- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Secondary

- Teenage reading: 5 things schools need to know

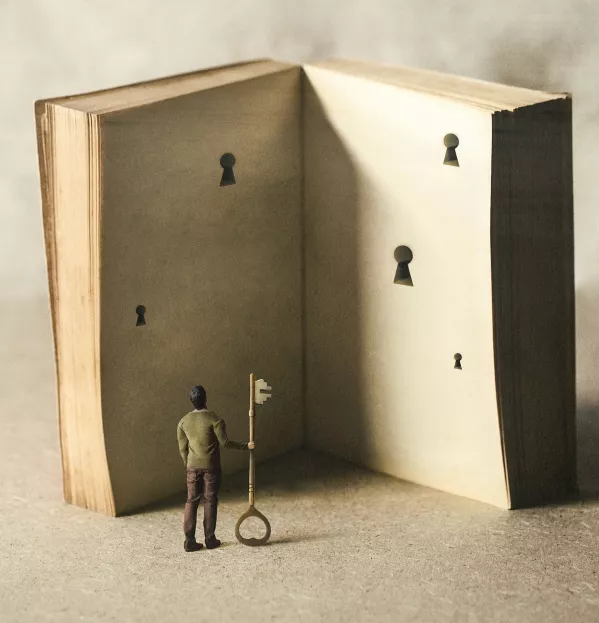

Teenage reading: 5 things schools need to know

Schools are facing a teenage literacy problem.

For years, we’ve been hearing from secondary teachers who recognise that many of their students find reading challenging - but who feel they don’t have the knowledge or resources to support those students in an age-appropriate way.

To help address this, we have undertaken two longitudinal studies and a set of experiments to find out more about teenage reading, how it develops, how it relates to spoken language abilities and how we might encourage students to read more.

Most recently, we set out to respond to two particular concerns that are widely held by teachers: that there is a “slump” in reading and vocabulary during the summer that marks the transition from primary to secondary school, and that limited vocabulary is a barrier to learning for many students.

In our Reading and Vocabulary project, the results of which are published today, we followed children longitudinally from Year 5 to Year 8 and combined this with experimental research.

Here’s what we found.

There is no transition slump

We used a longitudinal research design to track reading and vocabulary progress in a group of children as they made the transition from primary to secondary school. Importantly, we used the same reading and vocabulary assessments over time, and we compared the transition summer holiday to a non-transition summer holiday.

When we analysed our data, we found that there was no transition slump - reading and vocabulary did not stall or go backwards during the transition summer. Instead, there was significant progress, and this progress resembled another non-transition summer holiday.

Clearly, though, the demands on reading and vocabulary increase as children move up the school system, indicating that school transition reflects a jump in expectations, rather than a slump in skills and knowledge.

Children from poorer backgrounds aren’t disproportionately affected

We were concerned that the pattern might look different for children from lower socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds. This was not the case: transition didn’t disproportionately disadvantage these children, compared to their peers from higher SES backgrounds.

However, we did see clear SES differences on most of our assessments, with those from lower SES backgrounds tending to gain lower scores on vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension. These differences were persistent over time but stable, rather than increasing over time.

SES differences weren’t observed for word reading proficiency, which is encouraging and suggests that the SES differences observed earlier in primary schooling have been addressed through effective teaching of early reading.

Reading and vocabulary skills are closely linked

Our longitudinal data revealed that many students enter secondary school with vocabulary and reading needs. We sought to understand the links between attainment in vocabulary and reading by combining longitudinal findings with an experimental approach as a gold standard for understanding causal relationships in development.

Here, we showed that reading drives progress in vocabulary directly, and also indirectly through the amount that children read. In other words, how good you are at reading directly helps you learn about words and being a better reader means that you are likely to read more and therefore learn more about words.

Our experimental study backed this up, showing that the number of times a child reads a particular word during leisure reading is directly linked to the amount that they learn about that word.

So, what should schools take from all of this? Bringing the findings of our latest project together with our other research, we have five key points for schools to consider:

1. Reading is not a primary school issue

We can’t “fix” reading and vocabulary in primary, because some needs are persistent and/or emerge later, when school becomes more challenging. In addition, the secondary curriculum places increasing demands on reading and vocabulary and expects students to read independently. We need to support all students to ensure that they can continue to meet these challenges, and to read independently and more critically.

2. Two-step screening can help

Many students enter secondary school with reading and vocabulary needs. We have developed a two-step process that combines the screening of all students with individualised diagnostic assessment for some to identify needs with confidence and align them with appropriate support and interventions.

3. Teacher training must be prioritised

Reading and vocabulary attainments are extremely variable in secondary school. While there is progress in reading and vocabulary, the variability among students is huge. This presents a challenge for teachers to provide instruction that caters to this variability. It also means that as students move up secondary school, their progress may not keep pace with the rising challenge of the curriculum.

Secondary teachers tell us that they benefit from professional development around reading, and from knowing which students in their classes have significant needs.

4. Don’t worry about the ‘transition slump’

There is no transition slump, but rather a shift in challenge and context. This shift is partly driven by emphasis in the English curriculum changing from learning to read in primary school to reading to learn and the critical appreciation of texts in secondary.

Primary and secondary teachers tell us that they benefit from cross-phase discussions and that greater understanding of the other context enables them to better support students across transition.

5. Reading for pleasure matters

“Can” does not mean “do”, and “do” does not mean “can”. In secondary school, the amount that students read declines and many students who can read well do not do so in their own time. On the other hand, students with significant reading needs will find it hard to access secondary-level texts.

We must therefore embed robust identification and support for reading needs within a rich culture of reading for pleasure.

We have learned a lot, but there is still much more to find out about supporting reading at secondary school, both in terms of the universal offer and targeted support for those who find reading challenging, or are not motivated to read.

Evidence for effective approaches is still sorely lacking. We need collaborative research where teachers, students and researchers work together to understand not only what will be effective, but also what will be feasible in school, and acceptable to young people and teachers.

Professor Jessie Ricketts is director of the Language and Reading Acquisition (LARA) Lab at Royal Holloway University and Dr Laura Shapiro is a reader in the School of Psychology at Aston University

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article