- Home

- Long read: Do classrooms need standing desks?

Long read: Do classrooms need standing desks?

“Most people in class like sitting next to me, because I’m good at football,” says seven-year-old Luke. “Then they want to talk to me. And sometimes I don’t want to talk to them. So I like sometimes being on my own.”

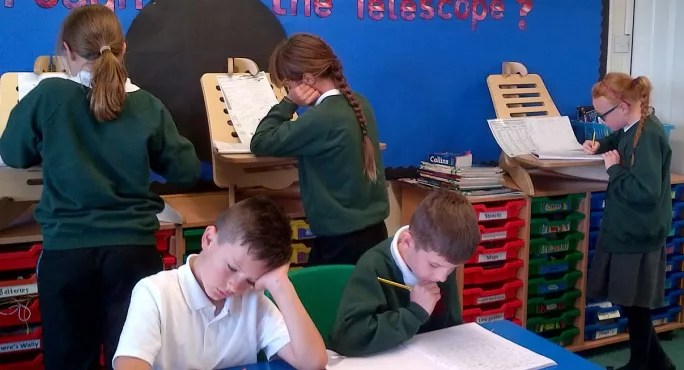

Luke is a Year 2 pupil at Kewstoke Primary School, in Somerset. He is standing at the far wall of the classroom, slightly apart from other pupils, at what appears to be a large wooden lectern.

In fact, it is not a lectern at all. It is a standing desk: a vertical piece of slatted wood, which sits on top of a work surface. A single, horizontal piece of wood is fixed into one of the slats - the slat chosen varies, according to the height of the child - and this provides a desk surface on which to read and write.

Standing desks hit the news recently, when a group of health campaigners, led by celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, called for pupils to stand at their desks during the school day, in order to tackle obesity. Dr Rangan Chatterjee, of BBC 1’s health-advice series Doctor in the House, said that standing desks could contribute towards weight loss, by using up more energy than conventional desks.

In fact, standing burns only slightly more energy than sitting - but the desks offer a range of other benefits to learning, behaviour and pupil wellbeing.

Kewstoke, an 86-pupil village primary, is already using these desks, as part of a deliberate strategy to help pupils discover how they learn best. There is one in each of its classrooms, except for Reception, where pupils spend a fair amount of time on their feet anyway.

In the Year 1-2 classroom, Luke leans on the standing desk, diligently writing science-lesson sentences into his exercise book: “Windows are made of glass.”

He chews on his pencil. “When I’m leaning on a table, sometimes it can be cold,” he says. “But this desk doesn’t get cold, because it’s wood.”

He pauses. “I like standing up. It just makes me tired, so when I get home I get a good night’s sleep. It makes me more tired than being in the playground - it gets rid of your energy more.”

‘The fidgety children’

But Daniel Bingham, coordinator of ongoing research into the feasibility of standing desks in the classroom, conducted by the Born in Bradford Study and Loughborough University, argues that this is no more true when it comes from a TV doctor than when it comes from a seven year old.

“The point of having these tables is that they reduce sitting,” he says. “It’s nothing to do with obesity. The amount of energy we use by standing rather than sitting is very small.”

In fact, increasing the amount of energy expended by pupils was not the primary reason for ordering the desks at Kewstoke, according to headteacher Sarah Harding. Instead, they form part of a policy to make sure that children are comfortable when they learn. Use of the desks tends to be limited to those pupils who, Harding says, “in the old days would have been called the fidgety children.

“Some children cannot sit still for long periods of time. That makes them frustrated, and they can’t concentrate on their learning. And we want all children to do well and to make good progress.”

Kewstoke pupils understand that there are some occasions when standing is not appropriate: they know, for example, that they will be expected to sit still for 45 minutes while taking their key stage 2 tests. And they know that standing desks will not be an option at secondary school.

At Kewstoke, however, pupils are free to stand, sit, or kneel up on their chairs. “Children learn better in different positions and at different times of the day,” Harding says. “Our school is all about choice, so the children understand themselves and what they need. So, if they need to get up and stretch their legs, then that’s what they can do.”

Obviously, she adds, it would be disingenuous to suggest that the standing desks had eliminated all misbehaviour in the school. But it has reduced notably: children are no longer misbehaving simply because they would rather be standing up and wriggling than sitting at their desks. This is borne out in academic research: earlier this year, US researcher Mark Benden, of Texas A&M University, told Tes that children became restless and inattentive following prolonged periods of sitting. Standing desks therefore reduced disruption and poor behaviour, Benden found.

‘You see the nice view’

In the Year 3-4 classroom, the standing desk has been positioned underneath the windows, so that pupils can look out over the Somerset hills. And beyond those hills, across a mud-brown bay, Cardiff’s waterfront district is visible in the distance.

“Sometimes, it’s not nice when you’re sitting down,” says eight-year-old Year 4 pupil Imogen. “Sometimes it makes you want to fidget, and then you get distracted. Sometimes, it’s just nice to do your work.

“The standing desk makes me want to stop fidgeting, and it makes me concentrate on my work. And, because of the position of it, you can’t see if anyone’s being silly, and they don’t distract you.”

Eight-year-old Josh wanders up to join her. “And, if you’re angry, it makes you calm down,” he says. “Because you see the nice view.” He pauses, and glances over at the condensation-misted windows. “Not when the window’s steamed up. Then you can only see steam.”

Some pupils use the desks the way that office-bound adults might use a tea break: as a five-minute opportunity to stretch their legs. Others stay for longer. Most, Harding says, will spend a maximum of 20 minutes standing, before returning to their seats.

“If you use it too much, then your legs can ache,” Josh says. “That’s the only downside. If my legs didn’t ache, I’d spend all my time there.”

There are a range of standing desks on the market. Some of the higher-tech, electronically adjustable versions cost more than £1,000; Kewstoke’s cost £187 per desk.

“I Googled ‘I want a standing desk’, and a company came up called I Want A Standing Desk,” says Harding. “They look nice, they fit in, and they’re very easy to adjust. Children can self-adjust them.”

‘A desk of one’s own’

Initially, five trial desks were set up in the Year 5-6 classroom. Teacher Fiona Mann tried placing one at each group of tables, so that children could stand next to their sitting classmates.

“I think they found children standing up at the table to be - it wasn’t a feeling of everybody working in the same way,” Mann says. “So that difference of work height affected their concentration, and it affected both sitting and standing pupils in different ways.”

Now, the classroom only has one standing desk, placed facing one of the side walls. “If I want to concentrate on English, and I want to do really good work, I go and stand there, says 10-year-old pupil Millie.

Next to her, 10-year-old Ruby looks up from her own work. “I use it if I want to be on my own, without sitting next to Millie.”

Millie nods. “I can be a bit annoying. But only a little bit.”

“I think sometimes it’s good to be quiet,” says Ruby. “But it’s really hard for me to be quiet. You can concentrate more if you’re looking at walls.”

Millie, meanwhile, uses the wall displays for inspiration: “Just looking at something different, not to do with your work, can be useful.”

After all, says Harding, adults wanting to concentrate on their work will often seek out somewhere quiet where they can focus. And most adults recognise the need to look up from the computer, gaze out the window for a few minutes, and then go back to work. Why should children be any different?

“It’s a bit of Virginia Woolf time,” she says.

Mann smiles. “A desk of one’s own.”

Load-bearing

But the new desks are not simply a place to stand and stare. Researcher Daniel Bingham says that their main purpose is to show children that there is an alternative to sitting down for large chunks of the day.

There is growing evidence to suggest that sitting for more than an hour at a time can lead to a spike of insulin in the body, he says. This then has the potential to increase cholesterol, and may be linked with diabetes and respiratory problems.

“It’s as simple as: if you watch TV at night, stand up every half hour, and you don’t have such a negative effect,” he adds. “Children spend a long time in the classroom, but they are environments to sit down in.

“A couple of standing desks can just change that environment. Not drastically: we’re not forcing children to stand up. But it’s giving them an option. Saying: a standing desk can be beneficial for your posture. Sitting can be bad for your posture. It’s educational.

“It’s about getting to children young. Just changing the way people think about work. You don’t have to sit down all the time. You can stand at the kitchen counter and do some work there.”

Whether Kewstoke pupils’ posture is improving through use of the standing desks is debatable: Year 3 pupil Josh leans his elbows heavily on the desk as he writes.

“Josh likes to lean,” says Year 3-4 teacher Katie Bray. “He’ll often ask if he can use the standing desk today, and I think it’s because he likes to lean - to bear his weight. Often, when he comes in from play, he wants to stand and lean, rather than sit. It’s about energy.”

But, despite his leaning, Josh is proving Bingham’s point about changing how pupils think. “I’d like to have a standing desk at home,” he says. “When you sit down all the time, your butt kind of aches.”

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters