This story was originally published on 7 November 2023.

What emotions have you experienced today? Irritation when someone pushed into you on the train? Panic when you realised a marking deadline was closer than you thought? Excitement and apprehension about seeing an old friend for the first time in a while?

Your emotional vocabulary allows you to describe these feelings in words. This language has been modelled and labelled for you, over many years, since the day you were born.

Just as we teach subject-specific vocabulary, we need to help children learn emotional vocabulary. This is what allows them to explain their feelings, reducing the need to use behaviours to communicate their emotions.

Read more:

Talking openly about emotions in the classroom is important for several reasons. It communicates that feelings are valid, rather than something to be shut off or ashamed of; it signals that you are interested in how your students feel, not just in their behaviour or academic work, leading to more effective adult-child relationships; and it can help to de-escalate behaviours that are difficult to manage, because you have demonstrated understanding and acceptance rather than judgement.

There’s every reason to incorporate talking about feelings in the classroom. But how can you do this well?

How can you talk about feelings in the classroom?

Teachers should not be expected to be therapists. Supporting children’s emotional development can happen through everyday conversations. Below are some ideas that you can incorporate into lessons, group work or form time:

1. Weave emotions into the curriculum

Where possible, label and name feelings as part of your teaching; this introduces emotional language into the curriculum. For example, label the competing feelings of a character in a novel or consider the emotions of people living through a particular period in history.

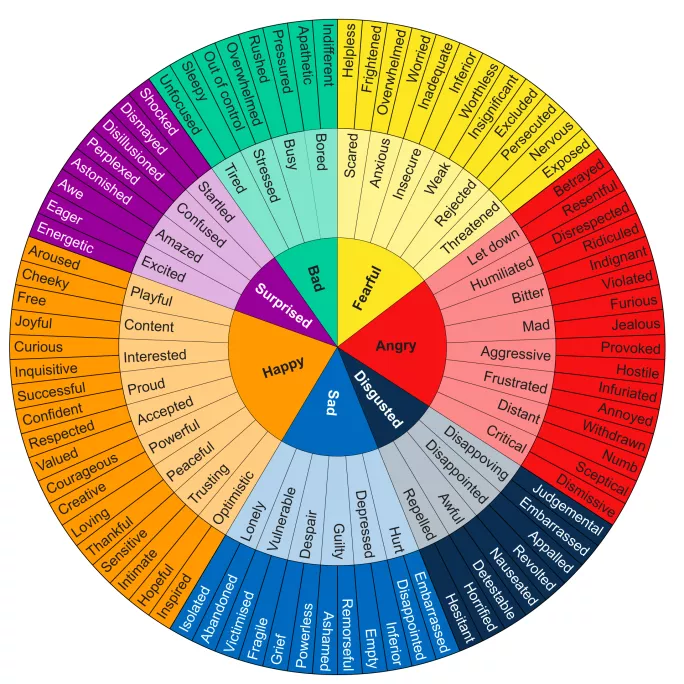

You might want to refer to an emotions wheel (see image below) to show students the range of emotional vocabulary available to them. Put a copy up in your classroom or use it with your students in tasks.

2. Call feelings out

Outside of the curriculum, don’t be afraid to talk about your own feelings (within reason!) or those of your class. You could do this by labelling the class’ apprehension about an upcoming test or describing your feelings of pride at your students’ maturity in a class debate.

You can also call out the feelings you’re noticing in the classroom. For example, if your class has returned from lunch restless and disgruntled with each other, name those feelings using age-appropriate language (“wiggly”, “bouncy”, “fed up”, etc) and problem solve with the class what they could do to get themselves ready for the afternoon.

Picture resources such as Blob Trees can help here. These can easily be found for free online. The images don’t have to be serious either - asking everyone to reflect on which of several sheep they are that day, and why, can be a great talking point (see image, below).

3. Depersonalise talking about emotions

Use current news stories or familiar scenarios with made-up characters as stimuli in conversations about emotions so that students can apply emotion words and consider different perspectives without making discussions too personal.

Structured approaches such as the Zones of Regulation - a social-emotional learning curriculum that uses the language of colours to describe feelings - can also be helpful to describe emotional states. For older children, you could get creative with other types of scales to show gradients in feelings, such as a Nando’s-style “spice level” thermometer.

It’s how we manage emotions that’s important

With all approaches, it’s crucial not to judge children for their feelings. We need to show them that all feelings are valid and accepted, but that we must learn to recognise and manage those feelings in the most helpful way.

So, if your class comes back from break in a bit of a “wiggly” mood, name that without telling them off. Children need to understand that wiggly moods are OK; it’s how we manage them that’s important.

Cathleen Halligan is an educational psychologist working for a London council