- Home

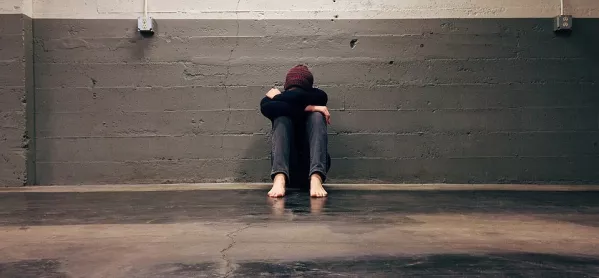

- ‘Teachers are constantly forced to fill the void as the gaps in children’s mental health services grow’

‘Teachers are constantly forced to fill the void as the gaps in children’s mental health services grow’

“Money is so tight that a single suicide bid by a student is no longer considered serious enough to trigger further intervention from outside the school.”

A Manchester headteacher mentioned this to me last week, and it has been echoed by many others since.

It is sometimes hard to make education funding cuts concrete for people - certainly compared to NHS cuts, for example - but I think this does so. Ironically, talk of billions lost doesn’t really mean much to most of us; what do the billions mean for vulnerable young people in distress?

Well, this is what they meant at a special school in the south of England: a seventeen year old autistic girl with learning disabilities refused to go home and was still on site at school at 5am, supported by three staff who remained from the previous day.

The social services team were unable to send anyone out to support her grandmother who repeatedly came to the school. The medical team would not instigate psychiatric support for the situation, which had begun at half three the previous afternoon.

Running out of options to secure proper care, at half five the police arrested her on the pretext of public order to enable forcible removal then dearrested her into the care of her grandmother once out of the school building and in car park. The three staff were back at work for a normal school day at quarter to eight.

It is surely heart breaking that cuts in social and medical resources are eventually forcing our most vulnerable young people into the criminal justice system in order to get some help.

In another case, a father had threatened to kill himself and his children if he was refused asylum. The school was told that the risk wasn’t high enough to pass the threshold for intervention until asylum had actually been refused.

There was also the maddening situation of a child whose mental health needs were deemed too challenging for the school-based counsellor at the lower tier of support (and therefore she was advised by the CAMHS not to engage) but not complex enough to pass the threshold for the next tier support external to the school.

These examples also illustrate another inconvenient fact. It is not just a matter of the money going into schools, tight as that is. Schools do not stand alone; they rely on a network of other services and support.

If you cut these services, you are cutting school resources as they have to plug the gap themselves. The front line is not actually protected.

Local authority budgets have been cut dramatically over the last five years and as a result, the thresholds for intervention in social care and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) have risen dramatically.

Infant age children in particular are often not considered appropriate for intervention. Which is a huge shame as early intervention could help limit a lifetime of troubles - prevention is not only better than cure but also cheaper too.

Place2be tell us that primary schools are increasingly using pupil premium money to fund such support.

Similarly, education and health professionals battle over whether specific needs are properly defined as medical or educational - and who should pick up the funding. At the same time, secondary schools are cutting back on in-house counselling services as they struggle to manage the real terms budget cuts.

In the face of such significant challenges, warm words and short term schemes are simply not enough.

A school-only system

The attention given to mental health this week is hugely welcome but it needs to be backed by the resources in schools and in the services schools use. This is not a matter for a one-off training intervention; job done.

I like the idea of a mental health lead in schools, for example, but staff once trained have to be employed and given time away from other duties to support students and colleagues.

They need to be able to access advice and support and when vulnerable students are identified, they need specialist help before rather than after they hurt themselves.

While staff are doing these things, if they are to do them well, they will not be doing any other of the multitude of responsibilities we see fit to ask of schools.

When confronted by deep and complex problems, it has become far too easy to delegate the task to schools and consider it done. But schools are struggling to deliver their core teaching function in the face of real terms budget cuts.

They lack the capacity to pick up the pieces for other services.

A school-led system must not degenerate into a school-only system, using subtle flattery to disguise the burden being imposed.

A school is most successful as a place of learning when it works within the context of high quality social care, and health and youth justice services (among many others). Not to mention a middle tier which can broker support and plan strategically for places and staffing.

Different institutions should focus on their strengths and work together across boundaries to meet student needs. Have they always been good at this cross-sector working? No, but the answer is to improve it not end it.

The trouble with schools, though, is that they are physically present in the heart of the community, conscientious in their duties and largely trusted by those they serve. This makes them a sitting duck for bright ideas to tackle intractable problems.

And, because schools know they cannot teach when children are scared, hungry, distressed or unwell, they do what they can to fill in the gaps.

It is a credit to teachers that they do so; it is not a credit to the system they work within that they must.

Russell Hobby is general secretary of the NAHT headteachers’ union. He tweets as @RussellHobby

For more columns by Russell, view his back-catalogue.

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters