‘We must change the conversation about post-18 education’

Three months after Theresa May arrived at Derby College to announce a government review of post-18 education and funding, little more is known about what will emerge from it.

Chaired by Philip Augar, the former non-executive director of the Department for Education, and with Blackpool and The Fylde College principal Bev Robinson representing the college sector, the review will look at ensuring that people from disadvantaged backgrounds have equal opportunities to progress to, and succeed in, all forms of post-18 education and training.

The review will examine how disadvantaged students and learners receive maintenance support from the government, universities and colleges, and how the system can deliver the skills our country needs.

The panel will focus on choice, value for money, access and skills provision, according to Augar, who has insisted: “We begin with no preconceptions.”

The panel also includes Baroness Wolf, the Sir Roy Griffiths Professor of Public Sector Management at King’s College London. Like Robinson, she also sat on the independent panel for what became commonly known as the “Sainsbury review”, which led to the creation of T levels.

Speaking at the one of the Franklin Debates organised by the Worshipful Company of Educators and City and Guilds in April, Wolf said: “[The review] is actually at least as much about skills and people who do not go to university as it is about higher education. It is not a review of tuition fees. It is not a higher-education review. It really is a review of post-18 education funding. I think it’s an opportunity that 10 or 15 years ago nobody would have been given.”

Tes understands that the panel is still in the early stages of the process, setting out how the review will be carried out. However, there are already fears that, given the strength of the universities’ lobby and the fact that HE funding is a matter of significant public interest, the review could end up getting bogged down in university funding.

The review should be an opportunity for wholesale change across post-18 education, sector leaders believe.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says the review panel is in “listening mode”. Focusing primarily on HE would be a “missed opportunity”, he says.

The shadow of university tuition fees

Julian Gravatt, deputy chief executive of the Association of Colleges (AoC), agrees.

“There’s a high risk that the post-18 review will confine itself to university issues,” he says. “I’ve seen a sample of responses [to the government consultation ahead of the review] - from Universities UK, Russell Group, Million+ and GuildHE - and, although there are differences, they all focus on adjustments to student loans, reintroducing HE maintenance grants and avoiding anything that fundamentally changes the way the system works.”

He adds: “But it is very much a post-18 review, not an HE one, so we’ve taken the government at [its] word. We want to change the conversation about post-18 education.”

Like other organisations across the education sector, the AoC is submitting a response to the government’s consultation. Today, it is launching its own consultation document for colleges (see box, above right), exploring the changes it would like to see.

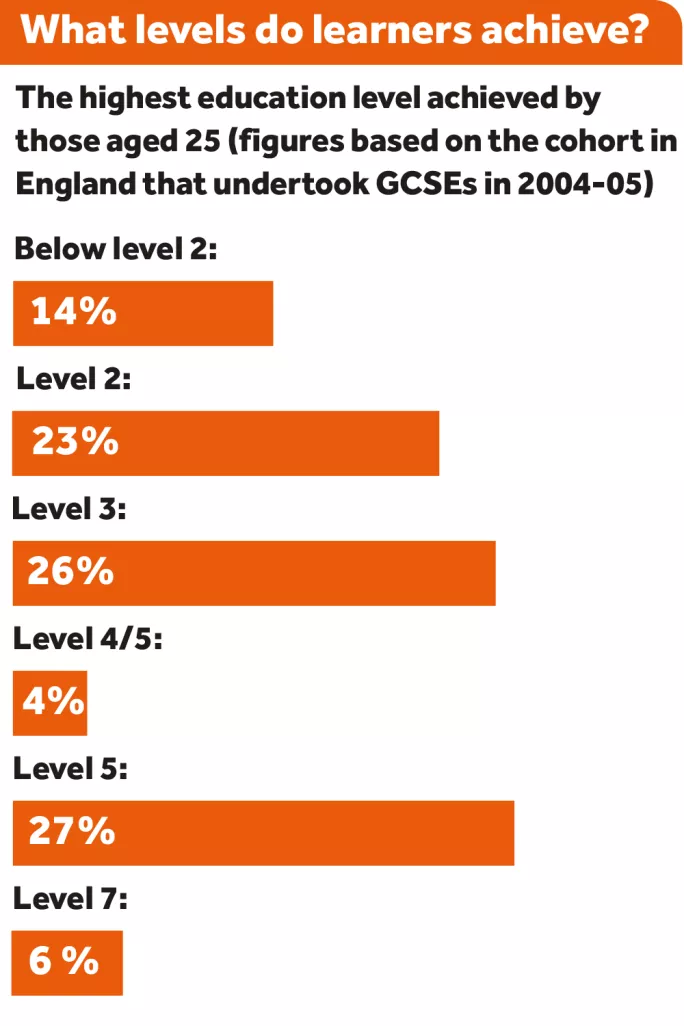

According to the latest government statistics, 37 per cent of those who sat GCSEs in 2004-05 had not achieved level 3 qualifications by the time they were 25; 14 per cent had not even achieved level 2.

“We’re not suggesting putting the money into level 2 and level 3 [per se], but into the half of the population who don’t do so well at school and who find it increasingly difficult to catch up later on,” says Gravatt. “The EU referendum drew attention to divisions that were already well known but that risk holding the country back.”

Ian Pryce, chief executive of Bedford College, says he supports the AoC’s view. “The sector needs to be challenged harder to get almost all students to level 3,” he says. “We should have a key performance measure around the number of students we get to that level, and stop using achievement rates as any sort of measure.

“Our data shows that students leaving us after level 1 have a 63 per cent chance of getting a job. After level 2 that rises to 83 per cent; after level 3, to 93 per cent; and after level 4-plus, to 98 per cent. A measure that thinks achievement rates on level 1 are very important misses the point.”

Broadening access to level 2 and 3 qualifications shouldn’t amount to less focus on high-level skills, Hillman says. Rather, this would bring more people up to a level where they are able to make use of other education opportunities. With life expectancy continuing to increase, people should spend longer in education, he adds.

Hopes that the review will do more than simply rejig funding for university courses are also high in the wider adult education sector. Sir Alan Tuckett, who spent 23 years at the helm of the adult learning body Niace (now the Learning and Work Institute), says that policy needs to be fair, equitable, affordable and flexible. “The system needs to help 18-year-olds entering the labour market, those in their twenties and thirties upgrading skills, and people looking for a career change in their forties to their late sixties. Everyone should have access to secure public support at 18 or afterwards,” he adds.

Ruth Spellman, chief executive of the Workers’ Educational Association, says the review provides a “real opportunity for change at a very crucial time for adult education”.

“We hope that the post-18 review will not end up with a narrowed focus as we need to make sure the large numbers of adults who lack skills in literacy, numeracy and digital skills have clear pathways, and issues of access and progression are addressed so that they can go on to level 2 and 3,” she adds. “We must remember the adults for which level 2 seems a million miles away, and make sure that adult learning is within reach for all.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters