Prior to the government U-turn over A-level grading, some schools and colleges were left scratching their heads over calculated grades that seemed far lower than what they would have predicted for their students.

In a new blog for FFT Education Datalab, statistician Dave Thomson explains one reason why this was the case.

GCSEs 2020: 3 things to expect in this year’s results

A-levels and GCSEs U-turn: The end of the algorithm?

Exclusive: Ofqual missed A-level private school bonus

Schools were expecting somewhat higher results for their 2020 A-level cohorts because the GCSE average point score of the group had increased. The group seemed to have higher prior attainment, and would therefore achieve higher grades in their A levels, the theory went.

However, the measurement by which prior attainment was calculated relied on an average GCSE point score. As Mr Thomson writes, the “average point score is simply the average grade in reformed GCSEs”.

“So if you took 10 GCSEs and you received grade 8 in five of them and grade 7 in the other five then your average would be 7.5,” he adds.

However, the A-level cohort in 2019 took fewer reformed GCSEs, because 2017 was the first year that reformed GCSEs in English and maths were introduced.

The Department for Education has devised a conversion scale for the old A*-G grades to be mapped onto the new 9-1 scale, with an A* grade equating to 8.5, and a B to a 5.5, for example.

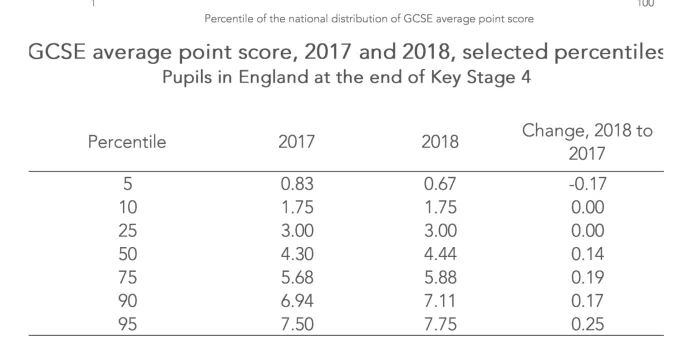

However, Mr Thomson notes that “because the method of equating A*-G grades to 9-1 grades used by the Department for Education is not directly equivalent, it appears that the 2020 cohort has slightly higher prior attainment overall than the 2019 cohort”.

At the upper end of the GCSE grade distribution, GCSE average point scores were around a fifth of a grade higher.

While he writes that this “doesn’t sound like much”, it had consequences for how schools calculated A-level grades based on prior attainment.

Using a hypothetical scenario where a group of 20 A-level maths candidates had an average GCSE point score of 8.1 in 2020, the Department for Education’s transition matrices would have predicted that 48.4 per cent of the group would gain an A*.

However, “GCSE average point scores were around 0.2 points higher in 2018,” Mr Thomson notes.

If the GCSE average point score for the group is lowered by 0.2 percentage points, just 21.6 per cent of the cohort would gain an A*.

“To get around this problem, Ofqual age-standardised the GCSE average point score of each cohort when making adjustments based on prior attainment,” he writes.

“However, no details have been published on the age standardisation process to the best of our knowledge,” he adds.

For schools using the DfE’s matrices to make their own calculations of expected grades, this explains why calculated grades may have been lower than expected: prior attainment looked like it had increased, but only because the cohort in 2020 took more reformed 9-1 GCSE subjects.