- Home

- Fighting the gender bias

Fighting the gender bias

As someone who has scuba-dived with sharks without a cage, I’ve rarely considered myself to be “not brave”. But not being brave enough is something I have heard a lot about recently in discussions about what could be holding back aspiring female leaders.

“What would you do if you weren’t afraid?” asks Sheryl Sandberg in her book Lean In: women, work and the will to lead, which explores why women occupy so few leadership roles.

Similarly, speaking in a TED talk, Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code, states that while “we’re raising our boys to be brave”, we teach girls to “avoid failure and risk”, curbing their ambition in the process.

There is certainly something preventing women from progressing to leadership in education. According to Department for Education figures, 74 per cent of teachers in secondary schools are women, but they comprise just 62 per cent of headteachers.

And in primary schools, although men make up only 15 per cent of the workforce, they hold 28 per cent of headteacher roles.

Not only that, but male headteachers earn more than their female peers in every sector of the state-funded school system. When you are facing these kinds of odds, it is no surprise that a healthy dose of courage is needed.

But is the problem really as simple as women not being brave enough? And if so, how should we go about fixing it? Sarah Barker, head of English and drama at St Bernadette Secondary School in Bristol, believes that bravery is definitely a quality that leaders need.

She says that the notion of bravery “has connotations of facing something that you’re not quite ready for or leaping into the unknown”, which could make it the perfect adjective, then, to describe the calculated risk of making a difficult strategic decision or of applying for a leadership role in the first place.

‘Be prepared to take risks’

Another female leader, who wishes to remain anonymous, likewise believes bravery to be an essential quality of leadership. As a school leader, you have to “know what you value and be prepared to take risks”, she explains. “You might have to go against what others expect in order to do what is right.”

So, bravery is a quality that leaders need. The question remains, though: is bravery something that women are lacking?

Interestingly, not a single leader I spoke to felt they had been brought up to be less brave because they were female.

In fact, many spoke of a very different experience, with strong role models permeating their childhood. “Perhaps in today’s society, girls are being raised to be even more brave than boys - ‘you can do anything and face anything’ - there are lots of strong role models and memes encouraging this,” says Shirsten Fry, a teacher of English from the Midlands.

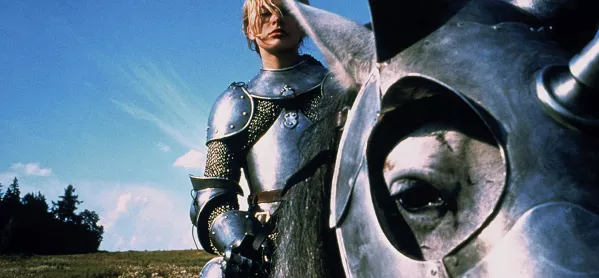

While bravery may historically have been connected to a kind of macho heroism, you don’t have to look far for examples that reveal this to be a complete fallacy.

Take, for instance, Malala Yousafzai, using her eloquence to fight the Taliban; the glamorous Katie Piper raising awareness for burns survivors; or the emotional intelligence of Brendan Cox in the wake of his MP wife Jo’s murder.

Such role models prove that being brave doesn’t mean acting like the stereotypical hero, who swoops in to save the day.

You can be brave while understanding your place as a jigsaw piece in a much larger puzzle. This is something that chimes with me as an assistant headteacher, who must be a team player within the senior leadership team as well as within the wider school community.

Being brave as a school leader equally doesn’t mean being fearless. In the right dose, anxiety can be a powerful motivator. Fear of failure can encourage us to work harder and achieve greater outcomes. In leadership, considering what can go wrong (and feeling worried about it) can actually make us more effective.

In fact, as a leader, I’ve arguably had to learn not to be braver but to be less so. I’ve had to learn to say “no” and to stay within my comfort zone to consolidate my professional learning and embed change.

For head of English Rebecca Foster, the idea that the lack of female leaders in education is down to an absence of self-confidence or caring too much about what others think is an over-simplification.

“I don’t think cowardice is holding women back,” she says. “I think it’s far more complex than that.”

Bravery isn’t the issue

I am inclined to agree with her. There is clearly a significant proportion of future female senior leaders for whom bravery isn’t really the issue. For them, it is not a case of considering what they would do if they weren’t “afraid”, but of creating the conditions within which more women can progress into leadership positions and stay there.

Are established school leaders brave enough to vocally challenge everyday sexism when they encounter it, no matter who the transgressor is? Are they brave enough to try different ways of working that allow men and women to balance and share outside commitments? Are they brave enough to promote women who might look, talk, and behave differently to leaders that have gone before them?

Perhaps it is not women who need to change, but the organisations within our education system that determine who makes it to the top.

Caroline Spalding is an assistant headteacher from Derby

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters