- Home

- The interactive whiteboard pioneer with a ‘killer idea’ to cut teacher workload

The interactive whiteboard pioneer with a ‘killer idea’ to cut teacher workload

When Tony Cann delivered a keynote address at the world’s biggest education technology show in January, he had a simple but striking message.

“We need new killer ideas,” he told the technologists and education leaders gathered at the Bett Show in east London’s Docklands.

Cann is the edtech pioneer who founded the global giant Promethean, where his work on interactive whiteboards has touched the lives of millions of teachers and pupils.

Edtech champion: Tes profiles Caroline Wright

Edtech strategy: DfE wants technology to cut time spent on marking

Edtech report: 'DfE investment needed for teachers to benefit from AI'

Now, Cann believes he has the killer idea that will do more than the interactive whiteboard ever achieved to transform education.

The problem he has been working on for the past 15 years is the lack of personalisation and real-time information in the classroom, and the solution he has come up with is a new app, Learning by Questions (LBQ).

Finally launched last October, it was hailed as the innovation of the year just three months later at the Bett Awards.

'There was no personalisation in my education'

With hindsight, the seeds of LBQ were planted decades ago.

Cann has little to say about his own education, which took place at Rugby School. “I was educated privately and it wasn’t very good,” he says simply.

When pressed, he adds: “There was no personalisation in it really, and this [LBQ] is an attempt to get personalisation into learning from a student’s point of view and a teacher’s point of view.”

Cann’s parents were refugees from Hitler's Nazi regime, coming to the UK from Austria and Czechoslovakia in the late 1930s. He was born months later, in 1939.

“They had a textile mill in Czechoslovakia,” he explains. “When Hitler came about they set up a mill in Blackburn to try to get some money out.

“They had to sell it eventually, but that brought them to the Blackburn area, and that’s really where I’ve been most of my life.”

It was in this industry that Cann gained another key insight that would one day feed into the creation of LBQ.

In the late 1960s, he was a manager of a large textiles mill in Lancashire, and realised that he needed real-time information about how the looms were performing. In 1971, he founded a company, Dextralog, to provide just this.

The firm harnessed Nasa technology – as well as importing the UK’s first mini-computer – to create a system that monitored 250 looms live. In time, it would be used in factories from Chile to South Africa.

“What we learned was that it was the presentation of the information that made the system – not collecting the information,” says Cann.

“You had to present it in a way that was useable by the people that needed it, and that’s exactly the same in classrooms today.”

'Whiteboards didn't achieve the improvement I hoped for'

Cann’s interest in education dates to 1990, when he became chairman of the East Lancashire Training and Enterprise Council.

It was a role that led to him being made a CBE for services to training, but also one in which he “saw how much there was to do in schools”.

“I have a crazy belief that we don’t nearly develop the potential of our young people.

“Loads of kids are turned out of school and basically they are not properly taught. Now, many are, but many are not, especially in the bottom third, and we need to do something about it.”

Around this time, he also gained an insight into the pressures on teachers when he was one of two industrialists appointed to a government committee on workload – he laughs ruefully at the fact it remains a burning issue today – and it prompted him to act.

“What appalled me was the amount of work teachers have to do outside of the classroom: preparation and marking.

“I think that is why I started Promethean because I realised that with some of the technology that we had at that time we could create a really useful interactive whiteboard, and that is what we did.

“In fact, we sold over a million of them over the next 10 years.”

For some, the mass rollout of interactive whiteboards in English schools in the 2000s is a salutary warning of the money that can be wasted on edtech, and when education secretary Damian Hinds wrote that, in the past, governments had been “guilty of imposing unwanted technology on schools”, he specifically cited “expensive interactive whiteboards”.

Cann himself believes that they have made a positive difference in schools, but equivocates when asked whether interactive whiteboards were value for money.

Without them, he says, there would be even fewer teachers because they have helped to cut workload. Cann also says they have opened up opportunities from around the world by allowing classrooms to link together. But he adds: “Value for money in terms of moving us forward much more than others? Not so.”

Cann acknowledges his own disappointments.

“Unfortunately, whiteboards did not achieve the improvement that I had hoped for. I think that they improved a bit, they made teachers’ lives easier, but I didn’t see an enormous improvement in the classroom that I knew was possible.

“It didn’t change the pedagogy. Teachers still taught at the front: I teach, you learn. There was no engagement, involvement, and what I did was begin to develop a system that would engage and involve and change the pedagogy.”

The app with 50,000 questions

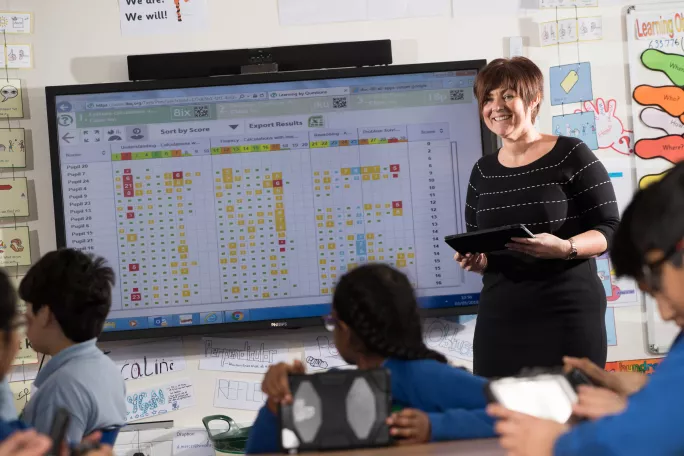

So what is LBQ? It is a classroom app that quizzes pupils on material that has been taught by their teacher. Using tablets, children progress through a series of questions. If they get the answer right, they move on to the next question. If they get it wrong, they receive feedback and try again.

Crucially, teachers can see in real time how their pupils are performing, allowing them to give immediate and personalised feedback to those who need it.

The system also allows for differentiation in the classroom with different groups of pupils able to work on different sets of questions.

For Cann, its benefits include the reduction of teacher workload by removing the need for time-consuming lesson preparation and marking, as well as pupils getting instant feedback to correct mistakes rather than having to wait days for written work to be marked and returned.

Predominantly catering for maths, science and English at key stages 2 and 3, LBQ currently has 50,000 questions written by a team of 22 people.

The concept behind LBQ is, Cann says, “absolutely obvious".

"But it’s been beyond the imagination, a bit like iPads were, if you like. Nobody thought it was really possible to do it properly, and nobody did it.”

What, then, are LBQ’s limitations?

Cann says it does not assemble the data for long-term analysis. Instead, “what we are concentrating on is better learning in the classroom for less-specific effort by the teachers".

"Teachers reckon they save an hour per lesson.”

He acknowledges that it is less well suited for subjects such as art, which “don’t have an easy answer”. LBQ can ask children to write answers out for such disciplines, and present them to teachers to look at, but cannot itself mark them.

When it launched last October, LBQ had 130,000 responses – answers to questions – per week. By the end of March, this was up to 1.1 million, and Cann is aiming for this figure to reach six million by Christmas 2019, and 128 million by December 2020.

He says that it costs schools £1 a week per child, including the equipment.

“We are a charity, by the way. We are not making personal money out of this,” adds Cann.

'£2.99 wine from Lidl is pretty good for me'

LBQ is funded by Bowland Charitable Trust, the Cann family charity.

Although a very rich man, Cann seems more grounded and humble than many other people who have made their fortune.

“They didn’t have a wife like I had, who was a superb non-materialist, and basically I think we had our feet reasonably on the ground,” he says.

“I get more fun through the things I do through the Bowland Trust than through anything else I can imagine.”

He has lived in the same house for 55 years, and describes himself as lucky not to have been bitten by the bug that sees others yearn for yachts and fast cars.

“Actually, I just get no fun out of large expenditures at all,” he says.

“I mean, I like a nice meal occasionally, but I can’t tell the difference between one wine and another, so why worry? A £2.99 [bottle] from Lidl is pretty good for me. If you put it in a decanter, no one else can tell the difference either.”

Instead, he has a moral mission: “I have to improve education. There are loads of kids out there who are not fulfilling their potential. What a waste.”

LBQ currently takes up about 90 per cent of the Bowland Trust’s spending, but it has also done work on prison reoffending, and supports Unitarianism and Cann's local church.

Cann also remains in touch with the day-to-day reality of state school life: he was the first chair of governors at Accrington Academy and still serves as a governor.

Why edtech will never replace teachers

In April, Damian Hinds – the first edtech enthusiastic to become education secretary for many years – unveiled the DfE’s long-awaited edtech strategy.

It is a plan that sets 10 challenges for edtech providers to address, and includes £10 million to help support the required innovations.

A few weeks earlier, Cann had used his speech at the Bett Show to say that the edtech industry “needs encouragement from government – it’s urgent”. So what does Cann make of the plan?

“I think it’s probably in the right direction, but relative to the whole of the education funding, it’s too small and too extended, too long.

“I have a sense of urgency. I see a child in front of me who isn’t achieving what they ought to achieve. I want that child to achieve and I think it will take too long to get there.

“But the general direction, we could approve of.”

And although Cann has made his fortune from technology, he is not someone who imagines that it will diminish the need for human teachers in the classroom in years to come.

He says they will always be required, “first of all to explain it, secondly to get the kids to stick at it, and then to deal with the interventions”.

And what of his thoughts on claims from edtech enthusiasts and sceptics who hope, or fear, that tech will spell the end for teachers?

He replies firmly: “That’s absolute bunkum.”

CV: Tony Cann

Education

- Rugby School; chemistry, University of Manchester

- Honorary doctorates from Lancaster University (1998), Edge Hill University (2012), University of York (2011)

Career

- 1960-c1968: Courtaulds, a textiles firm

- 1970: founder, Presspart

- 1971: founder, Dextralog

- 1977: founder, Terminal Display Systems

- 1990: chairman, East Lancashire Training and Enterprise Council

- 1990: member, Further Education Funding Council

- 1994: founder, TDS Circuits

- 1994: member, National Advisory Council of Education and Training Targets

- 1996: founder, Promethean

- 1998: board member, University for Industry

- 2007: founder, Learning Clip

- 2016: founder, Institute for Effective Education

- 2016: founder, Learning by Questions

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters