Pull up a beanbag: it’s time to learn

Imagine trying to write a thesis while hunched on an intercity bus as the man beside you chomps through a foul-smelling cheese and onion sandwich, and another passenger’s headphones assail you with thunking basslines. Or imagine asking the chief executive of a FTSE 100 company to craft an annual report during a heatwave in a windowless box room without any air conditioning. Or expecting a surgeon to perform a life-saving operation as colleagues squabble over who stole whose parking space that morning.

Peace. Comfort. Space. Light. Clean air. These are not luxuries but essentials for doing our jobs well. Presented with working conditions that lack these basics, adults will complain that they cannot be expected to perform at their optimum level.

Yet, countless schoolchildren are expected to turn up each day to buildings designed during a time when the principles of education were radically different to those holding sway in 2018: speak when spoken to; don’t ask questions; accept your (ritualistic and humiliating) punishment. The buildings - dark and austere, cramped and linear - are often a reflection of these discredited values. And this is not merely anecdotal: about 15 per cent of Scottish state school buildings are “poor”, despite improvements in recent years (see figures, page 18).

Inadequate school buildings continue to provide the daily learning environment for many thousands of pupils around the country. Until this summer, one school that fell far short was St John’s RC Primary in Edinburgh. “I couldn’t see out of the window because I was too small,” says P3 teacher Lyn Williamson - who, to be clear, is not particularly short. Day after day, staff and pupils worked away as shafts of sunlight extended tantalisingly above their heads and glimpses of the outside world were denied by the building’s joyless design.

This wasn’t the only frustration. Spending time in the senior-leadership room was less than tempting since, as veterans of the old building will tell you, “it was where the mice came to die”.

And if a pupil needed some extra help, they often found themselves being educated in a cupboard. It was a cruel message echoing down the decades from those who signed off on the building in 1929 - implicitly telling children that they were at the bottom of an educational pecking order, regardless of the care and support that modern-day staff were showing them.

‘Space was a challenge’

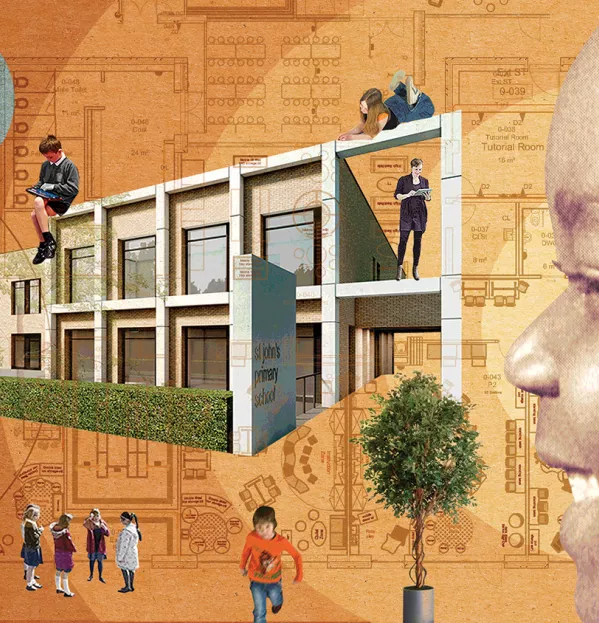

St John’s, which opened its new premises in August, was the first primary in Edinburgh to be built under the Scottish government’s Schools for the Future programme. It was officially opened by education secretary John Swinney in October. At the ceremony, recently retired headteacher Barbara Service - whose relationship with the old building started as a pupil 55 years ago - had this to say: “Space was an enormous challenge …but now there is the opportunity for more flexibility for teaching and learning, meaning far better opportunities for the pupils to learn in cooperative and innovative ways.”

The new headteacher, Jackie Kelly, describes a “seismic shift” since the school moved. So what’s changed? The first thing most teachers mention is the light that cascades through the building, spilling through the extraordinarily long corridor that acts as the central artery of the school - it instantly makes people feel better, says Kelly.

There is a literal bounce in the step of staff, such as P1 teacher Ann Robinson. She worked for 25 years in the old school and says the new building “gives you more of a buzz”. Robinson is overseeing an array of learning activities when I visit, with pupils breaking into little groups for all sorts of explorations around a class topic on the planets - some are sculpting Play-Doh, others are playing a board game, still others are musing over a mind map. One boy comes up, scarcely able to contain himself and wait for his teacher’s attention, as his politeness battles with his urge to share an idea he’s just had.

Robinson says the children are calmer and more focused than before thanks to the new building, and that their natural curiosity flows more easily. She recalls the depressing amount of time - a good 15 minutes - it used to take pupils to settle down at the start of the day in the old, cramped surroundings.

Kelly says that “the opportunity for flexible learning has been incredible”. There were no breakout spaces in the old school - the fact that there was often nowhere apart from cupboards for pupil-support assistants to take children with additional needs was “infamous”. Before, giving every teacher their own space and adequate preparation time was impossible, as many pupils had to eat packed lunches at their desks. This was not hygienic - with all the spillages, mess and peculiar lunchbox smells that resulted - and even if you got your head down for a bit, concentration was hard amid the crunching of carrots and crisps.

The school used to have one big hall for food, sport and drama. Now, with multiple spaces, teacher time has been freed up and there is room for bigger assemblies, as well as social events involving both pupils and parents. It has freed up time for fun but messy activities, too, - pupils can now go apple-dooking at Halloween, Kelly says.

This building also makes realising the big agendas of Scottish education more achievable, she adds. Putting herself “out there”, she would predict that, by making it easier to support all children, the new building will help to drive up attainment. And Kelly points out that the national push for more play in education is within reach when, even if “Storm Callum’s blowing a hoolie”, children have indoor areas designed for play.

The two-storey building feels like a modern university campus - or perhaps the headquarters of a Silicon Valley start-up - with its warm, neutral colour scheme, sense of openness, beanbags and high stools, as well as nooks and crannies offering escape from noisier spaces. Staff now have places to go outside the classroom and say they find it easier to collaborate with colleagues. Some people even call St John’s the “Costa school” - not because of the quality of the coffee but because it’s comfortable and inviting to spend time in.

Some classrooms exist in a state of flux. Tables are shaped like waves and operate as giant jigsaw pieces, while chairs are on wheels and fold up and down, so the layout of the room can be changed quickly by pupils; every now and again there’s an elegant little dance - at least in theory - like the spaceships manoeuvring to The Blue Danube in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Some changes are a little more faddish: not all teachers are keen on wipeable tables for writing on, although Kelly likes the principle that work is visible and that you do not have to flick through a jotter to find every last bit of learning.

Staff did rein in some of the “really, really radical” ideas of the building’s designers, says Kelly. Teachers wanted the best of both worlds, by retaining traditional, geometric classrooms but allowing movement into more flexible spaces, depending on the activity. There are sliding doors providing an outdoor route between adjoining classrooms, which encourages teachers to take children outside while also helping to overcome the age-old problem of friends being separated into different classes and rarely seeing each other.

I speak to an assortment of P7s - in a small library area with high stools, overlooking the corridor on the floor below - without staff monitoring what they say, and the children are all enthused about the new building. Tommy says that with more space “I can focus more”. Tylar likes the fact that, if you have missed school for some reason and not done your homework, you feel less self-conscious being able to go off somewhere and catch up quietly. Lola says teachers are happy for pupils to work “wherever we like” and frowns at memories of being “squished together” in the old building. “You just get more excited for school,” she says, adding: “You don’t really shut doors because it’s never noisy for very long.”

Open plan but better planned

For a child of the 1980s like me, there are echoes of the open-plan schools that were modish at the time. But Crawford McGhie, City of Edinburgh Council’s senior manager for estates and operational support, says there are two critical differences: these older buildings often failed because the acoustics were terrible, which is not a factor at St John’s. Even more importantly, the previous open-plan designs were imposed without any significant change in teaching approaches.

Kelly remembers that, because of the noise in such buildings, “you were goosed if you were doing a reading test”. Here, however, “you can bang your musical instruments” without ruining other lessons; the building has an enjoyable sense of “hubbub”, without the edginess noise carried in the old school.

And the new design has also liberated staff to run with modern teaching approaches. “It’s about a shift in pedagogy - not just a shift in furniture,” says Kelly.

Part of that is about letting go of more didactic methods and encouraging children to decide where to go and what to do, which Kelly says has helped to improve behaviour. One P3 boy is standing at a podium doing sums, because he feels more comfortable learning this way. “Before, I might’ve been given a row about that,” he says.

Kelly explains: “I have had fewer children coming my way [for behavioural issues]. The kids seem happy. There’s a sense of ownership - they don’t feel school’s being done to them.”

The students who might benefit most in the 365-pupil primary are the 90 with additional support needs (ASN). “We always struggled to find safe spaces to allow children with ASN a calming place to go - we just didn’t have anywhere to send them,” says Kelly.

The St John’s design team put ASN at the forefront and were determined to give these pupils much more control over their learning environment. They did away, for example, with large desks and chairs welded in place, in favour of a variety of seating, so that pupils can sit, stand or lie on the floor. They introduced “wobble stools” (which make it easier to move around while sitting) and sofas. Other schools that have tried out these innovations say pupils with ASN “love” them, and being at ease with their surroundings has helped to raise attainment.

At St John’s, children decide when levels of tension and anxiety are getting too much: whether to move to a desk on their own, pull down the shutter on a “space chair” (bubble-like pods that allow children to close themselves off from the world) or create their own little area to sink into a beanbag.

One P4 boy used to be a “bolter”: he would often run out of class or even try to escape the school altogether. Now, he is “so much calmer”, says Kelly, given the variety of spaces he can retreat to when he craves solitude. Helen Kane, a pupil-support assistant, says staff are less stressed, too: they have options and are not stuck in a corner when a child is getting anxious.

Diarmaid Lawlor, director of place at Architecture and Design Scotland, argues that the design of school buildings should be a top priority for children’s services, in an article published last month on the Tes website to mark 25 years since the charity Children in Scotland was founded, (see bit.ly/Lawlor). Badly designed schools can turn students off from learning and damage mental health, he writes, and young people must be encouraged to say how the spaces they learn in should be used.

St John’s Primary, it would seem, is on the right track.

Henry Hepburn is news editor for Tes Scotland. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

One council’s approach: ‘the environment is the third teacher’

Education must make room for children in the most literal sense, according to a document prepared by City of Edinburgh Council to help guide the building of new schools in the city.

Although council employees Lesley McMillan - an interior designer - and early years and childcare officer Joanna Hughes have written the paper with the early years in mind, the principles within it will also be applied to places where older children learn.

The document is called Background to New Builds 2018 and sub-headed “the environment is the third teacher” (with the parent being the first teacher and the classroom teacher the second). It states that “play is the most important focus for learning in all our early years settings”, and advises that schools should have fewer tables and chairs than has been usual, leaving space for “active learning, curiosity, enquiry and creativity”.

It also spells the end for desks and tables that are fixed in place, and encourages “dens, nooks and wigwams” to create “a comforting place if a child wants some time out”. Other suggestions include walls children can write on and “wobble stools” to help pupils who find it hard to sit still on more traditional chairs. Sliding doors that blur the divide between the indoor classroom and outdoor play areas will help to “meet the need of human beings to connect to nature”, it adds.

“Beautiful, nurturing learning environments” are not an indulgence: it stresses that well-designed schools can have “a significant impact on literacy and numeracy”.

‘No real thought has been given to how a school should be designed’

Not all modern school buildings are embraced by staff. One Scottish secondary teacher fears what their new workplace will be like:

I’m really worried about the upcoming new build for our school. There won’t be a library - because libraries are not well used and are a “waste of space”, as a member of school management put it.

Some classrooms will be joined without a dividing wall; a home economics teacher has expressed concerns that she will have to work in a room with 40 pupils, 40 cookers and two teachers shouting over each other.

Each department will have a “breakout” area in the open space between rooms. No one is quite sure what we will use this for. Art may use it to display work and English are talking about turning it into a library, but it will have soft furnishings so there is a worry it will be an area that needs supervision.

There will be no “common room” or space specifically for senior pupils and no staffroom - staff are upset about this, as there are so few opportunities to speak to colleagues.

The current canteen is too small. The new school will be designed for many more pupils but the canteen will be even smaller. One suggested solution is to feed pupils from a “burger van-style building” in the playground and keep them outside during lunchtime to ease congestion. There are also huge concerns over heat and humidity, as it appears the top floor largely comprises glass walls and a glass roof.

There is a real feeling that this school is a cookie-utter design, which might have been a very nice office complex - but that no real thought has been given to how a school should be designed or how the school day works.

Your views on the impact of school buildings

We asked Twitter users how important the design of school buildings was for learning and teaching. Here is a selection of the responses:

Hugely important. Environment influences mood/mindset. All young people deserve to learn in modern, bright, stimulating environments which reflect the diverse nature of how learning takes place in the 21st century - as opposed to the “cells and bells” model from the last. @HTrenfrew_high

Very important! @PEEK_project_ work with many schools in Glasgow and there are some amazing spaces for learning and teaching and equally some dreadful ones. Some are concrete jungles with no space for kids to play. Others have vast amounts of space but no variety. @MichaelaCPEEK

[I went to] a new school in the 80s - an experiment in open plan - [after moving] from a tiny, idyllic rural school. Horrific experience. It’s just been replaced on the same site. @somers_jane

Old buildings can just be as good as new facilities, it’s what you do in them that matters. @teresa08931402

Kirkwall Grammar [on Orkney] has fantastic facilities inside and out. The classrooms are all of a decent size that allow lots of light and air into the rooms with plenty of space for displays and showing off pupil work. One of my favourite memories is seeing the senior pupils regularly practising the fiddle/guitar etc in the atrium during free time. @heathleonard

Design should consider the school as a true community asset and ensure that the local community can access it out of hours. Can we rethink the 20ft fences round some of our campuses - let’s build links into the community and take down barriers (visible and invisible ones). @SallyAnnKelly1

My current and last schools are brand new. Social and performance areas are great. The classrooms are clean, tidy, plaster-free and functional - exactly as I would expect. A previous school had open-plan hell … @mrdissent

Open plan is utterly horrendous. The distractions are almost unbearable and frequently distract [from] learning and teaching. @LeMcL17

Not enough thought [is put into the consideration of] neurodiversity when designing schools, especially secondary. Hard surfaces, bright lighting plus crowds and noise mean classrooms, halls and common areas result in sensory overload. @MeganJFarr

[It] shouldn’t just be the design of buildings [being] considered. Children need excellent daily outdoor play opportunities in natural, affording, challenging, creative spaces. This is too often not considered whatsoever. @LynieT

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters