A series of books by Polity Press makes the case for the humanities. In History: Why it matters, Lynn Hunt makes a compelling case for her discipline, artfully avoiding the sterile debate between knowledge and skills. Academic history appears to have survived the relativist self-questioning that came with postmodernism: "truth" is back with a vengeance. The validity of facts and their interpretation might be debated, but history is back on track, setting the criteria for determining truth and relevance. A definitive test was passed when Richard J Evans took the stand (literally) in defence of history against holocaust denial. Hunt’s book takes aim at an updated range of targets – including those who fabricate fake news and "alternative facts".

The role of the historian as detective, as well as adjudicator of truth and relevance, foregrounds the skills associated with historical training: the search for and careful sifting of evidence; the judicious balancing of competing interpretations. But if skills were the only things that counted, it wouldn’t matter what is studied, the crucial thing would be how. Hunt’s case for history is not based on the acquisition of skills to the exclusion of knowledge; rather, it rests on the way these combine to provide historical perspective.

Hunt’s book shows how, in recent decades, perspectives have become more inclusive with respect to class, race and gender. History still serves a citizenship function, binding us in a national narrative; but our shared story has become richer and more diverse. It is readier to engage with victims as well as victors.

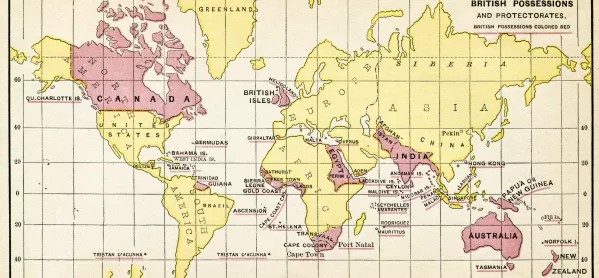

Historical education in England is also increasingly accommodating a trans-national perspective, but it needs to go further. A full understanding of British identity and its formation requires that students engage with our contested place in the world – including the contingent nature of "Western" dominance. It is increasingly appreciated that at the dawn of Europe’s expansion overseas, there were societies and civilisations that were more advanced than we were. Still, Europe prevailed, and history still rewards the victors.

A new study of the origins of Western dominance deserves to be read by those designing school history courses. In it, J C Sharman argues that the era of dominance by Europe and its offshoots began much later than historians have allowed. For centuries after Vasco da Gama, Europeans’ grip over their growing overseas empires remained tenuous, merely tolerated by the existing land-based powers. World history courses don’t dwell on the fact that the East India Company pledged allegiance to the Mughal emperor. Students learn about "our" military victories such as Plassey, but hear less about the many serious defeats for colonising powers at the hands of Asian armies. Sharman observes that before 1700, more of Europe was under Asian rule (courtesy of the Ottomans) than the other way around.

The West’s hegemony was not secured until well into the 19th century, and may well already be over. Such a perspective encourages humility, not hubris, and constitutes a basis on which to develop a nuanced understanding of our place in the world today. Today’s young people will face the challenge of redefining our relationship with the rest of the world, and understanding how we got here is a crucial part of that.

Historical education shouldn’t just be an "entitlement", it should be an imperative. Yet, beyond key stage 3, history is deemed discretionary and therefore dispensable. Given what is at stake in recalibrating Britain’s role in the world, a policy of national amnesia seems rather reckless.

Kevin Stannard is director of innovation and learning at the Girls' Day School Trust. He tweets @KevinStannard