The school rising like a phoenix from the ashes

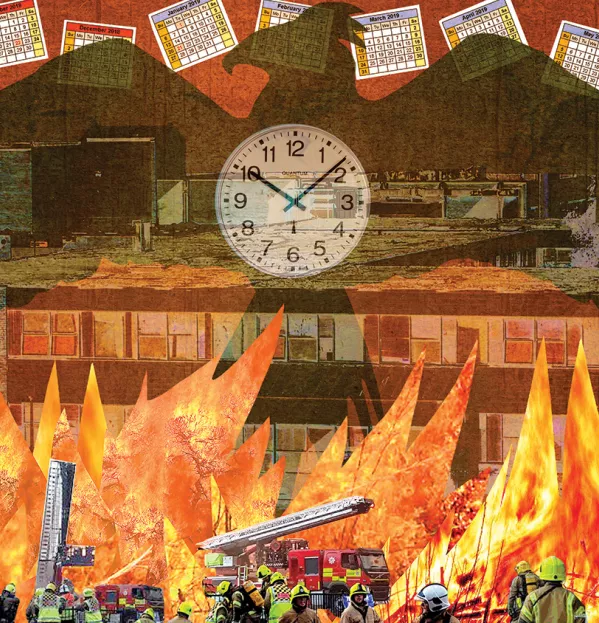

At 10.05pm on Tuesday 11 September, Lesley Elder got the sort of phone call that no headteacher ever wants to receive. The head of Braeview Academy in Dundee had just changed into her pyjamas, and, after a long day including an induction event with other recently appointed school leaders, was ready to zone out in bed with some Nordic noir on Netflix.

But then the phone rang: it was the city council’s head of education, Audrey May. The two of them knew each other well, but they didn’t make a habit of chinwagging late on a school night. Something was up.

May, herself a former secondary head, got straight to it: “I don’t know if you’ve heard, but the school’s on fire.”

Elder’s disbelief was quickly replaced by the urge to spring into action. “I’ll see you there at the top of the brae,” May told her, using an informal name for the school, which sits atop a small hill that dominates the local geography. Elder threw on jeans and a top and drove the 20 minutes to the school. Her arrival has already become part of Braeview lore, with apocryphal details adding extra spice to the drama.

‘Is this really happening?’

“The legend is that I turned up in a pair of fluffy Elmo pyjamas and I was on my knees praying to God to stop the fire,” Elder says, with a smile. But no one was smiling that night. She found about 40 people - pupils, parents, staff - gathered at the foot of the brae, “wandering around in shock, saying, ‘Is this really happening to us?’ ”

“The whole of the sky was lit orange,” recalls Elder with a shudder. “We were all aghast. It was like the whole roof had gone on fire. This strong, acrid, heavy smell was hanging in the air. There was belching smoke - that was bad enough.”

There was also a “raging wind” and Elder feared that at least half the school - Braeview’s boxy 1970s premises is split into three parts - was done for, maybe even all of it.

But, right then, her thoughts were already turning to what would happen the next day. Braeview, on the northern edge of Dundee and overlooking farmers’ fields to the back, is the hub of a community where around a third of pupils are eligible to claim free school meals.

“I was in shock, but still planning - my mind was going crazy, trying to think, ‘OK, then, what do we do now?’” she recalls. Elder was one of the few people allowed inside the police perimeter to reach the top of the brae. Since managing the fire was out of their control, she, May and Paul Clancy, executive director of the city’s children and families service, were already throwing around ideas for what would happen in about 10 hours’ time - when, under ordinary circumstances, pupils would be arriving at school.

May says: “We were all absolutely stunned, shocked and devastated, as it looked as if the whole school was covered in flames. But even as we stood there, we started to plan what we would need to do to minimise the disruption to our young people’s education.”

Their worst fears were not realised. The resulting damage was bad, but it could have been much worse. The kitchen area next to the canteen was the only part of the site that was completely gutted: staff returned to the school on Thursday of last week, with all pupils back at the start of this week, although the worst-affected half is still out of bounds, including the spaces for English, maths, social subjects, support for learning, IT and business, and a fitness suite and gym. In the meantime, an adjoining temporary accommodation “village” is springing up to take their place.

On the night of the fire, Elder finally left the school shortly after 1am, and barely slept. She fretted about not only how the school’s 570 pupils would be taught but also where the many who relied on its breakfast club would get something to eat.

A meeting was set up for first thing the next morning, with senior council staff and the heads of two other schools - Craigie High and Baldragon Academy - that might be able to accommodate Braeview pupils. Within an hour, recalls May, timetabling plans were taking shape; the “amazingly resilient and positive” Braeview staff “immediately started planning home visits and calls to check in with the most vulnerable pupils” - the “sense of community spirit” was “incredible”.

A week later, S3-6 pupils were having their lessons at Craigie; five days after that, S1-2 pupils started at Baldragon. It was 13 days since the night of the fire, and everyone was back inside a school.

In November, I accompanied Elder as she returned to the school where she had been head for just over a year.

Instead of the usual lunchtime hustle and bustle, I find the building surrounded by a squadron of yellow-and-black-striped security sensors on tripods, like a pincer movement of inscrutable Doctor Who villains. Doors and windows at the entrance are covered in sheets of metal resembling giant cheese graters, like those thrown over empty homes in dilapidated housing schemes.

Inside, desiccated leaves are strewn across the foyer. By the entrance, a peach-coloured plastic hair curler is a remnant from the school’s abandoned cosmetology suite. Chipboard panels rest against corridor walls and coloured wires dangle from above. It’s like the opening scene from a post-apocalyptic zombie film, except for the pallet of new IT equipment reminding us that the forlorn look of the place is only temporary.

If the school feels eerily still for me, what must it be like for the head who dedicates her life to the place?

“I just want it back,” she says, surveying the damage and incipient decay in a central garden area beyond the foyer. Weeds are surging through the gaps between paving stones and an apple tree has shed a pile of fruit that would be large enough for home economics pupils to make dozens of crumbles.

The fire - which led to charges being brought against a 15-year-old boy - rampaged along the roof but did not penetrate as much of the building as was at first feared. You can see the stain of black drips and the buckling of metal bands between the roof and the exterior walls, evidence of the building’s rearguard action. Although it is too early to determine the long-term ramifications, the fact that every area looks potentially repairable is a “miracle”, says Elder.

Much of the damage was actually caused by water. Firefighters siphoned off the school’s swimming pool, and the legacy of the elemental battle that ensued hits you when you push through the double doors into the dining hall. Anyone who has walked through an Islay whisky distillery will know that the smell is remarkable: similarly, at Braeview, the pools of water in the school dining hall and the lingering odour of smoke give the effect of inhaling the fumes of a peaty malt. A Laphroaig, perhaps? The water did a lot of damage to the music department - several electric keyboards standing in one corridor were among those instruments that could be salvaged - and fungus and mildew are creeping around the building.

Pupils still gather at the foot of the brae each morning to be bussed to Craigie (about 2.5 miles away) and Baldragon (4 miles), accompanied by whichever staff are teaching them in the first period. Those journeys eat into the school day, and there have been some concerns from senior pupils and their families about the impact on exam results, picked up on in local media reports.

But Braeview staff have been “falling over themselves” to help pupils to make up for any missed study in whatever way they can, says acting depute head Kenny Clarkson.

One significant decision was to arrange study sessions during the two-week October holiday - these usually run only at Easter - and teachers have also worked with groups of pupils at lunchtime and after school to keep them on track. The school has shaved a few minutes off some classes to create more time for exam subjects as a temporary solution, while the Scottish Qualifications Authority will permit some pieces of coursework to be submitted later.

Meanwhile, the S1 transition process has effectively had to be repeated for more unsettled pupils, including autistic children. They had only had a few weeks to get used to one big school, and all the upset that can cause, before the fire necessitated the move to another.

Resilience and ingenuity

Dave Souter, the school’s principal guidance teacher, says that work on “growth mindsets” over the past couple of years has helped to build the resilience that will support the school through this testing time. There has certainly been some ingenious improvisation from staff in the face of adversity. A music teacher, for example, went to a garden centre and bought a bunch of wooden canes that you might use to grow runner beans, sawed them into smaller segments and redeployed them as drumsticks.

Other schools have rallied round: Elder says every other secondary in the city has donated materials to Braeview, as has the broader community. Dundee United Football Club, for example, arranged activities for pupils with additional support needs, while Dundee and Angus College has taken in Braeview computing students. Tyre manufacturer Michelin - whose Dundee employees have had their own well-publicised problems with the announcement of a potential factory closure - provided the school with scientific calculators, as well as boiler suits and boots for pupils studying mechanics.

A “phenomenal” amount of online learning resources were uploaded in the week after the fire, so that pupils could keep working while away from school, says Elder. As a result, Braeview staff - who communicate between Craigie and Baldragon using walkie-talkies - have become more “IT savvy”: unlike before, almost every department now uses Twitter to share homework. “We were maybe a little bit behind the times, but this situation has given us a push,” she explains.

A small number of parents have complained about the time taken getting pupils back to Braeview, but Elder says that, once the details of the complex process is explained, they are more understanding. The building still has to be deep-cleaned, and who knew that a school swimming pool could be heated up by only one degree a day?

The operation to put up 30 temporary buildings has been underway for about five weeks when I visit. The school has been involved in discussions about myriad related issues - emergency access, lighting, tarmac, drainage, electricity, whether the site could support the weight of the structures - which Elder says provided “an education in project planning”.

“I’m amazed, gobsmacked, that it’s progressed so quickly,” remarks Elder, as she catches sight of the high-spec temporary buildings - including bathrooms and, in theory, better wi-fi than the school is used to. They are a far cry from the draughty, oversized shoeboxes many people will remember from their youth.

The imminent return to Braeview - “back home”, as Elder puts it - will be tinged with sadness, as sharing premises with two other schools has sparked a spirit of collaboration between teachers who, but for the fire, might never even have met each other.

Baldragon has gifted a trophy to Braeview, which will be awarded annually to a pupil who excels in some form of partnership working.

Souter, who has worked at Braeview since 2000, is remarkably upbeat, given what the school has gone through. “I have great faith in the Braeview community,” she says. “We’re tight-knit as a staff, we’ve got great relationships with young people, and I don’t think that will change in any way - if anything, it’ll be strengthened. If there’s one school that can cope with this situation, it’s us.”

Some Braeview staff do not have the same well of experience to draw on as their more experienced colleagues. Elder thinks that they, in particular, will remember the aftermath of the fire as a critical point in their careers: “I’ve been saying to some of our newly qualified teachers, ‘If you can deal with this, you can deal with anything.’ ”

Henry Hepburn is news editor for Tes Scotland. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

Edinburgh closures had ‘limited’ impact on attainment

In January 2016, a gable wall at Oxgangs Primary School in Edinburgh collapsed during Storm Gertrude. The incident led to 17 school buildings in the city being closed temporarily for safety reasons, some for several months.

A subsequent wide-ranging review by architect Professor John Cole, however, found few signs that senior secondary pupils’ attainment had been affected.

He wrote: “It is difficult to determine and it will subsequently be difficult to prove whether the closure and decant of the schools has had any longer-term negative impact on the educational attainment of the pupils affected.”

He added: “However, on the basis of the evidence provided … any negative impact is likely to have been of a limited nature and that these may have been offset in certain instances by some unexpected positive impacts of the experience.”

‘You have to come together’

S6 pupil Hannah Gillespie says that the past few months have been “tough” as a result of the fire. As if school wasn’t stressful enough - with critical exams on the horizon - she was worried about suddenly being sent to Craigie High, a place she had never set foot in before.

“But it’s actually not been hard at all - it’s just like we’ve had to get on a bus to get to the same place we usually go to,” she adds.

Fellow S6 pupil Samuel Reid-Harper says: “The main worry right now is exams. Everyone’s thinking we’ve been set back quite a bit here, we’re going to have to work extra hard to get through this.”

But he has found supplementary study sessions organised by the school have helped to make up the time taken travelling to Craigie, and pupils and staff are now closer than they have ever been.

“If you go through something like this with people, you’re automatically going to sort of bunch up, even with people who wouldn’t have really spoken to each other before,” he adds. “You’re in a situation where you have to come together to get through it.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters