- Home

- Teenage behaviour: 5 tips for teachers

Teenage behaviour: 5 tips for teachers

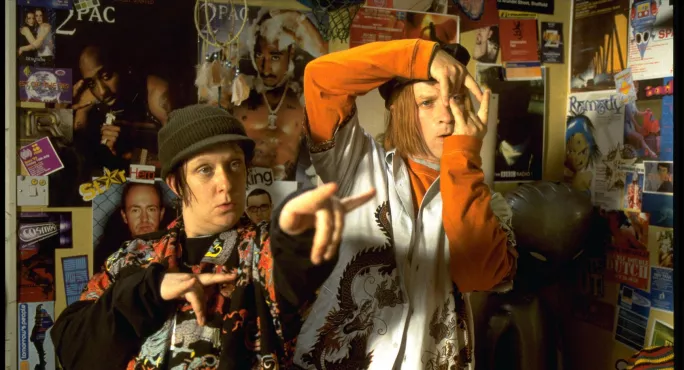

Why do teens behave in ways that are sometimes utterly confusing to their teachers? Researchers can give us some strong clues.

Studies have pinpointed adolescence as the period during which the human brain undertakes its final major construction project in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain through which the signals that underpin adult social behaviour flow. Blakemore and Mills (2014) sum up how this is expressed in behaviour:

-

Increased self-consciousness;

-

Reduced sensitivity to the feelings of others;

-

Increased concerns relating to peer evaluation;

-

Increased tendency towards risky behaviour in the pursuit of peer admiration, which at times may lead to embarrassingly socially inept mistakes.

-

All of the above come together to create increased social vulnerability

Quick read: The wait-and-see game over key stage 2 Sats results

Quick listen: Why there is no such thing as an unteachable child

From the magazine: Caped crusader’s mission to promote kindness in schools

The function of this period of development is to facilitate the learning that needs to take place to allow the individual to emerge into adulthood “equipped to navigate the social complexities of their community” (Blakemore and Mills 2014, p.189).

For example, both Blakemore and Mills (2014) and Wolf et al (2015) demonstrated through empirical research that the presence of a peer impacted far more heavily upon adolescents carrying out reasoning tasks than was the case for adults, illustrating the powerful impact of “audience effect” upon teenage behaviour.

Teenage behaviour: the teenage toddler

But what use is this information to teachers?

Most importantly, it helps them to understand the tumult erupting in the mind of a teenager, who may appear physically mature but may nevertheless frequently exhibit behaviour reminiscent of toddlers - including sulks and tantrums.

In situations like these, it is very tempting to respond with a “you are too old for this, get out of my sight” strategy.

However, comparative studies indicate that this might not be the best option. While human beings cannot ethically be experimentally deprived of social contact, studies looking at this with young rats have shown they are more likely to engage in addictive behaviour as a result, which later socialisation could not remedy.

Furthermore, while it is clearly unrealistic to let teenage tantrums disrupt a session for 29 other young people, the remedy of “the isolation booth” - particularly for children who are struggling with adverse experiences in other areas of their lives - is not effective either. Unless, that is, we are unconcerned about creating deeper problems that eventually impact the criminal justice system and mental health sector.

Safe spaces

Instead, we need to look to create situations in which teenagers have access to areas in which they can calm down and “rethink” a more developmentally informed strategy. It is also greatly enhanced when the area to which they are removed is staffed by pastoral adults who are trained to help them to more effectively organise their feelings.

The infuriating nature of the touchy, impetuous teenager can be managed towards positivity if such qualities are supported towards their more positive alter-egos, such as sensitivity and enthusiasm.

This can be facilitated by nurturing independence and self-reliance through the creation of enjoyable group challenges where success depends upon group members behaving in a responsible, inclusive and sociable manner. Guyer et al (2016, p.76) comment that adolescence is a period of both vulnerability and opportunity “hinged on the power of the effective systems to influence behaviour”.

Blakemore and Mills agree, proposing: “What is sometimes seen as the problem with adolescents - risk-taking, poor impulse control, self-consciousness - is actually reflective of brain changes that provide an excellent opportunity for education and social development’.

Five principles that underpin adolescence

So what are the five points for practice that teachers should consider?

-

Kelly (2001, p.30) commented that: “Youth is principally about becoming.” This is a useful point to remember when dealing with “awkward” teenage behaviour. While teenagers may look very adult in body, this is not synonymous with the events unfolding within the teenage mind.

-

Teenagers need to “play” with their own behaviour and its impacts upon other people. We would do well to more effectively consider ways that they might be able to do this in safe and supported environments.

-

The concept of “zero tolerance” has the potential to have a highly negative impact on children in the adolescent stage of development, in terms of banishing them from the all-important peer group. We need to work with children so that they find a nurturing environment in the places that they inhabit when their behaviour is not commensurate with remaining in a classroom. There also needs to be a clear goal of returning them to the peer group as quickly as possible.

-

We need to explore our current society to determine where young people might be finding positive reinforcement for poor behaviour in terms of increased peer approval both in school and out of school, and research societal solutions to eliminate such situations where possible.

-

We also need to consider whether assessments that impact significantly upon adult futures are really best scheduled at the height of adolescence. Now that children routinely remain in education until they are 18, do we really need high-stakes, summative assessments at 16?

To conclude, I don’t think I can do better than this quote from a teenage participant in a research project I undertook a few years ago: “Let us have fun and be stupid - we are teenagers.”

Dr Pam Jarvis is a reader in childhood, youth and education at Leeds Trinity University

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters