GCSE results day 2022: 6 key insights you need to know

GCSE results day 2022 came and went in a blur and - like with A-level results last week - marked the first relatively normal results day since 2019.

However, with glide paths in place to try to undo the grade inflation we saw during the pandemic, national reference test data and the usual mix of grade boundary changes, there was a lot to unpick as the results were unveiled.

So with time to digest the swathes of data that were released yesterday, we have identified some of the major trends to provide the key insights that those in education need to know about ahead of the new term.

Find out about GCSE results day 2023

GCSE results 2022: The key insights

1. National Reference Test data proves the power of teachers

During the pandemic, concerns were rightly raised about how far young people would fall behind in their learning.

However, National Reference Test (NRT) data released alongside the GCSE results suggests that the impact may not be quite as bad as we feared - chiefly due to the hard work of teachers to tackle perceived learning loss.

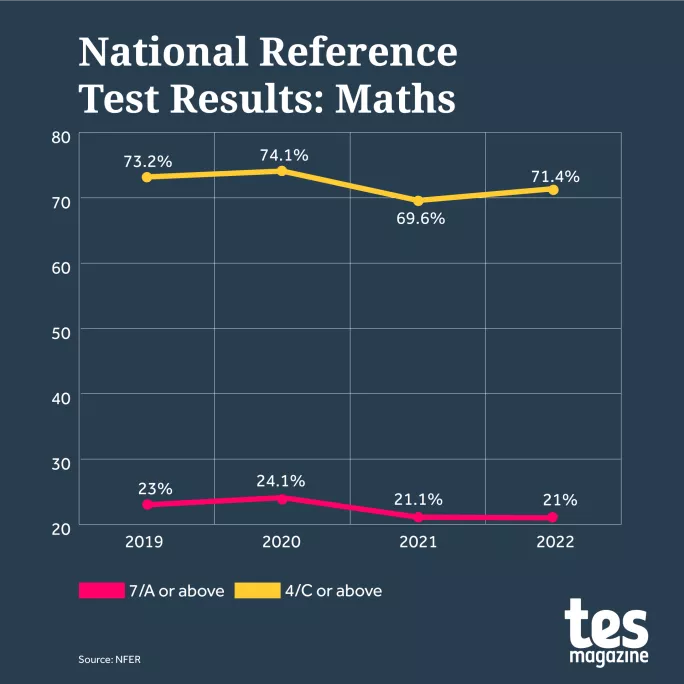

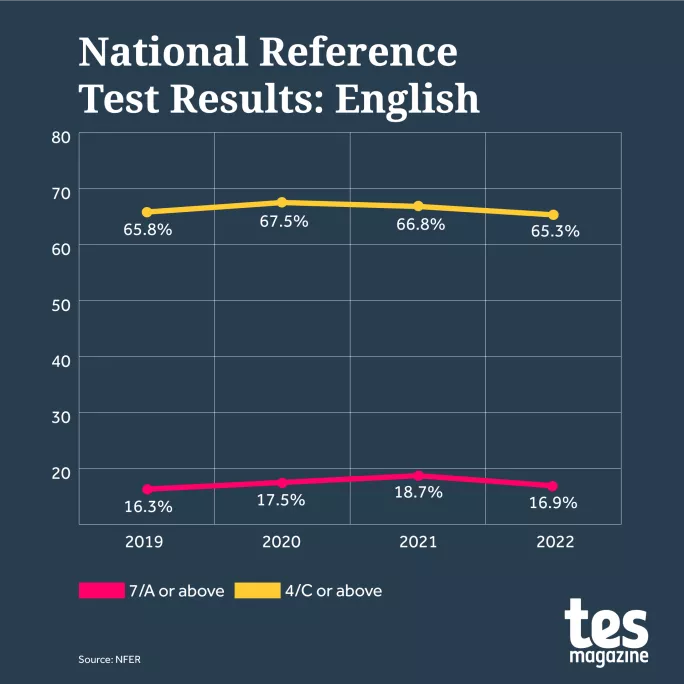

The NRT is taken by a sample of students in a range of schools every year and is designed to gauge the ability of the exam cohort in English and maths. The exams regulator, Ofqual, then uses the information when deciding the grade boundaries for GCSE.

Unlike with GCSEs, the NRTs still involved in-person tests in 2020 and 2021, and so they provide a better insight into the impact of the pandemic on each cohort.

Not only that but in contrast to the GCSE exams, for which content was reduced and advance information was shared this year, the NRTs have had no adjustments made at all.

So how did students do? The official National Foundation for Educational Research report concludes that there were “no statistically significant changes in English” compared with before the pandemic. Although the maths results were “statistically significantly lower”, the difference is perhaps less than what might have been expected given the disruptions experienced by the cohort.

Professor John Jerrim, a lecturer in education and social statistics at University College London and research associate at FFT Education Datalab, said that overall this showed the positive impact of teachers on students this year.

“I think teachers and schools deserve a lot of credit for their efforts over the last few years,” he says.

“The results from the NRT give us our best indication of learning loss and subsequent catch-up in secondary schools. The pandemic obviously had the potential to cause huge educational damage. From the NRT, I think what we can see is the huge efforts the education community has made over the last few years.”

Another reason why the results look so promising could be the age of the students when the pandemic began, says Jerrim.

“This cohort would have been in Year 9 when the pandemic hit England, and so would have had more capacity to learn independently than younger children,” he explains.

But why might English have fared better than maths? Jon Andrews, head of analysis at the Education Policy Institute (EPI) think tank, thinks this can be explained by what happened when schools switched to online learning.

“While English attainment has held up over the course of the pandemic, pupils’ mathematics performance has suffered…this may be as a result of English being more accessible to study and learn while learning from home,” he suggests.

However, before we can draw any firm conclusions we need more data, says Jerrim, who believes that the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) will give us a better idea of how the pandemic has impacted young people in England.

Andrews agrees, cautioning against drawing comparisons between year groups.

“It’s difficult to make direct comparisons between key stages and the relative magnitude of lost learning,” he says. “Older children would be better equipped to study and learn independently but our latest learning loss analysis suggested pupils at the start of secondary school still had more catching up to do than those at the end of primary.”

Over time, as teachers become used to exam specifications, performance in exams tend to improve - this is called The Sawtooth Effect. Could the NRT be affected in the same way?

Possibly, says Ofqual’s research chair, Paul Newman.

”As the National Reference Test (NRT) was introduced in the same year as changes to GCSE English and maths, it is possible that any rise observed in the NRT results during the first few years could be put down to a sawtooth effect,” he explains.

However, Newman does not believe the results we are seeing can be attributed to this.

“We didn’t see any rise in the NRT results for English during the first few years, so there is nothing to explain there, in terms of either a sawtooth effect or a genuine rise in attainment,” he says.

Speaking generally about the results, Newman says while the results in English and small decline in maths represent “the overall cohort position” it does not negate the very real impact the pandemic will have had on their studies as, “they will have felt the impact of the pandemic in different ways”.

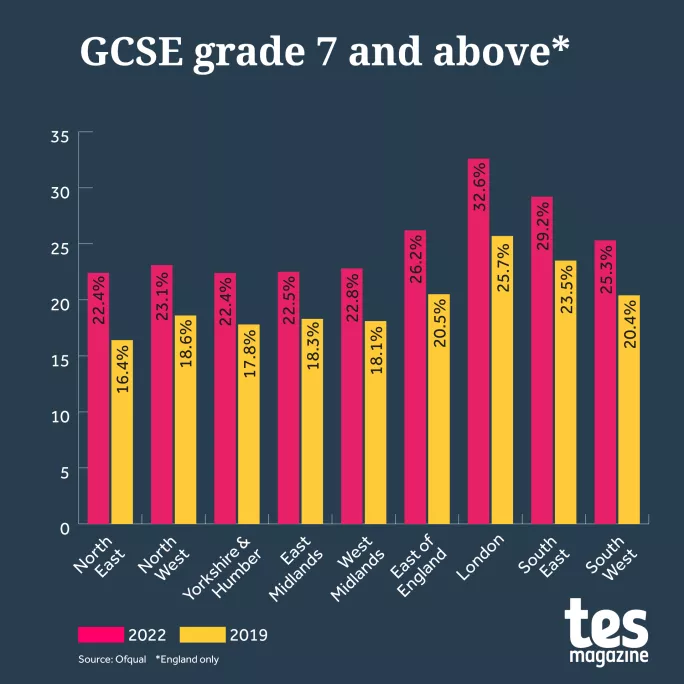

2. The North-South divide isn’t narrowing

Regional differences are always watched with interest in exam season - and this year was no exception.

The big issue is the size of the gap between regions in the North and the South of England, which actually increased this year compared with 2019, when GCSE exams were last held.

Most strikingly, in the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber, 22.4 per cent of students received GCSE grades at 7/A and above - the lowest figure of all regions.

That is a huge 10.2 percentage points lower than London, which had the highest proportion of GCSE grades at 7/A or above (32.6 per cent), and 6.8 percentage points lower than the South East at 29.2 per cent.

This disparity aligns neatly with insights from FFT Education Datalab that show that the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber had the highest Covid absence rates across Years 10 and 11 at state schools this year, with rates over 14 per cent.

Conversely, London had the lowest absence rates among these year groups at below 12 per cent.

Given these different absence rates, a regional imbalance in outcomes was expected, and plans to adjust exam grading in GCSEs and A levels by area were mooted - but never got off the ground. The impact of this is now clear to see.

However, while it would be easy to blame the pandemic for this, the reality is that big regional disparities existed before the pandemic - for example, the gap between the North East and London was 9.3 per cent in 2019.

This is an issue that has dominated education debates for a long time. Whatever “normality” returns to schools in the years ahead, tackling this problem needs to be a top priority for policymakers.

3. The gender split remains just as stubborn

The split between the performance of girls and boys at GCSE has been a theme of results days for many years - and so it remained this year, with the data showing that the gap between the two groups is still significant:

- 8 per cent of female entries at GCSE achieved grade 9/A* compared with 5.5 per cent of male entries.

- 30 per cent of female entries achieved grade 7/A or above compared with 22.6 of of male entries

- 76.7 per cent of female entries achieved 4/C or above compared with 69.8 per cent of male entries

- 98.8 per cent of female entries achieved 1/G or above compared with 98.0 per cent of male entries

The gaps here broadly match those from past years, pandemic-affected and not, suggesting that despite the upheaval of the past few years, the attainment of girls remains persistently higher than boys’ - an issue that many have argued needs to be solved.

Ofqual data also shows that for that select group of students that achieved all grade 9s in the exams they sat, 67 per cent were female entrants and 33 per cent were male. This gap has widened since last year, when it was 64 per cent against 36 per cent.

However, the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) did say that for certain subjects like maths and physics, male entries were higher at 7/A compared with female entries.

While Ofqual advises schools not to look at their own data for boys and girls as the sample sizes are too small, it seems likely that many schools will wonder how they can try and close this gap in the year ahead.

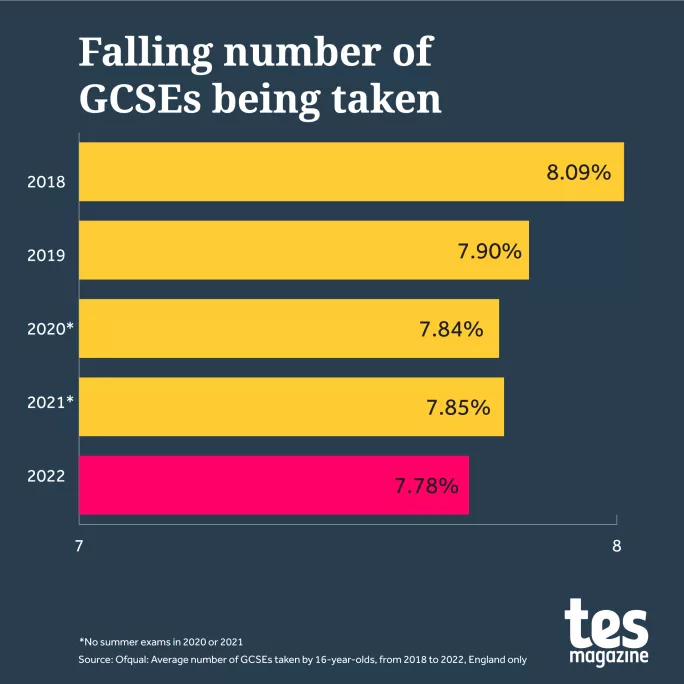

4. The average number of GCSEs being taken has fallen

An interesting observation is that 2022 marks another year of decline in the average number of GCSEs being taken by students aged 16 - a trend that the pandemic did little to change.

Overall, in 2018 an average of 8.09 GCSEs were sat by students. However, by 2022 this has fallen to 7.78.

The most popular number of GCSEs to take remains nine, with 163,050 (26.2 per cent) taking this many in 2022 - although this was down from 165,590 last year (27.1 per cent).

The number of students taking 10 also fell, from 78,850 to 75,850.

Meanwhile, the numbers taking five, six, seven or eight GCSEs all slightly increased.

This cannot be explained by student population shifts, as the number of 16-year-olds taking exams in 2022 was up on 2021, rising from 613,100 to 622,350.

Jerrim says the decline seems a “rational response to the pandemic” as schools and students would have focused on doing well in a core number of subjects, rather than stretching themselves unnecessarily.

“These kids would have been in Year 9 when the pandemic hit before they would have chosen their subjects [so] better to focus on getting better GCSEs in a slightly smaller number of subjects than being spread too thinly,” he says.

Andrews offers a similar view that schools may have been focusing on ensuring success in a smaller number of subjects - but says that the issue deserves further investigation

“As more data emerges, it may be worth exploring whether there are particular school or pupil groups that are particularly affected,” he says.

5. The decline in MFL is concerning - and confusing

Despite provisional entries published earlier in the year implying that there would be an increase in the number of students taking modern foreign languages GCSEs, the results tell a different story.

Because, while there has been an increase in the number of young people overall taking GCSEs, there has been a decrease in entries in French, German and Spanish, with the decline in German particularly notable, falling from 41,222 entries in 2019 to 34,966 in 2022.

This dashed hopes that we might have seen an improvement in the number of schools entering students for the English Baccalaureate subject combination - as MFL has long been the cause of the failure of the government to hits its ambitious EBacc targets.

Furthermore, the difference between provisional and actual entries was significant - it was expected that 116,355 students would be taking Spanish, but the JCQ data from yesterday reports that this dropped to 107,488.

Helen Myers, president of the Association for Language Learning (ALL), says the decrease in exam entries when compared with the provisional numbers submitted to exam boards in April was “unexpected”, and something the organisation would be asking for information about.

“The difference was noticed when the JCQ numbers were announced,” says Myers. “ALL would ask that Ofqual and JCQ explain the difference.”

Dave Thomson, chief statistician at FFT Education Datalab, also says he was “baffled” by the decline.

However, there is some good news in that Ofqual has implemented an “uplift” to French and German to bring them in line with Spanish.

This was done because there have been concerns that grading in languages is too harsh compared with other subjects. By uplifting, Ofqual hopes, in part, to encourage more students to study languages.

This plan has translated into the proportion of students scoring a grade 4 or above in French rising by 8.4 percentage points.

This means over 10,000 more students passed in 2022 than in 2019.

For students achieving top marks, the uplift is particularly notable. Grade 9s have risen from 5.1 per cent in 2019 to 10.3 per cent in 2022.

We see a similar picture for students taking German, where the number scoring a grade 4 and above has also risen, this time by 7.7 percentage points to 83.5 per cent.

German top grades have increased proportionally even more than French, with 12.4 per cent of entrants collecting grade 9s in 2022 compared with 5.8 per cent in 2019.

This means the total number of students scoring grade 9 has increased by 1,945 students to 4,335.

With more students hitting passing grades, will that shake MFLs’ image of being “tough” GCSEs and encourage more students to opt for a language?

Thomson isn’t optimistic: “The changes do not go far enough. Bringing French and German in line with Spanish will still leave MFL more severely graded than other subjects, particularly if Ofqual is only going to consider grades 4 and above [as a pass].”

For example, in 2019 students were more likely to achieve grade 3 or lower in MFL than in English or maths, and that applied to Spanish as much as to French and German.

6. Grade boundary moves less than expected

As part of Ofqual’s plan to return to the grading standards before the pandemic, grade boundaries were subject to “more generosity” during the awarding process.

So, in theory, a student would need fewer marks to secure a grade 4/C or 7/A than in previous years.

However, when grade boundaries were published as part of yesterday’s GCSE results, schools noticed that for some subjects grade boundaries appeared to be the same as in 2019, and for some exam boards they were even higher.

As you can see in the tweet above, for Pearson some grade boundaries remained the same or only moved by two marks. In AQA’s case, the grade boundaries actually increased.

This may look like the higher grade boundaries meant it was harder to get higher grades this year - but due to the way grade boundaries work, this is not true.

The reason behind the higher grade boundaries could be explained by the mitigations exam boards put in place, such as advanced information and reduced content. These changes may have resulted in more students scoring well on the paper compared to previous years.

And that isn’t the only factor that can influence grade boundaries. If the papers themselves are comparably more accessible than in previous exam series, then this will result in an adjustment of the grade boundaries to ensure consistency over time.

During the awarding process, Ofqual would have made comparisons between exam boards and papers from earlier series to decide the grade boundaries. You can read more about the awarding process and how grade boundaries are decided in our blog here.

So what caused the higher grade boundaries during a year when grade boundaries were generally lower overall?

Tom Middlehurst is the curriculum and assessment specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL). He believes it was the way the advanced information differed between subjects that can explain the variation in the movement of grade boundaries.

“[The higher marks were] not necessarily because the papers were easier but possibly because the students were well-prepared as a result of the advance information that was available,” he says.

“The grade boundaries in these subjects were actually set at higher points than in 2019, but rather than this resulting in fewer students receiving top grades, it resulted in more doing so - in line with Ofqual’s policy of a midpoint between 2021 and 2019 - because marks were higher.”

Further proof that exams were not ‘harder’ is evident in the data that shows despite requiring more marks to achieve a passing grade, the number of students taking exams and passing increased from 2019.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article