How learning to drive made me a better teacher

Helping a student who struggles can bring elation and despair, hope and hopelessness in equal measure. And our belief in our students is frequently met by their total lack of self-belief.

I have a student who thinks she’s failing. Teaching her is draining because, whatever I say or do, it seems as though she believes all progress to be impossible. Every time she is faced with a task that is outside her comfort zone - and it seems that is most tasks - her instant reaction is to exclaim, loudly, that she can’t do it. When given something to read, she says she can’t read. When given something to write, she says she can’t write. She folds her arms; she looks upset; she messes about; she tries to copy from other students.

Yet she is sparky, with an acerbic humour, which tells me she can think intelligently. I really believe in her: I know she could do better, if only I could help her with the steps along the way.

But the last thing she seems to want is my belief in her. In fact, if anything, my encouragement seems to make her feel worse.

All of this puts me in mind of another pupil - someone who recently learned to drive. Colin, an experienced driving instructor, took on a student who had already failed two tests, each time with three major faults. She had not driven for nigh on two years, since the day of her last failure, and this was a last-ditch attempt. Unlike my student, she had enough confidence to give this one more go - this time in an automatic - as an intensive course of lessons over two weeks, with a looming deadline of a test at the end of it.

Colin knew, as I knew with my student, the possible challenges that were in store. Just as we have special educational needs and disability information for those in our classes, this student had let on that she was dyslexic and dyspraxic. Colin was chosen specifically for this reason: he, too, was dyslexic. He would, she was sure, understand her frustrations and difficulties, not as facts about her, but from the inside.

So often, we understand that students are having difficulties, but we do not understand their difficulties themselves. When I struggled with bearings in GCSE maths, my teacher knew I didn’t get it, but he could not seem to understand why. My struggle was solitary. This is commonly the case with education: you usually teach something you’re good at. Colin’s student had sought him out not primarily because of his capacity to drive (which she took as read), but for a capacity to teach that came from a place of empathy.

Her previous teachers couldn’t do this. One had been driving tractors since the age of 12. Driving came as second nature to him. It was obvious. “Just park it!” he’d say, with no explanation of how. She’d give it a go. She’d end up straddling the line. She’d try again, and fail and fail. He’d say “Go on. It’s easy!” He could not understand why she never got better.

Perhaps this explains why showing my belief in my student seems to put her off rather than encourage her. When she says “I can’t do it” and I say “Of course you can. It’s easier than you think,” am I being as encouraging as I think I am? I am directly contradicting her. She says she can’t do this, and I say she can. I’m right to contradict her belief but, in doing so, I need to remember not to be dismissive of the feelings she has. I must not contradict or downplay the feeling of helplessness out of which her statement is arising. She is not right that she can’t do it, but she is right that it feels that way.

Colin’s student frequently felt the same. This was the only thing she had ever properly failed. She was generally pretty high achieving. She’d never struggled at school and was pretty academic. She’d done music exams. She was bad at sport (presumably because of the dyspraxia), but didn’t have to play team sport any more, so it didn’t matter to her.

When driving, she often reported that she had no clue what to do and had not the faintest idea how to begin. She felt as though there were big gaps in her brain, through which neural paths were failing to connect. When met with a problem, her brain would come back with a lacuna of silence in place of a solution. Imagine her frustration: trying and trying and feeling as though the basic tools to do the job are missing.

My student’s eyes double in size at the sight of most tasks. She physically recoils from written instructions, and now I see why. She looks at them and has no idea where to begin. Colin’s student felt like this at roundabouts; my student feels it when she approaches written work.

Colin never showed blithe, empty “Of course you can do it” belief in his student. He was calm, he was patient and he kept her going, on and on, on and on, until she made progress. And he recognised her difficulties. He never said it was easy just because he found it easy, but recognised that it was hard because she found it so.

And, slowly but surely, his student improved a little and became a little more confident, and improved a little more, and became a little more confident. On the day of the test, he went with her, neither of them assuming a pass was on the cards. But this gentle building of confidence had worked: she passed.

Avoiding hazards en route

If you haven’t guessed already, Colin’s student, dear reader, was me. I finally passed my driving test in an automatic, in the Easter holidays, aged 34. I have to say that learning to drive has been the best CPD of my career. It has given me so many new insights - into teaching, yes, but also, importantly, into vulnerable learners in a position of weakness.

We should not underestimate how difficult it is to keep going when you’re failing. When it was happening to me, I sometimes wanted to scream, shout, swear and cry, all at the same time. The frustration was horrible. And I was lucky, in that this was a particular area of weakness; some students feel that way much of the time. I don’t blame them for disengaging. Not caring is better than having to endure that feeling. In fact, I am stunned by the excellent behaviour people in that situation so often muster.

What made Colin’s teaching work for me was that he never contradicted me. He never said something was easy when I was finding it impossible. I’ll never forget what he said one day, as I screwed up a roundabout: “You’re really finding this hard, aren’t you, Clare?” In that one sentence of understanding, so much ground was made with my learning.

Just as previous teachers had told me that parking, roundabouts, one-way systems and slip roads were all easy, and that I could manage them, I too am guilty of telling pupils they can manage something they find impossible. In my own version of the instructor who had been driving tractors since he was 12, I have been into philosophy from a pretty early age. It was as natural for me to become a religious studies and philosophy teacher as it was for him (presumably) to become a driving instructor.

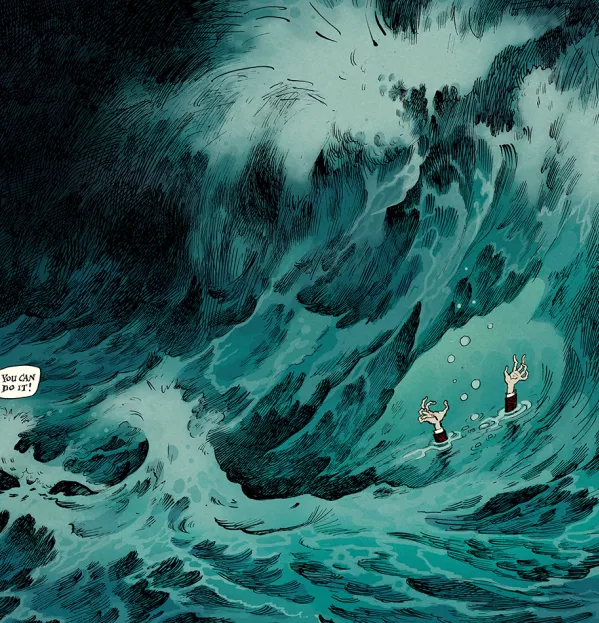

I have vowed to myself (though I have already broken my vow a number of times) never to tell someone that something is easy if they seem truly to be saying to me it is difficult. It seems like kindness to show belief in the struggling student but, without empathy for their situation, it can actually be very cruel. It’s a bit like standing on an island while they’re drowning in the sea, and asking them why they’re all wet. It is, after all, really easy to be dry. We must listen to the student who says they can’t do something. They may be wrong, but the fact that they believe it to be true deserves recognition and engagement.

Colin - his real name, by the way - will never know the full effect of his teaching on my confidence, on my understanding of my disabilities, on my coming to have more of a growth mindset about driving and other areas of prior weakness. But my students will, I hope, feel the benefits of the lessons he taught me.

I’m not a learner driver any more, but I’m more of a learner than ever. And, for that, I will be for ever in Colin’s debt.

Clare Jarmy is head of academic enrichment and Oxbridge, and head of religious studies and philosophy, at Bedales School in Hampshire

This article originally appeared in the 17 January 2020 issue under the headline “When a student feels boxed in, try a parallel manoeuvre”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters