Is it OK to call my students ‘sweetheart’?

Safeguarding is the most significant responsibility all of us have when working with young people. We work hard to spot signs. We identify potential lapses in procedure in order to protect and provide a safe environment where students can define their boundaries clearly. And we call out anything where we think there may be the slightest possibility that this could be compromised.

But do we run the risk of losing something important as we try to police our language choices around young people? Is it acceptable to use terms of endearment in the classroom?

Relationships are at the heart of every school. I was known as one of the strictest teachers in my school, where routines were constantly reinforced, boundaries carefully established and revisited, and the expectations of both work and behaviour were high for all.

However, when welcoming my students into the classroom, I would refer to them as “hedgehogs”, “meerkats”, “pumpkins” and occasionally “armadillos” (don’t ask). Often, they were “my wonderful people” or “my superstars”.

Terms of endearment in the classroom

These names are silly, unexpected and quirky, falling off the tongue with ease. While I tended to avoid gendered terms, this spoke volumes about the relationships we shared and the overall tone of the lesson we were about to have. We went on adventures in English and who knew quite where these stories would take them. It became something they identified with me.

I have always worked in secondary school, and these welcomes were usually met with quizzical looks, sly grins and sometimes outright laughter. Laughter that was shared between us. There was no offence intended and none ever taken - but I do think there are a few things to consider here about our choice of language.

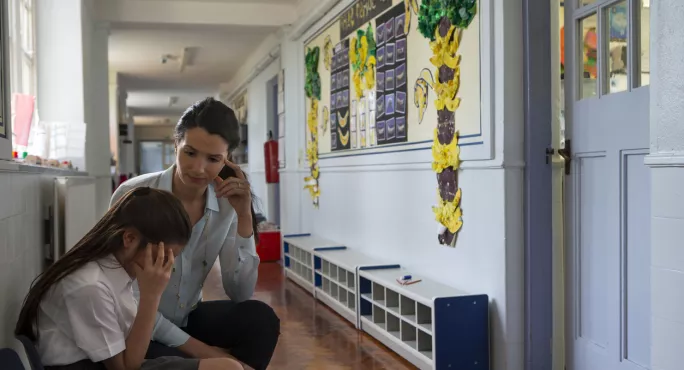

First, it was usually a group welcome, as opposed to an individual address. Sometimes when I had a distressed or anxious individual in my class, who was frustrated about work or something outside the lesson, I’d ask, “How can I help you, my lovely?” The intention here was to defuse some of the tension and present myself as non-threatening.

But I generally tended to avoid individual terms of endearment as I didn’t want to blur boundaries, especially as students can be keen to see us as a friend rather than an authority figure.

Secondly, it is important to consider the specifics of the relationship. I had worked for a long time in the school. Students had known me for many years, sometimes even before they arrived at the school as students, and these relationships had been built up carefully over time.

Safeguarding students - and teachers - from any misunderstanding

This, coupled with the clear boundaries and expectations that I mentioned earlier, meant that there was little room for ambiguity. As kind as I would be to students on a one-to-one basis, I was always careful to ensure that my language safeguarded me, and them, from any possible misunderstanding when working alone.

There are regional differences to consider, too, when talking about language. I was down South, where stereotypically people are more aloof and make automatic choices in their language that could be different from elsewhere.

In other areas, terms of endearment are woven throughout everyday speech. When it is part of the dialect, not saying “love”, or “hen” when addressing someone could seem out of place, and even quite rude. Conversely, a well-placed “love” in a sentence in my hometown could be regarded as a downright declaration of war.

Other terms such as “babe”, “darling” and “sweetheart” are more problematic, with their associations with gender roles and misogynist discourse of old, and many will quite rightly suggest that these should be confined to the bin.

But, even then, context will be important. When a distressed five-year-old, sobbing their heart out for their mum, hears, “Come on, sweetheart, let’s go and see your friends,” they may be comforted on hearing a familiar word suggesting care and concern. It could well be just the thing they needed to hear at that moment.

Ultimately, when we consider our language in the classroom, it is important to think about relationships, context, the location to allow for regional variation, and the structures we have in place to ensure clarity in all we say and do.

We have a duty to protect, and a duty to ensure that we maintain clarity for students who may not necessarily understand the nuances of these words. But we also have a duty to show our care for them, and terms of endearment may well be one way we can do that, without compromising on anything else.

Zoe Enser is lead English adviser for Kent. She tweets @greeborunner

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters