your available mental inventory.

Now, imagine a particular problem you are attempting to solve as an undetailed figure. This problem could be externally motivated, as is often the case in science subjects (for example: “How do I clear plastics from the ocean?”), or it could be internally motivated, as is often the case in arts subjects (for example: “How do I express my angst using colours on a canvas?”).

What we call creativity is simply the re-arranging and re-configuring of your current mental structures in order to build a new mental structure that matches and addresses a relevant problem. As far as what is happening in your brain is concerned, creativity is nothing more, nor less, than traditional problem solving.

From this relatively simple foundation, a slew of misconceptions about creativity has arisen. Let’s take a look at five prevalent myths that we may be perpetuating in education.

Myth one: creativity declines with age

In 1968, systems scientist George Land began a longitudinal study that would last nearly two decades. First, Land presented a group of five-year-old children with a simple object, such as a brick, and asked them how many different uses they could think of for that object in five minutes. He then repeated this experiment with the same children at ages 10, 15, 20 and over.

What he found was astounding. At age 5, 98 per cent of the children demonstrated what Land determined was “genius-level creativity”. However, at age 10, just 30 per cent of the children demonstrated this level of creativity. By 15, that had fallen further, to 12 per cent; and by the time the cohort was aged 20 and above, just 2 per cent of them demonstrated genius-level creativity.

The take-home was clear: human beings lose creativity as they age - and, as many have extrapolated, modern education is the primary culprit in killing this creative ability.

As an interesting aside, despite the sheer number of times this research has been cited at educational events, it has never actually been published. It doesn’t exist in academic literature, nor in popular literature. In fact, the only place it seems to be mentioned is in George Land’s 2011 TED Talk.

But let’s assume that this research is, in fact, legit. It takes only a moment of thought to realise that there’s no way it can be accurate. If these results were valid, then why aren’t Fortune 500 companies scrambling to hire preschoolers? Google headquarters should look less like a university campus and more like a nursery.

In truth, adults do not lose their creativity - they simply evolve it. To understand this, it’s important to recognise that, as set out by eminent creativity researcher James Kaufman, creativity comes in three distinct levels:

- Small-c creativity, which requires only personal novelty: knowledge is rearranged to develop ideas that are brand-new to the thinker. For example, a child adding wings to a T. rex.

- Big-C creativity, which requires personal novelty, but also utility and validity: knowledge is rearranged to develop ideas brand-new to the thinker that serve a clear function and are legitimately effective. For example, mixing spices in the cupboard to develop a tasty new seasoning.

- Expert-c creativity, which requires universal novelty, utility and validity: knowledge is rearranged to develop ideas that are brand-new, useful and effective to everyone in the global population. An example would be Einstein systemising the concept of relativity.

Using these three levels of creativity, can you guess why George Land thought all children were imaginative geniuses while all adults were mindless automatons? That’s right: because he tested only “small-c” creativity.

Extrapolating from other published work, it’s likely Land assigned the moniker “genius” to any participant who said at least one thing that no other participant had said (a measure technically called originality).

‘Adults do not lose their creativity - they simply evolve it’

When you ask children to think of different ways to use a brick, they often spit out loads of crazy answers - the majority of which are original, but practically meaningless. For instance, having personally done this brick experiment with children, some of my favourite answers include “it can be worn as a hat”, “it can be used as a birdhouse”, and “it can be thrown into the air to attract UFOs”.

When you ask adults different ways to use a brick, they often supply far more predictable answers, but each of those answers serves a meaningful purpose, in a valid manner. When a five-year-old in Reception suggests wearing a brick as a hat, it’s rightly seen as cute and imaginative; when a 50-year-old at a job interview suggests wearing a brick as a hat, it’s rightly seen as alarming and problematic.

The fact that adults rarely suggest using a brick to contact aliens does not make them less creative; it makes them more discerning and better at vetting the functional utility of creative ideas.

Myth two: creativity is a special skill

As individuals evolve from “small-c” to “expert-c” creativity, it’s common to assume that the process they employ to develop creative ideas evolves as well.

In truth, all creative thinking follows the same basic pattern. The creative process at age 6 is no different from the creative process at age 60. It goes like this:

1. Select a problem

We pose questions like, “How can I irrigate my garden?”; “How can I represent love in musical form?”; or “How many different ways can I use a brick?”.

2. Enter focused thinking mode

We attempt to consciously match our knowledge base to the selected problem; we explicitly rearrange those facts that we deem relevant in an attempt to find a solution.

3. Enter diffuse pondering mode

We step away from the problem (by going for a walk, cooking dinner, taking a nap and so on) and allow our biology to take over. During this period, the brain will use the specific ideas we were consciously thinking about as a “template” to subconsciously find similar patterns within our knowledge base that we may have missed.

4. Re-enter explicit thinking mode

Now, we return to conscious problem solving, except this time we have access to the new set of memories our brain has selected as similar and possibly relevant.

And that’s it. The creative process is the continual swing between focused thinking and diffuse pondering, until a new pattern emerges that matches the original problem state. Importantly, this process is exactly the same for all people; there is no special cognitive skill or ability that some individuals develop while others don’t.

This leads to an important question: what, then, separates “small-c” from “expert-c” creativity?

The answer: knowledge. If creativity is the rearranging of facts to address a problem, then those people with more (and better organised) facts will be able to ask deeper questions and develop more nuanced answers.

Myth three: Google improves creativity

If creativity is simply the rearranging of facts, though, then why spend years building up a store of knowledge? Surely internet search engines, which supply easy access to all the facts in the world, should allow everyone to effortlessly achieve “expert-c” creativity.

Remember: a key step in the creative process is diffuse pondering. During this stage, we step away from a problem and allow our brains to search for relevant patterns and structures that our conscious efforts missed. As you can guess, this diffuse pondering (which is a by-product of basic memory consolidation) can only engage those facts or concepts that already exist within long-term memory. The brain cannot play with information not embedded within it.

This means access to knowledge isn’t enough to drive creativity: stored knowledge is essential.

Stemming from the Google argument, many people believe expertise kills creativity; that the more knowledge a person has, the more predictable their thinking becomes.

To be fair, this is occasionally true in the short term. When experts are given five minutes to solve a problem, they will typically default to traditional solutions that have proved effective in the past.

However, when experts are given hours, days, weeks or months to solve a problem, they will always come up with more creative (read: more useful and valid) solutions than novices.

As you can guess, the reason for this, again, concerns diffuse thinking. True creative ideation requires the engagement of both focused and diffused processes.

Myth four: creativity comes in fully formed bursts

When individuals are asked how they develop creative ideas, their answers almost always come down to hard work and effort. However, when individuals are asked how other people develop creative ideas, the answers almost always invoke sudden insight and instant realisation.

In truth, if it appears that other people’s creativity springs into the world fully formed, this is only because we are on the outside looking in. From an insider’s perspective, the creative process is always a slow, arduous and iterative process of knowledge rearrangement.

Adapting a quote from creativity researcher Robert Weisberg: all creativity springs incrementally from the known - the reason we are struck by the novelty of others’ creativity is that we don’t possess the knowledge they are drawing from.

If “all creativity derives incrementally from the known”, then, logically speaking, we should see a clear process and unambiguous antecedents involved in all creative works throughout history.

‘Creativity is never perfect: it requires significant failure and iteration’

Consider Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater building. This Unesco World Heritage site, located in Bear Run, Pennsylvania, was voted by the American Institute of Architects as the most important building of the 20th century - a shining example of “expert-c” creativity.

With regard to clear process, Wright received the project commission for this house in December 1934 but did not sit down to draw the official plans until September 1935 - at which point he drew the complete blueprint in only two hours. Outsiders often interpret this to mean that Wright had no process, that his creative output derived from sudden inspiration.

However, as Wright explicitly taught his students: “I never sit down at a drawing board until I have the whole thing planned in my mind. One must know every detail - inside and out - before putting pen to paper.” In other words, Wright spent the nine months between commission and completion repeatedly visiting Bear Run, poring over the topography and developing the plans in his mind. He followed the same creative process as all people; he simply chose to document it mentally.

With regards to unambiguous antecedents, each of the three features that make Fallingwater unique had been used previously by Wright: the two cantilevered balconies (which protrude without visible supports) were a standard feature of Wright’s well-established “Prairie house” style; the “invisible” glass window column first appeared in Wright’s Freeman House, built in 1923; and the act of cantilevering an entire structure over a waterfall is something Wright did with a hydroelectric plant at his Taliesin school in 1927.

Granted, these ideas had never before been developed and combined in the same manner as they were at Fallingwater - but that’s what makes it creative: it is an iterative evolution of prior knowledge.

The take-home here is that creativity is never sudden: it requires significant time and incremental effort.

Myth five: creative people never fail

In popular culture, creative individuals are often imbued with the Midas touch. John Galt, Miss Marple, even MacGyver: everything these individuals touch turns to gold.

In the real world, creative quantity breeds creative quality. In other words, those people who pump out the best work are generally the same people who pump out the most work - the majority of which is considered average at best.

For every Hamlet Shakespeare wrote, he also wrote a Troilus and Cressida or Cymbeline. For every poetic line Emily Dickinson composed (“Because I could not stop for Death -/He kindly stopped for me -”), she also scribbled out a dozen head-scratchers (“A Moth the hue of this/Haunts Candles in Brazil”).

Put simply, creativity is never perfect: it requires significant failure and iteration.

All of this shows us that creativity is neither nebulous nor confusing: rather, it is a relatively straightforward cognitive process that all human beings employ regardless of age. In the end, creativity emerges from three basic foundations: knowledge, time and failure.

Implications for schools

So, what does this mean for creativity in education?

Firstly, if creativity relies on knowledge, then by necessity it will manifest as a specific rather than a generic skill. This means those students who write the most creative poems will almost certainly be different from those students who write the most creative lab reports. Those students who produce the most creative oil paintings will almost certainly be different from those students who produce the most creative digital portraits. Even though the creative process doesn’t change between contexts, the knowledge drawn upon does - this inevitably serves to improve or impede creative ideation across varied circumstances.

Secondly, if creativity requires ample time to allow for the shift between focused and diffuse thinking, then any timed exam will be ineffective at assessing creativity. Allowing five minutes to devise novel ways to use a brick might be helpful in determining an individual’s ability to access semantic memories, but seeing as it circumvents the broader creative process, it will be of little use in determining an individual’s creative capacity.

Thirdly, if creativity fails more often than it succeeds, then iteration becomes an essential component of any activity or assignment meant to engage the creative process. When tasks allow students to construct and submit something only a single time, the results will usually be predictable. However, when tasks allow students to resubmit a concept several times following constructive feedback, the results will usually demonstrate stronger creative evolution.

In the end, it’s wonderful that the OECD would champion a greater focus on creativity in education. However, before asking institutions to change their core function and structure, it’s important to specifically clarify the construct of relevance and determine how (if at all) that construct can be meaningfully adopted.

Without specificity, arguments for creativity, curiosity, compassion and the like ultimately engender more confusion than clarity.

Jared Cooney Horvath is a neuroscientist, educator and author

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article