Why handwriting matters more than ever

How good is the handwriting of your pupils? For the most part, it should be legible, at least. Few schools have embraced the digital world to the degree that everything arrives to be marked or read having been typed on a computer. And exams remain persistently analogue - the pen still rules.

But being able to read a young person’s writing is not the only condition that should be considered by teachers. Speed, the level of clarity, how much of a barrier the writing of words is to the thinking of the words, how much pain, even, handwriting causes - these all matter not just for learning, but for how far a child can demonstrate learning.

So how well are we doing on these aspects? Unfortunately, the signs are not good. According to a 2016 survey by the Write Your Future campaign, more than a quarter of primary school children are unable to join up their writing and 19 per cent can’t write in a straight line. Meanwhile, in a news report last year, Dr Sally Payne, head paediatric occupational therapist at the Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, said that children are going to school without the dexterity needed to hold pens and pencils correctly. And teachers frequently complain of a lack of stamina among pupils, and express fears about how far examiners will be able to read the papers of even 16-year-olds.

Might of hand

Dr Mellissa Prunty, a paediatric occupational therapist at Brunel University London, studies handwriting in schools. That it is still an essential skill, she says, is indisputable.

“It is still the main medium for writing across the curricula, from the early years foundation stage through to A levels,” she says. “Handwriting is still fundamental and that isn’t going to change any time soon, despite technology.”

She argues that handwriting should continue to fight off the challenge of technology, because it is far more effective as a tool for learning than typing.

“You start generating ideas, then you put them into language,” she explains. “You then need to construct your sentence by using the rules of grammar, followed by thinking about how to spell the words. You have to map the sound of each letter to the visual representation. You then retrieve the movement patterns linked to the sound, which results in a set of instructions being sent from the brain to the muscles, which results in the movement of the pen.

“The difference with typing is that you don’t have the same level of processing, particularly around the mapping between sounds and patterns of movement. Instead of producing patterns, you press a key.”

In her research, she has developed, along with colleagues, the Handwriting Legibility Scale, which can be used in the classroom for assessing the script of children aged eight years old and above. She has also looked at handwriting difficulties in children with and without motor impairment, and those with dyslexia. Handwriting difficulties, she says, have a big impact on learning.

“For children with developmental disorders, their handwriting is impacted either by a movement, spelling or language impairment,” she says. “We know that they write less and because of this, the quality of their writing is below that of their peers.

“So if you’re sitting a geography exam or writing an essay, the quality of your message is likely to be impacted, because the cognitive resources usually available for focusing on the message are being spent on the language, spelling or the handwriting itself.”

Joined-up thinking

How do we begin to help pupils handwrite better? Prunty points to a 2017 Ofsted report that found that 83 per cent of school leaders believe that newly qualified teachers aren’t well trained in spelling and handwriting. As such, she feels that proper training is crucial.

“At Brunel, we work closely with the education department to give teacher trainees a session on handwriting,” she explains. “Not all universities do that, so we often have newly qualified teachers arriving to a classroom of 30 children and expected to teach handwriting. Many of them learn on the job,” she says.

She says a wealth of information can be found in the Developing Early Writing document issued by the Department for Education in 2001.

“It was circulated to schools as part of the Literacy Hour and was detailed in telling teachers when, what and how to teach in terms of handwriting,” says Prunty. “Going back to that would be a good starting point and you can still download the document from the National Archives website.”

She also urges more consideration of when fully joined-up writing is required.

“Sometimes you’ll see children in Year 1 start off with continuous cursive - that is, fully joined handwriting - which is tremendously difficult because you essentially double the amount of strokes required,” she says. “[And] you have to control the pen while it’s pressed on the page, which is quite dexterous.

“Whereas if you lift the pen, which most of us do naturally when writing, the pen will roll in your hand and it’s less difficult to manipulate it compared to when it’s fixed on the page.”

In general, Prunty advocates a mix of joined and unjoined writing.

“We know from research that this style of handwriting is quicker and more efficient. Joining is a contentious issue and there’s a real disconnect in the guidance. For instance, if you look at the teacher assessment frameworks for key stage 2, it states that children need to join their handwriting to work at the expected standard for English.

“But look at the Year 6 curriculum and it says that children need to know what letters are best left unjoined.

“So the curriculum is saying we’re not talking about fully joined handwriting, but the teacher assessment is saying we potentially are, and teachers don’t have any guidance on what letters should be left unjoined.”

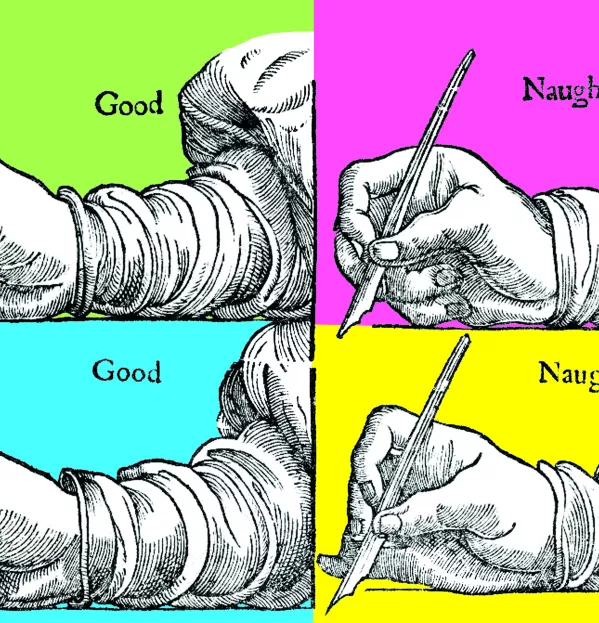

The issue of grip is another topic of controversy and Prunty has concerns about the early years foundation stage Profile pilot, which states that children should develop the “dynamic tripod” grip - essentially, making a tripod with the thumb, index and middle fingers with the pen in the centre.

“If approved, this will name the tripod grip as the standard that children must achieve at the end of EYFS. To me, this is problematic as we know from research that there are many ways to hold a pen and this particular decision seems contrary to the evidence,” she says.

Where more care should actually be taken is with how children get their letters down on the page, Prunty adds.

“Letter formation is something that doesn’t get enough attention,” she says. “In the clinic - even with children who don’t have any cognitive or movement difficulties - we see that children will perform the letters in a way that would never be taught. For example, with the letter ‘d’, they might draw a circle first and then go back and add the line. It looks like a ‘d’ but if you’re trying to build speed and move fluently across the page, that is going to be difficult when the child gets older.”

Most of all, though, Prunty says that what would make the biggest difference is giving children enough practice. She recalls a study presented at a writing conference she attended a few years ago in which a PhD student visited Year 5 classes in five different schools and photographed everything the children had written over a week.

“The researcher counted all of the words and looked at the quality of the vocabulary,” she explains. “She found that one school had written an average of 250 words per pupil in the week, while another had produced 1,600 words per pupil in the week. The school producing more words was producing better-quality writing, using low-frequency words as vocabulary and were better on spelling.

If we are going to get handwriting right - and subsequently learning right - more is, she says, usually better.

Christina Quaine is a freelance writer Watch handwriting tutorial videos by Tes columnist Nancy Gedge here: bit.ly/GedgeWriting

This article originally appeared in the 26 April 2019 issue under the headline “Tes focus on… Handwriting”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters