The ‘nerds who don’t do words’ need reining in

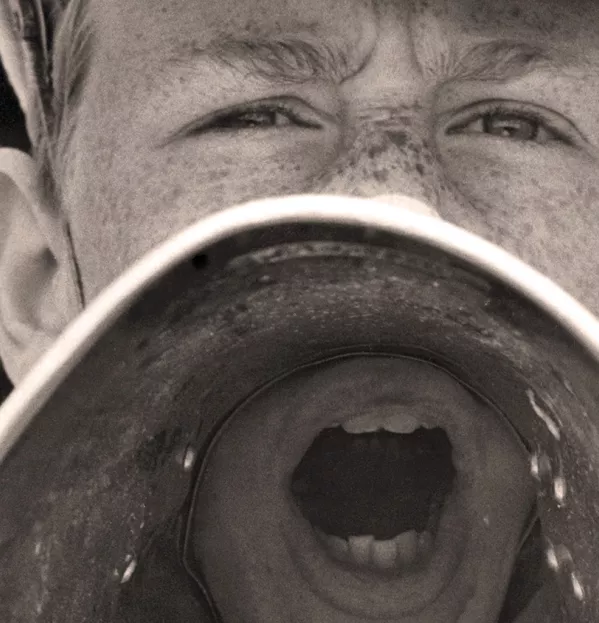

If you’ve been reassured to find educational technology being increasingly challenged and criticised, I have bad news for you. Lobbyists and advocates for the industry have their fingers firmly thrust in their ears. They’re not listening to teachers’ views.

In fact, they’re reaching for the megaphone. One company with international ambitions, EdTechXGlobal, in a forecast released earlier this year, argued that educational technology was “a global phenomenon” and projected world-market growth at 17 per cent per annum, to reach spending of $252 billion (£205bn) by 2020. That, of course, is $252bn that would not be spent on those pesky, inconveniently fleshy costs called teachers.

While estimating the global education market at more than $5 trillion (£4.07tn) - that’s eight times the size of the software market and triple the size of the media and entertainment industry - these lobbyists complain that education “is still only 2 per cent digitised”. So expect a lot more energy to be expended convincing people who write the cheques that new technology is an essential aspect of every teacher’s job.

The interesting but short-lived attempt by education publisher Pearson to follow the model of the pharmaceutical industry, so that product-development teams were tasked with placing efficacy at the heart of their work, has prompted me to reflect on where the “ed-tech revolution” now stands internationally.

Drug companies are actually a fascinating benchmark for the educational technology industry. They have learned the hard way in recent years that, however intangible, a company’s reputation is among its most valuable assets. Global and minor drug companies alike have been hit by national and international scandals that have rocked public confidence in the industry. A survey by PatientView in 2013 found that only 34 per cent of patient groups believed multinational drug companies had a good or excellent reputation (80 per cent of respondents being European). People increasingly feel that, as far as these companies are concerned, the needs of patients are secondary.

Just imagine a large-scale, trustworthy survey of teachers globally that captured their views on ed tech. It would make invaluable reading for all those with their fingers in their ears, if they were in any way inclined to read about it, but one of the problems is they are not. Far easier to bleat the soundbite or marketing message than to wade through all that unnecessary text and work out what the real world is thinking.

When IT is your business, an appealing graph or selective statistic is far easier to understand than all those troublesome words. Which is particularly frustrating if, like so many teachers, you spend time and energy trying to teach children how important it is to be able to read - whether it is a tabloid newspaper or a thesis - before they enter the world of work.

Digital dystopia

We’ll be damping down the current technology firestorm for decades to come - largely because nerds who didn’t do words ignited it. Far too many people are working at what’s on their computer monitors instead of the problems they conceal. Edward Snowden’s bookshelf may have been thin on personal ethics, but I suspect it held a dystopian novel or two besides all those three-inch-wide reference manuals on SQL and Java.

There isn’t enough space here to detail the bewildering sums of money spent on the countless and pointless ed-tech products, or projects that have found their way into vulnerable classrooms and schools worldwide without anyone seriously making the kind of effort required to justify the cheques being signed. If you doubt me, read what the World Bank’s InfoDev team have to say about this. Suffice to say that ICT remains the second-highest item on school budgets by far, after staff salaries.

Before any more teachers’ jobs are made more onerous, not less, by someone who isn’t a teacher telling them they should be using something shiny and new for no other reason than that they have convinced the cheque signatory, I think schools and teachers should be demanding a change in the way the industry does business with them. So vast are the sums, so high the costs to children and schools in wasted time and effort, that what we need before a new wave of zealots launches a fresh assault is an ethical framework for any organisation wishing to sell technology into schools.

I would like to see teacher organisations come together with government to work out a clear and positive framework, spelling out what schools, teachers and children have a right to expect from any ed-tech business, global or local. No one in the lengthy food chain these businesses rely on should settle for anything that is not completely focused on enabling credible educational change, instead of merely delivering technology.

We no longer tolerate teachers who can’t teach - so why tolerate technology that doesn’t have an impact? Ed-tech brassnecks need winding in.

Until such a framework started to take shape, here’s some pragmatic advice for all potential cheque signers: ask the supplier to show you the risk register they are running, aligned to the product or service they wish to sell you (that is, if they can find one). Insist that these three risks are included: impact on the quality of teaching; impact on pupils’ learning; and impact on school culture. Better still, get the professional educators you intend to be the end users to define these risks for the supplier and demand that what they say goes in the risk register. That would be a far more valuable contribution to our wider culture and society than any cheque that you hastily scribble your name on. And you won’t even have to seek asylum in Moscow.

Joe Nutt is an educational consultant and author

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters